In British Columbia, Canada, some Hare Krishna neo-pioneers work to materialize an important aspect of Srila Prabhupada’s vision.

Vanamali seldom walks. Like most six-year-olds, she skips, spins, stoops, and joggles as she travels through her world on the trails and dirt roads of Saranagati Village in remote British Columbia. Her numerous trips, and those of others before her, have worn bare the path through the In British Columbia, Canada, some Hare Krishna neo-pioneers work to materialize an important aspect of Srila Prabhupada’s vision. by Yoginatha Dasa pine and fir forest from home to school.

Vanamali Dasis name means “servant of Krishna, who wears beautiful forest flowers.” She is a member of ISKCON’s “third generation,” children of the children of Srila Prabhupada’s disciples. She was born at home in Saranagati Village and is now being schooled there. The imprints of the devotees living here have formed the path she usesshortcuts between houses, from houses to the temple, and to other special places in the forest like “the red bridge.”

Twenty years ago there were no trails. The valley now known as Saranagati was once a summer hunting ground for native Indians. In the 1930s Chinese immigrants tried to raise cabbages and potatoes there. Then, in 1987, fueled by a passion to fulfill Srila Prabhupada’s desire for varnasrama, a group of devotees from Vancouver pooled their money and made a down payment on the land.

There were no homes, and there was no running water or electricity. There were a few deeply rutted roads, some broken gray fences from another age, and two thousand acres of raw, slightly rocky, alkaline landscape surrounded by trees. There was no good reason to think this land could support a varnasrama village. In fact, there was no known history of human settlement on the land. Yet it was here that neo-pioneers like Vanamalis grandparents, citing slogans of self-sufficiency and simple living, decided to build our model community.

Unlike European pilgrims who reached their New World armed with physical fortitude and basic survival skills, the only skill I could bring from my childhood in the suburbs of Seattle and two years of college was how to strike a match. In 1987, abandoning all logic and common sense, I and others equally unprepared filled pick-up trucks with a few hand tools, some secondhand windows, and miscellaneous other implements. We then ventured blindly, foolishly, and enthusiastically into the cold and barren northland known now as Saranagati, burning with enthusiasm to serve our guru and his movement.

Prabhupada’s Vision

Before his passing, Srila Prabhupada spoke often about varnasrama-dharma, the Vedic social system designed to help everyone make gradual spiritual progress. It was clearly a spoke in the wheel of his missionary scheme.

“Our duty is that we shall arrange the external affairs also so nicely that one day they will come to the spiritual platform very easily, paving the way. . . . Vaisnava is not so easy. The varnasrama-dharma should be established to become a Vaisnava. It is not so easy to become Vaisnava. (Srila Prabhupada, Mayapur, India, 2/14/77)

Although none of us could precisely describe a “varnasrama community,” we felt certain of this: A band of well-intentioned devotees with a mandate to be Krishna conscious turned loose in the British Columbia wilderness, with private ownership of their homes and a share of the surrounding land, would in time manifest varnasrama. It was similar to tossing a handful of corn seeds into an abandoned, uncultivated field in the spring and returning in the fall hoping to collect a harvesta useless technique I once tried.

What did happen?

Carrying five-gallon buckets of water down sloping icy driveways was a little disheartening after a lifetime of turning on faucets. Lying on your back in cold mud to fasten heavy metal chains onto the wheels of a truck stuck in a gooey road seemed more like stupid living than simple living. Clawing in the dirt to produce a few carrots and potatoes rather than going to the grocery store seemed like a waste of time. And spending a day in the forest cutting and loading firewood was so much harder on the back than flicking a thermostat.

I can still taste the sorry disappointment of planting my first spinach crop by squishing the seeds four inches into the soilnot knowing that I was sending them to a world of eternal darkness.

Despite these and countless other struggles, Saranagati still exists.

Was there a miraculous transformation of the landscape? By perseverance and the grace of God did the devotees turn a desert into Indraprastha, a heaven-on-earth, a glorious victory against all odds? Not exactly. We did establish gardens, a school, a temple, and twentyfive houses, ranging from rustic to elegant. And the happiness of our new life in the mountains somehow managed to win our hearts.

There is a primal satisfaction in being able to open your front door any time of the day or night and shout, “Jaya Radhe-Syama!” as loud as you wish without fear of censure from neighbors.

It is a relief to know that commuting to work means walking to the raspberry patch. Sleeping in rhythm with the seasons instead of the clock just seems right. Crystal-clear night skies with stars that blaze soothe the mind. The sprightly singing of birds has replaced the deafening groan of a giant urban machine.

These little pleasures made the burdens of “living without” seem trivial. But what about our original mandate? What about our mission? Have we established varnasrama? Have we come any closer to understanding what it is? Have we satisfied the desires of our Guru Maharaja?

A Symbolic Past

If varnasrama requires kings and brahmanas and is supposed to funnel grhasthas into the renounced order, then we have failed. And if varnasrama is meant to be a recreation of an ancient social system with well-ordered divisions of work, then again we have failed. On the other hand, if the spirit of varnasrama is to create a simple, unadorned way of life that supports God consciousness rather than constantly challenging it; and if varnasrama is intended to offer a stable, secure, and unhurried environment, a place where, as Bhaktivinoda Thakura puts it, “spiritual life can be executed easily and automatically” (Kalpataru, Song 13), then Vanamalis trail and the twenty-first-century village of Saranagati deserve a second look.

A well-worn path trod by three generations of the same devotee family certainly symbolizes stability. We don’t yet know if Vanamali and her playmates will live up to the prophecy of being the first true Western Vaisnavas, but at least we have planted the seeds, and they have sprouted.

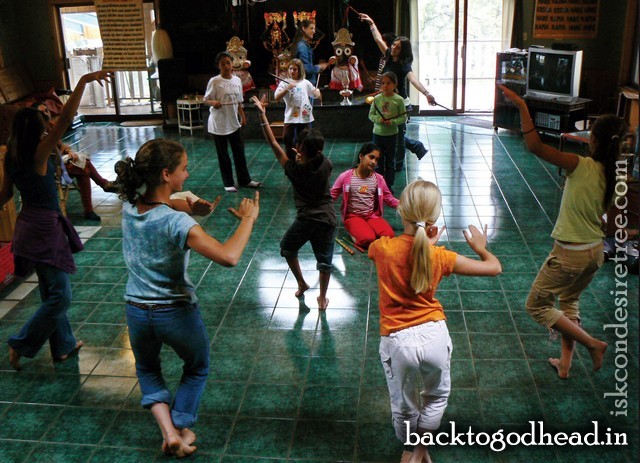

These children have not been tossed in the uncultivated fields of an impersonal institution or squished deep into the soil of gross materialism and electronic diversion. They are growing in the fertile land of Saranagati, where they can run free and breathe the fresh air. Here they come home to garden vegetables and kirtana. Their neighbors all wear tilaka and neck beads.

Time will tell if this is in fact the beginning of varnasrama as Srila Prabhupada desired it. Today, Saranagati is a wonderful place to pursue the inner life of Krishna consciousness. And if nothing else, if one day Vanamalis children joyfully walk their mother’s trail, then a rare and precious forest flower may have indeed sprouted from the rocky Saranagati soil.

Yoginatha Dasa, his wife Udarakirti Devi Dasi, and their three daughters live in a house made of straw, sticks, and stones in Saranagati Village, where they have successfully survived the Canadian winters since 1991.