A family takes a pilgrimage to the land where Krsna appeared.

Completely out of season for Vrndavana, a storm announces itself with crackling lightening and booming thunder. Chilly north winds hurl bluish-black clouds across the afternoon sky. Suddenly rain pours and sends everyone running for cover. Caught far from our quarters, my wife (Jitamrta Dasi) and I duck into the secretary's office at ISKCON's Krishna-Balaram Temple. The secretary smiles and invites us to pass the time by looking at her picture book containing photos of the temple opening in 1975. The many photos of Srila Prabhupada include one of His Divine Grace leading an elephant procession from the temple the night of the opening. Among the dozens of beatific faces following him is a thin Westerner looking younger than his twenty years. It was me, on my first trip to India.

Now, twenty-five years later, on a four-month assignment elsewhere in India, my wife and I have resolved to bring our girls, Laxmi (11) and Leela (9), here to Vrndavana. Since we want to raise them as devotees of Krsna, we must do our best to introduce them to Vrndavana, the sacred village of Lord Krsna's youth. Thousands of Krsna temples grace Vrndavana. Their bells ring night and day, blending with the sounds of chanting and of catcalling peacocks to create a Krsna conscious atmosphere found nowhere else.

It's hard to believe how much Vrndavana has changed since 1975. Vrndavana then had few amenities for visitors and devotees. Srila Prabhupada's newly constructed Krishna-Balaram Temple rose high above the quiet, surrounding ashrams on their spacious lots with bird-laden trees. A rural atmosphere prevailed. Not so now. After the phenomenal international response to the Krishna-Balaram Temple, dozens of new temples and ashrams have sprung up all around this formerly serene neighborhood known as Raman Reti. Standing on the road in front of Krishna-Balaram now reminds one of Mumbai at rush hour.

Mundane vision cannot see the true Vrndavana, Lord Krsna's eternal abode. My lovely children appear to be something less than perfect and pure devotees. I wonder if their impression of Vrndavana will be caught up in the comfort of our newly built accommodations or the recently arrived Disneyesque attractions (such as thirty-foot Hanuman and Ganesa statues standing in front of one newly built temple). Or maybe they'll just remember playing with their friends Braja (10) and Pranaya (7), daughters of Sesa Dasa and Madhumati Dasi, our good friends who are graciously hosting us here.

I remember my first impressions of Vrndavana. The historic temples, the many pilgrims, and the ubiquitous calls of "Jaya Radhe!" ("All glories to Krsna's most beloved Srimati Radharani") deeply impressed me with the veracity of my newly adopted Vaisnava practices. Will Vrndavana affect my very independent-minded daughters in the same way? I have three days to show them the Vrndavana I love.

Day One

Their mother feels ill today, so I take the girls to see some of the old historic temples of Vrndavana. Five hundred years ago, Vrndavana was a tiny rural village. At that time Lord Krsna, reappearing as Lord Caitanya, dispatched the six Gosvamis, His principal disciples, to Vrndavana. They were to uncover the ancient places of Krsna's pastimes and commemorate them with magnificent temples. Just after sunrise we climb aboard a bicycle ricksha and head off to visit some of these temples.

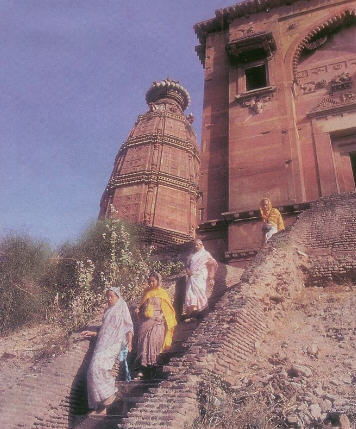

We stop first at Madana-Mohana, a beautiful temple built by Sanatana Gosvami. The intricately carved red sandstone spire stands atop a high hill, speaking the very essence of holy Vrndavana. I tell the girls how Sanatana blessed a troubled salt merchant who reciprocated by building this temple. They listen, but they are more interested in about fifty frolicking monkeys, dashing and rolling on the temple courtyard, apparently warming up for a hard day of mischief and petty thievery.

