After years at the crime desk, a journalist writes his own (crimeless) story.

A large wooden board hangs on the far wall of the Times Media Limited (TML) staff canteen at the company's Port Elizabeth office. On the board, in gold lettering, are the names of staff members who have served the group for thirty years or more. Some have devoted fifty years of their lives to the various newspapers. When they retire they receive a substantial amount of money, but by then many do not walk very well, their eyesight is bad from staring for hours at computer screens, and their health is poor from breathing polluted air.

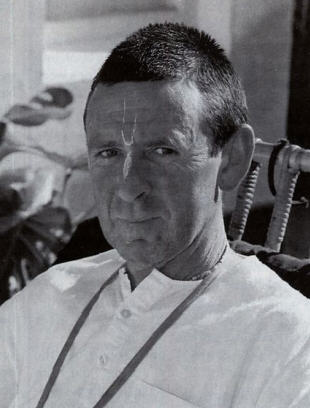

Andrew Whitlock

I looked at that board many times while munching away at a hamburger or some unidentifiable food and wondered if my name might one day be etched in gold on that shiny wooden surface. And there were times when I thought it just might, if I could survive that long on the kind of food I was eating.

That was a decade ago, and it was a time when life started taking as many twists and turns as a rattlesnake crossing a cactus-filled desert. There were signs I did not notice and some I ignored as they flashed by like train stations. I am sure you know what I mean. We all experience these moments in life, and thinking back on them we consider what might have happened if we had chosen a different road, or if we had climbed off at a particular station to see what was there, instead of taking the ride to the end of the line, unable to get out of the seat.

My work as a journalist, sub-editor, news editor, and film critic kept me busy in the material world. There were other distractions, like a live-in surfer girlfriend and my four-year-old daughter I had custody of. I tell you these things so that you can have a picture of the life of this journalist who was moving along the track of life in the material world, looking at the different stations. It would be the same for doctors, lawyers, butchers, nurses. Get up in the morning, go off to work, drop my daughter off at preschool, drive the same route most days, see the same cars, people, robots, hobos, shops, schools, churches. Park the car and walk up the steep narrow road to the back entrance of TML, the stale smell of diesel and damp paper hanging in the air.

I'd see a man who had done this for almost fifty years, parking his BMW. Sometimes as I followed him I wondered what made him walk this path for so long. What was holding him, tying him and me to this path? I see clearly now that I had these thoughts because we are spiritual beings and even in the semiconscious state we walk around in, we have flashes of spirituality.

I was wondering about God and how I could get to know Him, while I wrote stories of life and death in the city. Crime stories mainly. The tragic and bizarre Walmer murders, still unsolved, the story of Port Elizabeth's first serial killer many stories that took up a part of my life each day. The routine, material world spun around and around.

A Missed Opportunity

But there was a time, another of those spiritual moments an opportunity and even though I was an observant journalist, I admit I missed it. It was a summer's day, bright sunlight, and time for a break from the crime desk. So I took a walk down Main Street, enjoying the perfect weather. I only noticed the man when he took a step forward. I noticed that his head was shaved and he looked very healthy. He offered me a book.

"Would you like to take this? Read it. I'm sure you'll find it interesting."

I waited for him to ask me for money. I looked at the book's cover. Gold lettering that reminded me of the board in the canteen.

"Sorry I didn't bring any money," I said, as I felt around in my Levi's pockets and found a few coins.

"I've got two-rand-fifty," I said.

The book felt good in my hands, the gold lettering raised ever so slightly on the cover.

"That's fine," he said with a smile.

I was struck by how content he looked and by his pleasant manner. I thought, A bargain at last. Where can one get a book for two-rand-fifty? Even if I never read the book, I have a bargain.

I flipped through it when I was back at my desk, thinking I might find some healthy food recipe.

"Abandon all varieties of religion and just surrender unto Me. I shall deliver you from all sinful reactions. Do not fear."

That was what I read. Then the telephone rang and I popped the book into my briefcase, where it stayed for a week before I placed it on the top shelf of my bookcase. I did not read it.

Another Look

I'm looking at a copy of that book now. It is five years later, and in that time I have resigned from the Herald, moved to Johannesburg, worked for the Sunday Times, resigned from the Sunday Times, moved back to Port Elizabeth, worked as a freelance journalist, and moved to Cape Town, without knowing why. This was after reading just that one line.

Of course, I have found out the reason for all my moving. And I am pleased that I did it partly on a gut feeling, partly on faith, and partly through having no choice.

The day I saw the book again, I had awoken with a particular thought on my mind, walked to a nearby pay phone, called 1023 and gotten the number I needed. I was given an address, and I made an appointment for 10:30 A.M. I have made many appointments in the past eighteen years as a journalist, and I have never been late. This time, in what has turned out to be my own story, I was late. Instead of the place I was looking for, I found myself outside President Thabo Mbeki's residence.

"Do you know where Andrew's Road is?" I asked a policeman on gate duty. "I'm looking for the temple."

He looked at me blankly, as if he hadn't heard me. Suddenly a flash of morning sunlight twinkled on the SAP name tag Van Wyk. He shifted his weight from one foot to the other and looked thoughtfully at the driveway leading to the President's residence.

"Is that the place where those okes with the long dresses and little handbags hang around? You'll find them at the small church next to Rondebosch station."

And he was right. But I was fifteen minutes late. I felt in the pocket of my jeans, and this time I had a ten-rand note. I knew this was the last of my cash. I had closed my bank account a few weeks earlier. But somehow, since then I had managed. At the same time I had reached the end of a journey, and the beginning of one.

From my years as a journalist I knew there were many men and women who gave up hope if they lost material possessions such as their house or car or household goods. I had written stories about people who had ended their lives because of financial difficulties. So I did not understand why I felt such joy as I handed the ten-rand note to the healthy looking man with the shaved head.

I told him the story I have told you, but added a few details. I told him that I had noticed how people seem to do the same thing over and over, that there was no point to what they were doing. In the past few months I had broken some of the chains tying me to the material world. It had started when I sold my house, and now I had few possessions. I had the freedom to spend many hours walking along the beach at Sardinia Bay, listening to the sound of the waves.

The man simply agreed with what I said, as if he had known this for many years. He asked me if I would like to come to the temple the following morning. And this is where the real story begins.

The Sound of Waves

I arrived on time at 7:00 A.M. I had started reading the book the night before, and it made perfect sense. I had read many books, all kinds of books. But I had never read anything as clear as this. It was like the ringing of a giant bell. Seawater rock pools on a clear spring morning, clear like that.

Sitting at the temple with a group of chanting devotees, I was reminded of the sound of the waves. Every wave has a different voice, and in the temple, every devotee had a different chant. The sound is like bees in a hive. And when you hear this sound and become part of the sound time becomes fluid.

When I chanted the Hare Krsna maha-mantra for the first time, it seemed as if I was walking up a mountain. The second time I felt as free as a dolphin leaving the wave.

Now there is time for everything. No deadlines. There is continual learning, each bit of knowledge a tiny step closer to satisfaction, and to submission.

It is a huge change from journalist to devotee. I was fortunate in many ways because I had already broken some of the material chains on my way to beginning this spiritual journey, and there were some weak links in the other chains. So I continue on this journey that everyone should follow.

Andrew Whitlock, now a member of the ISKCON temple in Cape Town, spent eighteen years as a journalist writing for leading South African newspapers.