"I learned self-discipline and a reverence for duty, honor, and country.

But I had an itch for a more basic constitutional right…"

I first met Hare Krsna devotees in the fall of 1969, during my first year at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs. Some classmates and I were enjoying a rare weekend away from the Academy when we saw a group of devotees chanting in downtown Denver. The men's shaven heads, the flowing Indian robes, the unusual rhythmic drum beat, and the unfamiliar chant took us by surprise. "Maybe they're from another planet," we joked. We concluded they must be hippies, and we wanted to talk with them. Despite six months of military indoctrination and despite the sharp dichotomy between the military and the hip culture, we still held our old ideals and the ideals of our civilian contemporaries.

"Are you guys stoned?" I asked one of them. "Stoned?" he replied. "I gave up drugs a long time ago. Drugs are artificial. Once you've experienced the pleasure of Krsna consciousness, you don't need drugs."

His answer surprised us. We thought all young people took drugs. We were even a little envious of those who could enjoy a life of unrestricted merrymaking while we slaved through a year of rigid discipline upperclassmen screaming at us at every turn, relentless drill instructors, predawn runs with rifles. We yearned for a life without rules and regulations. Though we had voluntarily accepted the rigors of life at the Academy, we still felt some attraction for the intoxicated bliss of the hippies. But this Hare Krsna devotee was saying that he had already been through all that and was now experiencing a pleasure that far surpassed drug-induced ecstasy. That might be true, I thought, but it's hard enough being a social outcast with short hair. How could I think of becoming a Hare Krsna with no hair at all!

My conservative upbringing forced me to reject the Hare Krsna devotees as eccentric and radical. I took their Back to Godhead magazine, but it seemed too strange. I never read it.

I was raised by devout Catholic parents in a small town in a part of Vermont called the Northeast Kingdom. I imbibed the traditional American middle-class values and wanted to be a success.

As I grew older my idea of success changed. In grade school I liked being an altar boy and thought of becoming a priest. Despite attending a Catholic high school, however, my aspiration for a religious life faded. It was the late sixties, and I was influenced by the countercultural ideas of the hippies. But my desire for success was strong, and I began to think of going to college and entering the professional world.

After graduating from high school, I entered the Air Force Academy. Life at the Academy was demanding. We were training to become "whole men," ready to meet the challenge of preserving peace in our volatile times. We were learning self-discipline and a reverence for duty, honor, and country. But I had an itch for a more basic constitutional right: liberty. I wanted to be free to do my own thing. But I also equated freedom with financial security and decided to remain at the Academy, inspired by the financial rewards that would come after graduation.

By the time I graduated from the Academy, however, I had begun to wonder just what kind of success I wanted. The Academy had provided plenty of opportunity. I had set and achieved many goals. I wasn't an underachiever. But I doubted the ultimate value of all my goals and accomplishments.

On graduating from the Academy in June of 1973, I was commissioned a second lieutenant and assigned to an Air Force base in Sacramento as a civil engineer. I worked in an office with fifteen civilian military engineers, some of whom had been there for twenty years. I soon realized I didn't want to end up like them. I heard their conversations and thought how empty their lives must be. And I was following the same path. Why should I work so hard just to come to this more work, more bills, more family problems? And the senseless habits, like smoking, drinking, and watching television for hours. None of my coworkers were happy. When they arrived in the morning, I could see it in their faces. I could see it at the end of the day as they stood holding their coats, waiting impatiently for the bell to release them from their drudgery.

And these were the higher echelons, the white-collar workers with their airs of success and security. "But they're suffering as much as anyone else," I thought, "and I don't want to end up like them."

I began to think more seriously about life. I remembered moments of philosophical questioning in the past. In high school I would sometimes challenge the Sisters teaching the daily religion class. I was often dissatisfied with their answers. They would say it was a matter of faith, but I wasn't convinced of the reasonableness of that faith. I read Edith Hamilton's Greek Mythology in my senior year and thought it was just as believable as the Catholic doctrines. I thought there must be more to religion than mere faith.

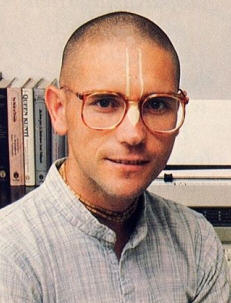

Nagaraja Dasa

At the Air Force Academy, a full academic load, combined with the rigors of military training and extracurricular activities, had left little time for philosophical introspection. Nor was liberal thinking encouraged at the Academy. After all, they wanted officers, soldiers, not philosophers.

As an engineer, I found that the relative freedom of my nine-to-five job gave me more time to think about the meaning of life. I was still looking for answers, though I noticed that most people had stopped asking questions. They had concluded, probably out of frustration, that no one knew more than anyone else, that everyone was guessing. But I was determined not to live in ignorance.