It dawns on me that it will be hard to compete with the animals for the girl's interest. Besides the monkeys famous for stealing eyeglasses from unsuspecting pilgrims and then bartering them back for food Vrndavana is full of cows, dogs, and an occasional camel. Countless pigs (Vrndavana's sanitation specialists) look plump and proud as they parade their offspring, nozzles down in Vrndavana's narrow concrete open sewers. Darting green parrots seem to merge into leafy trees. Wild peacocks strut their stuff, calling loudly and unexpectedly from trees and rooftops. The girls love it all.

"Monkey alert!" cries Leela, spotting a small pink face watching us intently from a nearby rooftop as we ricksha to the next temple. I remove my glasses and squint.

Radha-Govinda

Madana-Mohana was quiet and almost deserted, just as I remember it. But Rupa Gosvami's Radha-Govinda Temple bustles with tourists, even at this relatively early hour. About two hundred of them crowd around the altar of this large historic red sandstone temple. A pujari shows the deity and distributes caranamrta, sacred water.

I remember coming here in 1975 and exploring nooks and crannies on the second and third floors. At that time it seemed only monkeys and bats had been there for decades. Today there are pujaris and tourists and appreciation for the temple's wonderful architecture or what the Mogul tyrant Aurangzeb left of it after his seventeenth-century rampage here.

Looking up at the huge lotus-shaped carved center stone suspended thirty feet about the central gallery, the girls share my wonder about how the builders managed to raise it. It's enough to distract them from the hundreds of bats that hang all over it.

Now we head to the quiet and well-maintained Imli-tala Temple, site of a historic tamarind tree under which Lord Caitanya chanted on beads. The sacred Yamuna flows by here, not far from the temple gate. About a hundred meters across a wide sandbar we see a herd of cows and some pilgrims at the water's edge. We decide to go there for a picnic breakfast.

Breakfast with Bulls

As we cross the sandbar and find a sandy riverfront spot, I remember wonderfully purifying swims in the sacred Yamuna in 1975. But I don't mention them to the girls. Sadly, the Yamuna is now so polluted that most parents think twice about putting their offspring in her. A ritual bath of three drops on the head is equivalent to a full immersion, so we settle for that. The herd of cows, about a hundred feet upstream from us, have no such reservations. They've come from some adjacent grassy fields to drink and wade in the Yamuna's waters. The girls watch them, listening as I read from scriptures glorifying the Yamuna.

Now it's breakfast time. Before the main course a loaf of banananut bread I pull from my backpack a single large laddu from the Krishna-Balaram Temple. The moment I break the grainy sweet, a large white brahma bull catches wind of it. Immediately he turns his head from the water and begins walking quickly toward us, followed by many others.

It's hard to feel too much fear of gentle cows, but this fifteen-hundred-pound horned specimen does get my attention. By the time he reaches us, we have consumed our sweet, but this fellow is interested in the rest of the contents of our backpack. I put it and the girls behind me and step toward him with a loud "Hut! Hut!" This doesn't deter him in the slightest. He and a dozen of his multi-colored friends close in, aggressively assessing us with their black, wet noses. Standing behind me, the girls stare and hold each other.

Suddenly we hear a sharp, high-pitched "Hey!" Instantly the intruders dash off, followed quickly by another fifty or so cows, oxen, and calves in the herd. As they pass we see following them a wispy-thin boy, no more than six, carrying a stick and looking very much in charge. My charming daughters giggle at the sight of their powerful father rescued by such a lad. I smile and remember Krsna, another Vrndavana cowherd boy who has also rescued me.

Radha-Damodara

Last stop this morning is Radha-Damodara Temple. Here we find lots of action. At the front entrance pilgrims line up for free kitri (a nourishing rice, bean, and vegetable stew). Others crowd the altar for a special darsana. Workmen pound away, installing a new temple office next to the rooms where Srila Prabhupada once lived. In Prabhupada's kitchen we find a devotee distributing prasadam. In Prabhupada's bedroom two devotees chant japa. We then join other pilgrims reverentially circling many historic samadhis (shrines), including those of Rupa and Jiva Gosvamis, two of the six Gosvamis.

