A skeptical friend challenges a devotee’s faith after the devotee’s painful injury.

I recently came across a Gallup poll, conducted in 2011, in which Americans were asked, “Do you still believe in God?” Ninety percent answered yes.

The poll reminded me of an exchange I had with a college friend that same year.

“Do you still believe in God when He didn’t – or couldn’t – protect you in His own temple?”

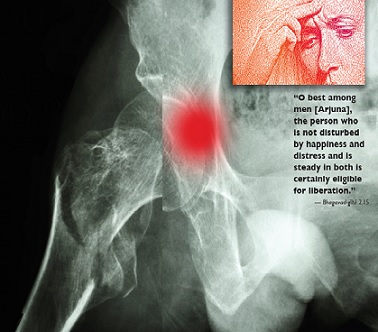

This blunt question in my friend’s email brought a smile to my face. Some months before, I had slipped on some spilled water in the ISKCON temple at Juhu, Mumbai. The fall was minor, but the pain was severe. An x-ray showed a cervical hip fracture that had dislocated the bone at its neck.

I was rushed to the devotee-run Bhaktivedanta Hospital in Mumbai, where the orthopedic surgeon Giriraja Dasa (Dr. Girish Rathore) performed a 4.5-hour surgery and advised a three-month rest for healing.

When a former college roommate came to know about the fracture, he wrote offering his good wishes for a speedy recovery. After a couple of email exchanges, he asked his blunt question. I knew he had a good heart, but he had always found it hard to understand why I had thrown away a bright career to become – of all things – a monk (brahmacari). His question about my continued belief in God had reminded me of his loving exasperation with my life’s choice and so had brought a smile to my face.

After due prayerful contemplation, I replied to him as follows:

Dear . . . ,

Thank you for your email with your candid question. I am sure several of my acquaintances had this question, but you alone had the forthrightness to raise it upfront, and so I appreciate your candor.

In reciprocation, I will give you my frank answer: a resounding “Yes.” Not only do I continue to believe in God, but this accident has increased my faith in Him enormously. Let me explain why.

To start off, I would like to remind you of an incident when we were staying in the same hostel room during our first year in college, in 1993. One night I was gripped by an agonizing pain in the abdominal area. I couldn’t reach a doctor till the next morning due to a variety of factors: it was a Sunday night, there had been a public strike the previous day, and we didn’t know what to do, as we were away from home in a new place where we had just arrived a few days earlier. As I lay moaning in pain throughout the night, you tried your best to help me. But little could be done till the next morning, when a doctor dealt with the kidney stone that had been piercing – “biting” would be a better word – me from within.

A Self-Conscious Tolerance Strategy

My recent fall was much more painful. But my suffering was much less. Here’s why.

When I fell I instinctively tried to remember Krishna – not out of devotion, but as a subconscious tolerance strategy. Since my college days, I had read many self-help books and was struck by one consistent theme in them: the enormous role of the mind in shaping our perceptions. Life presents problems to all of us, but we – or rather our mind – determine their sizes. When we let our mind dwell on a problem for too long, we blow it out of proportion and increase our misery many times over. If we take our mind off the problem whenever we are not doing something specific to deal with it, we can prevent the problem – no matter how big – from overwhelming us, and can go on with other aspects of our life.

I had found this strategy to deal with the mind’s influence highly sensible – and extremely impractical. It seemed that problems had powerful inbuilt glues that enabled them to stick to the mind. Despite knowing that I was wasting my time and mental energy fretting over an unsolvable problem, I had often found myself utterly unable to take my mind off the problem.

It was only when I started practicing Krishna consciousness that I discovered the practical means to counter the adhesive power of problems. The first and foremost principle of Krishna consciousness, as suggested in the name itself, is to be always conscious of Krishna , for this increases our desire and devotion for Him, as stated in the Bhagavadgita (12.9).

A fringe benefit of keeping our mind on Krishna is that it no longer dwells on problems. Over the fifteen years that I have been practicing Krishna consciousness, I have repeatedly experienced that irritating or painful situations become less troublesome when the mind is taken off the disturbing stimuli and fixed on Krishna . Consequently, I have tried to cultivate the habit of calling out Krishna ’s names whenever I have to do something not so pleasant, be it routine, like a coldwater bath on a frigid morning, or occasional, like a medicinal injection in a sensitive body part.

