BIR KRSNA THE CALF loves coconut fudge, and Sita the teamstress knows it. Her pockets bulge with the sweet as she and Bir walk to the training ring. Today the calf will learn his first call: "Get up!"

Suresvara Dasa

The earth is soft from the recent rain. Sita carries a lash and leads Bir with a rope tied to a blue halter. The calf bounds through a cluster of gnats, then slows as they come to the ring. What's this?

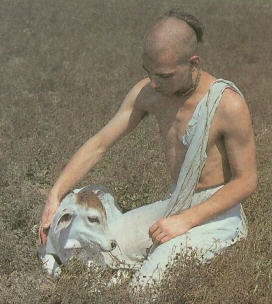

The gate opens, and Bir walks in to explore. He treads the edge and sniffs the white hardwood boards. The ring is twenty-four feet in diameter. Hoofprints stud the grass and mud, the signatures of oxen training. The calf's eyes blink and widen at his new surroundings. Sita wants to reassure her charge. She strokes his head behind the ears. "Good boy, Bir."

Time to teach the call. Sita walks to the center of the ring and lets the rope slacken. She raises the lash and taps Bir on the rump ("Get up!"), goading him forward. She follows him closely, indicating with her body he should keep going. When he stops, another tap. "Get up!"

A few times and Bir has made the connection between the tap and the call. "Good boy, Bir. Come here …" The calf walks over to Sita, who kneels and holds up a piece of fudge. A crumb falls on the kerchief crowning her hair, flaxen from the sun. A flick and a lick and Bir has it, his lotus eyes beaming. They are making a pact, animal and human, sealed in mud and trust.

At three months, Bir is the youngest calf at Gita-nagari, the Hare Krsna farm community in central Pennsylvania. Unlike his brethren in modern "factory farms," Bir will never suffer the "veal-crate fate." Every year, more than one million male calves are born into darkness, and kept there, chained round the neck in a stall so tiny they can neither stand up nor turn around. To keep their flesh pale and tender, they are denied sunlight, exercise, and even solid food. Their liquid diet of growth stimulators, antibiotics, powdered skim milk, and mold inhibitors gives them an iron deficiency that satisfies the consumer's demand for light meat, sold as "premium" or "milk-fed" veal.

After three months of living in diarrhea, at an age when they could be trained to work, they are butchered.

Bir is learning remarkably fast. Sita doesn't have to follow him so closely anymore. Just the call and a tap and he moves forward. Has he learned his lesson well enough to move without the lash?

Sita looks Bir in the eyes and raises the lash. "Bir … get up!"

The calf takes a few steps forward, then stops.

"Get up!"

A swat on the rump and off he goes at the end of the rope, now circling behind her. Out of eye contact, he starts to slow, then speeds up again at the sound of the call. Sita beams. "Broke to the word" on the first lesson! Out comes the rest of the fudge. "Good boy, Bir. Very good boy."

To the modern farmer, Sita and Bir are an anachronism, a picture in a history book. The caption reads: "Here's how our farmers used to raise bulls for work!"

But has it been a good deal, the ox for the tractor? His muscle for the engines that roar and pollute and suck up gasoline at soaring prices? His legs for the giant wheels that crush and compact? His enriching manure for chemical fertilizers that exhaust the earth and contaminate the water table? His labor for his meat, whose industry signals the decline of our health? Such is the progress of science without religion.

Factory farming finds its antithesis in the animal liberation movement. Disgusted by man's exploitative dominion over animals, many animal rights advocates hold that animals should not have to work for humans and that humans have no right to use animal products.

The genuine advocate is often a vegan. Appalled by the dairy industry's collusion with the slaughterhouse, he shuns the cow's milk as well as her meat. There is an irony here. A cow produces an average of ten times more milk than a calf can consume. To deny humanity her milk is really to deny that she is our mother. And hence the possibility that we might treat her as such.

The same with the bull. To deprive humanity of his labor is to obscure his natural relation to us as a father, who tills the ground to provide food. This is the grave error of religion without science, for as soon as man stops working the ox, he wants to kill him. It is no accident that the technology that produced the tractor also produced the slaughterhouse.

The vegan rightly challenges exploitation and murderous abuse. Yet decades, even centuries, of abuse do not preclude the possibility of kindly use. And that is what Krsna's cowherds have to offer.

In a field near Sita and Bir, Rasala Dasa, Sita's husband, works a team of oxen tedding hay. After hay is cut, it is tedded, or fluffed up, so air can circulate through it for faster drying. Frequent rains have made the cutting especially thick. The oxen pull a long-fingered device that grabs the hay and throws it up in the air. Rasala walks on their left side, calling commands so they go straight over the rows. Rasala rests the oxen periodically as the sun nears the meridian. They will finish the field before it sets.

Sure a tractor can do more more harm than good! In a couple of years Bir will join the oxen, spared the veal crate and the steer market. To work him in devotional service is to synthesize science and religion.

"The Vedic way is to farm with the ox," writes ISKCON farm historian Hare Krsna Dasi, "as humanity has done for thousands of years, and as much of the world is still doing small-scale, personal, noncapitalistic, nonexploitive farming. We don't have to ruin the world to produce food. We can live a simple, sweet agricultural life, as Krsna Himself demonstrated.

"This doesn't mean we have to be primitive, either. There is a large role for developing appropriate technology like ox-powered energy generators and methane digesters beyond strictly agricultural applications."

Granted, the golden calf of historical progress is a tough idol to topple. Yet listen to the Vedic view of the earth when Krsna visited some fifty centuries ago. "The clouds showered all the water that people needed, and the earth produced all the necessities of man in profusion. Due to its fatty milk bag and cheerful attitude, the cow used to moisten the grazing ground with milk" (Srimad-Bhagavatam 1.10.4).

"The years like great black oxen tread the world," wrote the poet W. B. Yeats, "And God the herdsman goads them on behind." Time will tell if our modern world can recover the good life Krsna gave us. But doers like Rasala and Sita can't wait for the world. Working oxen is too rewarding.

"There's a new moon coming," says Sita with a twinkle. "Get up!"

Suresvara Dasa, a disciple of Srila Prabhupada, has lived at Gita-nagari for ten years.