On the ricksha ride back to our ashram, I explain that the invading Muslims forced many of the original deities of Vrndavana to be moved to Jaipur. The Deities we've just seen are pratibhu murtis, or replacement deities with the same potency as the originals. But all this is lost on the girls, who are enamored by the sight of a camel pulling a heavy wheat-laden cart. Close up, the camel seems huge.

"He's taller than Sesa Prabhu!" declares Laxmi, citing our six-foot-tall host for comparison.

Day Two

Their mother is not yet well, so the girls and I set off with five friends for a four-hour boat journey on the Yamuna. Our boatman, Mohan Lal, is a resident of Vrndavana, an auspicious birth. I mention this to the girls. As he starts rowing, Mohan pops into his mouth some pan a mixture of betel nuts and spices wrapped in a betel leaf. The girls watch him skeptically as his lips grow red and he occasionally spits the mildly intoxicating crimson juice into the sacred river.

Mohan's simple wooden boat is spacious enough for the eight of us, and he sets up a cover to shield us from the burning sun. We leave from Keshi Ghat. Here the Yamuna flows deep and bends gracefully to the long sandstone staircase of the historic bathing ghat where Krsna killed the demon Kesi. Pilgrims stand out on the beautifully carved and domed dark-pink sandstone piers that project from the stairs into the river. Floating by, we see the spire of Madana-Mohana Temple appearing in the background. The village bustle behind us, we now hear little more than the calls of some water birds and the gentle splash of Mohan's oars. Having heard Krsna's pastimes since their days in the womb, the girls now seem caught up in the atmosphere where they took place.

Graphic Lessons

The tranquil scene is broken by the gradually increasing sound of heart-wracking wails. We see on the opposite shore a circle of women of various ages clad in bright multicolored saris. They are indeed crying. One young girl's voice penetrates the general din. "Lala, Lala," she howls, meaning "little brother." Mohan confirms that a nine-year-old village boy has died of disease and has just been cremated here. Madhumati, who is from an Indian family, explains things a little further:

"When a loved one dies," she says, "by tradition friends and family simply spend some days together crying. Everyone expresses grief, and when another friend or relative arrives, a whole new round of crying begins. During this time no one expects anything else of the family. After a few days, the tears dry up. The grief is purged and life goes on."

Shortly after seeing this, Laxmi is shaken by the sight of a human infant's corpse floating past just under the river's surface. Madhumati explains that when very young children die their bodies are not cremated but simply interred in the sacred river. I watch the girls' faces become sober. Such sights, unimaginable in the sterilized West, seem to help bring home to them practical application of the Bhagavad-gita's teachings: the body and the soul are different. The eternal soul is the real person, and once it leaves, the body is fit only for destruction.

Chapati Warrior

Now the river scene becomes idyllic, with little more to see than exotic waterfowl and fields of wheat growing right up to the river's edge. The girls relax and play with Braja and Pranaya as my friend Yaduvara reads a beautiful description of Krsna's pastimes. Another companion, Narayani Dasi, a U.S. born veteran of nearly thirty years in and around India, enthralls the girls with a tale from her early days here.

"I had come with one of the first groups of Srila Prabhupada's disciples to visit Vrndavana," she says. "We stayed in a big old palace near Keshi Ghat. One day, one of the young brahmacaris [celibate male students] in our party saw a cowherd beating a cow with a stick. It seemed too harsh to the young devotee, so he tried to stop the man, and they scuffled. Soon our quarters were surrounded by a mob of outraged villagers. My roommate Malati, expecting to die, adorned her body with large tilaka marks and marched out to confront the crowd armed only with chapatis [flatbread]. Somehow the mob accepted her gesture and dispersed."