I began reading many books that dealt with the problems of human existence: Who are we? Where do we come from? Why are we suffering? Is there a God? I had already abandoned most of the religious beliefs I had held in childhood. I wasn't even sure God existed. I tended to believe He didn't, and most of the books I read reinforced that belief. I'd had my fill of religious dogma. I now favored the secular Western philosophers, who rejected God, and the Eastern mystics, who concluded that everything was God. In my speculative quest I reached a tentative conclusion: Everything is relative. There is no right or wrong, no absolute morality. Everyone is right, because everyone is acting according to his own nature.

I wanted the freedom to act according to my nature. Armed with my philosophical convictions, I went to the personnel office on the base and asked for a discharge. The lady at the desk replied frankly, "You're an Air Force Academy graduate. You have a five-year commitment to the Air Force. There's no way you can get out early except desertion." Well, I thought, maybe everything isn't relative. I realized then that even though I could say that everything is absurd or relative or meaningless, I couldn't base my life on such a philosophy. It simply was not practical.

I was also beginning to feel uncomfortable with my life and my cynical philosophy. Though I was ostensibly searching for the truth, I was still attached to petty mundane habits like smoking and drinking. I didn't like depending on those substances for pleasure.

I kept trying to find life's meaning reading, writing, and, at times, out of desperation (and despite my agnostic tendencies), praying. I should have been satisfied with my college degree, promising career, apartment, sports car, stereo, girlfriend but I wasn't. I felt an unfulfilled need to know the truth of life.

Then one sunny June day in Sacramento, in 1974, I was browsing in a flea market when a young lady handed me a book titled Krsna, the Reservoir of Pleasure. That evening as I began to read it, I remembered the Hare Krsna devotees I had seen chanting on the sidewalk some four and a half years earlier in Denver. Maybe I'll find out why they don't need drugs, I thought. To my great pleasure I found much more. I found convincing answers to philosophical problems I had wrestled with for years. I wanted to learn more.

The next day I drove eighty miles to the Hare Krsna temple in San Francisco. I told the young lady at the door that I had received one of their books and wanted to hear more about Krsna. "Oh, a pure soul," she said. "Please come in."

I thought that was an odd statement. A pure soul? I'd just put out a cigarette on the temple steps. My hostess explained that serious inquiry about God is rare. When God sees such sincerity in a person, He reveals Himself. She had called me a pure soul because of my desire to learn about Krsna.

I spoke with the devotees for several hours that day and attended the Sunday festival. I had never before encountered such a satisfying philosophy. It seemed to connect the loose ends of the various philosophies I had sampled. It answered questions I had carried with me since my high school religion class. It even awakened and strengthened the faith in God I had imbibed in childhood.

Krsna consciousness was also practical. That was shown by the devotees themselves. They weren't frustrated cynics jeopardizing their philosophical convictions by living in an absurd world. They were happy people, living with joy and enthusiasm in a world they knew be longed to Krsna. Their lives were meaningful because everything they did was connected to the Absolute Truth, Krsna, who gives meaning to everything.

While speaking with the devotees, I felt sure that Krsna consciousness was the truth for which I had been searching. Real success, I thought, is to become a pure devotee of God. But I doubted that I could live like the devotees rising early, following strict religious principles, renouncing materialistic endeavors. Their lives seemed too austere.

I knew, however, that I had to try. The philosophy seemed so right. As I got into my car to drive back to Sacramento, I instinctively reached for a cigarette. "All right," I said to myself, "but this is your last one."

Within a week I had turned my small apartment in the officers' quarters into a temple, where I followed a morning schedule of reading, chanting, and meditating similar to the devotees' morning devotional program in San Francisco. I began chanting sixteen rounds of the Hare Krsna mantra on beads daily and following the four regulative principles given in the Vedic scriptures: no meat-eating, no illicit sex, no intoxication, no gambling. I found that the self-discipline I'd learned at the Academy helped. I accepted the challenge of Krsna consciousness with the kind of vigor with which I used to attack an obstacle course.

The thrill of becoming a devotee, however, was my greatest source of inspiration. I began to experience, as the devotees had said I would, that living as a devotee of Krsna is not dry or difficult. It is a joyful life. As I began to practice Krsna consciousness, I felt a satisfaction that had eluded me throughout my years of material achievements.

I spent the next six months on the base during the week and at the temple on weekends studying the many books of His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. I learned that I could practice Krsna consciousness while remaining in the Air Force. But as I studied I became convinced that I wanted to live with the devotees and assist them in their mission of distributing the knowledge of Krsna consciousness to others. By giving Americans Krsna consciousness, I could serve my country better than I ever could as an Air Force officer.

When, in an irresponsible way, I had previously tried to get out of the Air Force, my request had been denied. When I decided to dedicate my life to serving Krsna, however, Krsna made all the arrangements, and in January of 1975 I was awarded an honorable discharge. As I drove off the base and headed for San Francisco, I felt free free to live and serve with the devotees of Krsna.