Suffering Happily

On that fateful morning, as soon as I fell I started feeling excruciating pain, like no other pain I had felt before. It seemed as if a live electric current was shooting up and down my thigh with no sign of abating. After several awfully long minutes and a few desperate prayers, I got the idea from within to start reciting verses from the Bhagavad-gita. Within moments, as if by magic, I found my mind getting absorbed; a calming, comforting sense of relief started sweeping over me. For the next several hours as I was taken first to the x-ray clinic, then to the hospital, to the CT scan center, and to the hospital bed, I was almost continuously reciting verses from the Gita. Thanks to the many opportunities to study, speak, and write about the Gita that Krishna had presented me, most of its verses were a quick recall away. As I remembered and recited the verses, I found myself relishing one of the most sublime experiences of my life. I had just recently taught the full Bhagavad-gita to a group of devotees, and our many discussions based on the commentaries of various acaryas, especially Srila Prabhupada and Visvanatha Cakravarti Thakura, were fresh in my mind, enhancing my absorption in the Gita verses.

I have often found contemplating the Gita absorbing, but this time, in great pain, the absorption was unparalleled. The main reason for the absorption obviously was not devotion, but necessity. Letting the mind wander away from the Gita verses meant that it would by default go to the hip pain, which was intolerable.

When the doctor at the hospital saw my x-ray and then saw me, he remarked in surprise, “Normally a patient with a fracture like this is never as calm as you are; he is crying in pain.”

When I reflect on that remark, I know that I too would have been crying in pain, as I indeed had been several years ago on that frightful night in the hostel. But thankfully in the interim period I had discovered Krishna consciousness.

I remembered an incident in which my spiritual master, His Holiness Radhanath Swami, had asked an ailing godbrother, “How are you?” When he candidly answered, “Suffering,” my spiritual master replied, “Suffer happily.”

When I had heard of this incident, I had thought of “suffer happily” as delightful wordplay, but now I had a glimpse of the words’ profound import: even when our body is suffering, we can still be happy by cultivating Krishna consciousness.

From Cricket to Krishna

In the months since the fracture, I have been analyzing that extraordinary experience of pain relief. Was the relief due specifically to Krishna consciousness? Or was it merely due to mental absorption – irrespective of the object of absorption? If I had been a cricket lover, could I have tolerated the pain by absorbing myself in cricket thoughts?

For a decade before I was introduced to Krishna consciousness, I was a passionate cricket lover; I could effortlessly rattle off the names of not just the players of all the cricket-playing countries, but also the detailed statistics of their stellar performances. From my own experience I can say that absorption of any kind can offer relief; I vaguely recollect seeking relief by mentally going over cherished cricket memories and fantasies while lying in pain on the night of the kidney stone. But experience testifies for me that the relief from Krishna consciousness is substantially greater. Moreover, Krishna absorption differs from mundane absorption in two fundamental ways.

1. It is independent of externals: Any mundane absorption has nothing to do with my essential being, the real “me.” The real me, the Bhagavad-gita (2.13) explains, is a soul. When I as the soul seek happiness by absorption in cricket, I do so by a chain of misidentifications with temporary externals: I, the soul, identify first with the material body that I presently have, then with the country in which that body has been circumstantially born, and then with the game that is currently popular in that country. As these externals keep changing unpredictably and uncontrollably, so does my happiness. If India wins, I rejoice; if India loses, I lament. But when I seek happiness by absorption in Krishna , I am re-identifying myself as what I am eternally: a beloved part of the all-loving Lord, Sri Krishna . That’s why happiness through Krishna absorption remains accessible amidst all externals, even if India loses and even if the body breaks. The Srimad-Bhagavatam (3.25.23) describes the transcendental, matter-independent nature of divine absorption: “The devotees do not suffer from material miseries because they are always filled with divine thoughts.”

2. It is enhanced by Krishna ’s reciprocation: Absorption in Krishna is not only real, but also reciprocal. Krishna is a living, loving person, who graciously reciprocates with our attempts to think of Him. In stark contrast, if we think of cricket it can’t reciprocate. Even if we think of not the general game of cricket but the specific cricketers, they, being limited persons like the rest of us, can’t reciprocate in the way Krishna can.