Narayani goes on to say that in the Vrndavana of those days one rarely saw a car, what to speak of foreigners. Srila Prabhupada's efforts to convince the locals to accept his disciples eventually bore fruit, in spite of their mistakes. Today, the Vrndavana residents generally accept the international members of ISKCON as sincere devotees of Krsna.

The rest of the day passes pleasantly. We stop and wade in the shallow Yamuna, then enjoy a picnic lunch on the boat as we follow the river to Mathura. Mohan lets us off at Vishram Ghat, where Krsna rested after disposing of the evil Kamsa. We hire a taxi and return to Vrndavana. The girls are tired but report excitedly to their mother about the day's adventures.

Day Three

My wife has recovered and joins us today. We decide to hire a comfortable jeeplike Tata Sumo for our last day's pilgrimage. The cost $20 for four hours, driver included is quite low by Western standards, but equivalent to a month's income for many local people. Our time is short, so, traveling like princesses, today the girls will see Govardhana Hill.

To protect the simple villagers from King Indra's wrath, five thousand years ago Krsna lifted sacred Govardhana Hill, which lies about twenty kilometers from Vrndavana. Today it's a major place of pilgrimage for Lord Krsna's devotees. Thousands come every full-moon day to circle the hill. Many pilgrims traverse the twenty kilometers around the hill by offering their fully prostrated obeisances, standing where their hands have reached, and again prostrating fully in devotion. Ascetics sometimes move piles of 108 stones in this manner, placing one stone at the end of each outstretched prostration, and not stepping forward until the entire pile has been thus moved. Following such processes requires many weeks or months to complete a circumambulation. I point out some such devoted pilgrims to the girls as we whiz past.

Radha Kunda and Syama Kunda

We begin at Radha Kunda and Syama Kunda, two historic and extremely sacred lakes that form the "eyes" of the peacock-shaped Govardhana area. Our sixteen-year-old guide, Kesava, a bright young South African-born graduate of the ISKCON Vrndavana gurukula, directs the driver. As we negotiate the narrow streets near the kundas, a man sitting on a motorcycle spots us in his rear-view mirror as he combs his well-lubricated hair. He sports a mustache, fancy cloth, and betel-red lips. As we stop the car and step down, the large man strides up to the slight Kesava.

"Radha Kunda? Syama Kunda? Gosvami samadhis and bhajan kutirs? I will show you. Come."

"Don't talk to him!" warns Madhumati. "He just wants money."

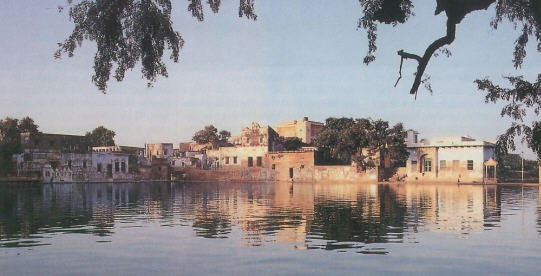

Radha Kunda and Syama Kunda

As I step out of the Sumo and gather the girls, he approaches me with the same offer. "No, thank you," I say firmly. We follow Kesava down to the nearby edge of the kunda and take three drops of the sacred water on our heads. I explain to the girls how these two lakes were dug by Radha and Krsna for each other, and how their waters contain all holy rivers. I also relate to them how Raghunatha Dasa Gosvami, one of Lord Caitanya's principal followers, excavated the kundas to their present size and then lived here chanting Hare Krsna in profound love for nearly fifty years. The girls are interested. We proceed to Raghunatha Dasa Gosvami's nearby bhajan kutir, or place of chanting. Our would-be guide follows closely behind.

Tightly packed ashrams surround both kundas, but this one is particularly sweet. Here wise and mellow-looking devotees continuously sing melodious bhajans (hymns). We circle a modest shrine to Raghunatha Dasa Gosvami and see the beautiful Deities worshiped by Jahnava Devi, the divine associate of Lord Nityananda and Lord Caitanya.

I ask Kesava to take Laxmi and me the short distance to the place where Krsnadasa Kaviraja Gosvami chronicled Lord Caitanya's life in Sri Caitanya-caritamrta. Kesava is a bit uncertain about which way to go. Before he can ask someone, our would-be guide, who has been lurking within earshot, grabs him by the arm and says, "Come," dragging him out the door. Laxmi and I have no choice but to follow.

The nearby shrine is closed.

"Come, I will show you other places," says our eager guide.

We decline and return to the rest of our group. Together we step out onto Jahnava Devi's beautiful sitting place, a twenty-foot-square stone platform raised above the kunda. It's a perfect spot to see all of Radha Kunda, yet removed from the many pilgrims on the opposite bank.

Wide-eyed, the girls take in the surroundings. Madhumati and her two daughters show them Jahnava Devi's private bathing place, steps hewed through the platform where she could descend to the kunda without being seen by anyone. The girls go carefully down the steps and touch the sacred water to their heads. Kesava describes various pastimes associated with Radha Kunda. I happily sense that the girls are now drinking in the Vrndavana atmosphere.

"Come, come! I will show you more places, better places!"

Our aspiring guide has followed us here and managed to break the spell.

"Sir," I tell him, "we know where to go. How much will you charge to just leave us alone?"

He's offended.

"You go back to Vrndavana!" he says, and stalks off.

I've been cursed in worse ways. The risk of the offense seems worth a few more minutes of commercial-free tranquillity.

We return to our car via Syama Kunda, but many other locals vie for our attention for one thing or another. It disturbs the girls, and they're eager to go. I sigh as we climb back into the Sumo, leaving behind this holiest of holy places.

Kusum Sarovara

We stop next at Kusum Sarovara, a breathtaking, picture-perfect shrine set back from the road behind a large kunda. I recall swimming here with hundreds of ISKCON brahmacaris in 1975. It's nearly deserted. Followed by their mothers, the girls run over to the inviting steps going down to the kunda and begin to play in the water. Kesava and I go to another side of the kunda to swim. Soon the ladies are calling us. Part of Leela's favorite Punjabi outfit has blown into the water. Kesava makes a valiant effort to find it, but it has sunk into the deep, murky waters. Leela is despondent.

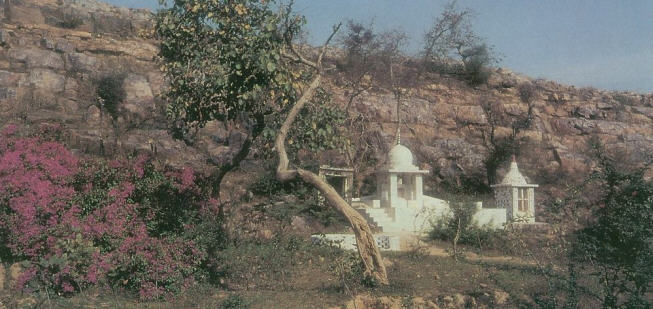

To cheer her we walk upstairs to the shrines. On this spot the cowherd maidens of Vrndavana once picked flowers for Krsna, hence the name Kusum (flower) Sarovara (lake). A Vaisnava king built the three beautiful edifices we are now seeing as memorials for himself and his queens. They are nonetheless dedicated to Radha and Krsna, whose footprints appear in the center of each shrine, surrounded by fresh flowers, a sign of daily worship.

An elderly sadhu approaches us, accompanied by a younger Indian woman in a sari. She is Palindri Devi Dasi, a South African-born ISKCON devotee residing in Scotland who is now on assignment here. She cares for the elderly sadhu and his wife. The girls listen closely as she explains their story.

The sadhu, now eighty-three, became the resident priest here when he was thirteen. He has faithfully served here all his life. He and his wife reside in a small temple next to the lake. The large deities in that temple were stolen by British as "souvenirs." Today, with Palindri's help, he and his wife worship simple Radha-Krsna deities and silas (small sacred stones) in the temple and greet visitors to Kusum Sarovara.