Krishna describes in the Gita (18.58) how He reciprocates with those who think of Him: “If you become conscious of Me, you will pass over all obstacles by My grace.” This verse had become a living reality, thanks to the accident; I had passed over the obstacle of the intolerable pain with the divine grace of absorption in Krishna . I know from experience that this divine absorption is not automatic or mechanical; it is a gift of Krishna ’s grace. I have recited the verses from the Gita before and after the accident, and though I generally find such recitation relishable, I have rarely been able to replicate the sublimity of the absorption during the post-fracture period.

The Protective Value of Pain

Now, coming to your insinuation that Krishna didn’t protect me, my response is that He did protect me. First, He protected me from the intensity of the pain by giving me His remembrance. Second, He protected me from the complications that could have resulted from the fracture by arranging to send me to a state-of-the-art devoteerun hospital for treatment by a caring and competent doctor who is a devotee of Krishna . Third, and most important, He protected me from the painful illusion that life in the world can be peaceful and joyful.

You will probably be surprised with my use of the words “painful illusion.” Let me explain with the example of a medical disorder called Congenital Insensitivity to Pain with Anhidrosis (CIPA). Children with CIPA feel no pain, nor do they sweat or shed tears. They are highly vulnerable to injuring themselves in ways that ordinarily would be prevented by feeling pain. Often they have eye-related problems, like infection due to having unfeelingly rubbed the eyes too hard or too frequently or having scratched them during sleep. CIPA children often play recklessly, being unafraid of banging into anything. From a child’s perspective, obliviousness to pain may seem a blessing that grants fearlessness. But from a mature parental perspective, that same obliviousness to pain is seen as a curse that impels foolhardiness. Parents of a CIPA child often have one prayer: let our child feel pain.

Just as intellectual maturity helps the parents understand the protective value of pain in this particular case, spiritual maturity helps us grasp the protective value of pain in general. Unfortunately, we are kept spiritually immature by our present materialistic culture, which by its incessant promises of worldly pleasures makes us forget or neglect the unpalatable yet undeniable signs of suffering that surround us: acquaintances get agonizing cancers, energetic people get mortifyingly immobilized by old age, thousands are instantaneously wiped out by a sudden tsunami. Thus, we unwittingly become like the CIPA patients, recklessly playing our corporate and family games, oblivious to the dangers that may befall us at any moment. And when the dangers come – as they inevitably will, sooner or later – we often resent having been unfairly singled out by misfortune. But everybody will be singled out. Though the specifics of how different people suffer vary according to individual past karma, the universal fact is that everyone has to suffer the inescapable onslaught of old age, disease, and death. Serious contemplation on these miseries, the Bhagavadgita (13.9) informs us, begins our spiritual maturation.

By spiritual maturity we gain the understanding that the sufferings of this world:

a. Protect us from the futile and fatal illusion that we as eternal beings can be happy in a temporary setting.

b. Provoke us to redirect our desires to the spiritual level, where we can reclaim the eternal happiness that Krishna wants us to relish.

I chose to redirect my desires about fifteen years ago when I made cultivating Krishna consciousness my life’s primary focus. For me, the recent accident – with its physical pain and spiritual relief – served as a definite vindication of my choice. Of course, the accident also showed me that I still have a long way to go in redirecting my desires; during the aftermath of the accident, I chanted not out of devotion, but out of necessity. Still, Krishna implies in the Gita (7.16) that necessity is often the mother of devotion. I hope and pray that in the future a day will come when I will chant the verses of the Gita with devotion. I feel confident that such a day will surely come if I diligently keep cultivating my absorption in Krishna . But till that day, I am happy and grateful to seek relief in Krishna memories – and not cricket memories.

Material pains are inevitable for all of us, and we usually either complain publicly or suffer privately. Why not explore another option, offered by spiritual growth: joyful transcendence of the pain?

Your loving friend in the service of Lord Krishna , Chaitanya Charan das

Caitanya Carana Dasa is a disciple of His Holiness Radhanath Swami. He holds a degree in electronic and telecommunications engineering and serves full time at ISKCON Pune. He is the author of eleven books. To read his other articles or to receive his daily reflection on the Bhagavadgita, “Gita-daily,” visit thespiritual scientist.com.