The sadhu is a wonderful gentleman and tells us many of Krsna's pastimes associated with the area. Madhumati and Palindri translate his Hindi descriptions. The walls and ceilings of each shrine sport faded but beautiful paintings of Krsna's pastimes. He takes us to his favorite painting, in which Krsna is braiding Radha's hair. Radha holds a mirror, but rather than looking at her hair she is looking at Krsna. Krsna looks back at Radha's eyes in the mirror instead of paying attention to braiding. We are all pleased and charmed.

ISKCON Govardhana

Feeling rejuvenated, we proceed to our next stop, ISKCON's new center at Govardhana. I've heard bits and pieces about it, but I don't know what to expect. We are all in for a pleasant surprise. The center is beautiful and the devotees gracious. The president, Gaura Narayana Dasa, tells us the building's history.

"A king in Madhya Pradesh, central India, was a great devotee of Govardhana and built this as a palace for spiritual retreats. Later his son, Maharaja Bhavani Singh, also came here occasionally but was unable to maintain it. He decided to sell the property to a spiritual organization that would use it for its original purpose. He sold it to ISKCON for a modest price, over the objections of many other prospective buyers who offered much more money but had commercial purposes in mind."

Since ISKCON acquired the property six years ago, many devotees have contributed time and money to renovate the historic structure. The entire compound, which rests on about 1.5 acres immediately adjacent to the highest point of Govardhana Hill, reflects construction and design guidelines from India's ancient Vastu scriptures. The building is an auspicious 108 by 108 feet. Its front entrance faces east, despite Govardhana Hill's being to the west. The walls are very thick two to three feet because, as Gaura Narayana explains, "Govardhana is one of the hottest inhabited places on earth."

The thick walls seem to work, for the rooms are surprisingly cool on this hot spring day. We tour the Maharaja's room, expecting something quite plush, but instead find only a small, simple suite of bedroom, sitting room, and bath. The queen's quarters are the same. On the roof we see guard rooms, now guest rooms, on each corner.

Climbing another set of stairs we reach a special bhajan kutir built for the king. Here one can sit and chant while contemplating Govardhana and the nearby Harideva Temple, where Lord Caitanya danced. Clearly the king was quite religious. The new owners are indeed using the building for its intended purpose.

The girls are impressed as Gaura Narayana shows us a collection of silas sacred stones from Govardhana in the front yard. When the devotees occupied the property, they selected one of the many silas there to worship on the main temple altar and set the rest on an outdoor altar beneath a tree. In the ensuing years, this particular tree has grown into an umbrella for the silas. It is quite unusual, be-cause the branches have grown out and down instead of up as do all the other trees in the yard.

Gaura Narayana serves us a delicious lunch, and we take his leave. Being tender-footed pilgrims, we conclude our circumambulation by car, passing thou-sands of simple and humble pilgrims walking and offering prostrated prayers to Govardhana. We chant Krsna's names as we return to the Krishna-Balaram Temple in Vrndavana.

Moving On

It's time to return to the West. Later, back in school, the girls write about their trip.

Leela writes, "Vrndavana is a beautiful village full of cows, monkeys, peacocks, parrots, hogs, people, and dogs. There are beautiful temples and lakes like Syama Kunda and Radha Kunda and Kusum Sarovara (a temple with a lake in front). It was nice in India, but it is nice to be home."

Laxmi writes, "Vrndavana is special because Krsna grew up there. I wish we could have stayed longer than just three days."

It is said that one who circumambulates Govardhana escapes the cycle of birth and death and goes back to Godhead. Similar blessings are there for those who bathe in the Yamuna or spend one night in Vrndavana. Who can predict how my children will live their lives or how deeply Vrndavana has touched them? I know only that I have done my fatherly duty by introducing them to Vrndavana. By doing so I feel I have fulfilled a duty to my spiritual father, Srila Prabhupada, who kindly introduced Vrndavana to me.

Kalakantha Dasa, author of The Song Divine (a lyrical rendition of the Bhagavad-gita), lives in Gainesville, Florida, with his wife and children. He is the resource development director for the Mayapur Project.