The U.S. Army is repainting tens of thousands of pieces of field equipment with a new, three-color camouflage design, replacing the standard, four-color design in use since the mid-seventies. Thousands of construction machines, such as road graders and earth scrapers, have been painted already, at a cost of about $300 per vehicle, and major weapons. such as the M-1 tank and the Bradley armored personnel carrier, are next in line.

Stuart A. Kilpatrick, director of the Army's Combined Arms Support Laboratory at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, says there are two primary methods of camouflage. The four-color method makes the painted object blend with its background, while the three-color method obscures the shape of an object viewed from more than three hundred yards away.

So what's the big difference? Considering that radar, heat sensors, night vision devices, and a variety of battlefield conditions can eliminate the subtle advantages of any camouflage design, why spend millions for the changeover?

Well, there are a couple of reasons. First of all, although both the three- and the four-color designs are well suited to the terrain in Central Europe. where the U.S. Army maintains a lot of its equipment, the four-color sometimes has to be changed to match seasonal environments there, whereas the three-color can remain the same year round. But more significantly, the changeover will allow the Army to use a new polyurethane paint known as CARC (Chemical Agent Resistant Coating), which resists chemical warfare agents better than the enamel paint used in the four-color scheme. With CARC, the Army will be prepared for the worst if the enemy decides to use nerve gas, we can rest easy that the military vehicles' paint jobs won't be ruined.

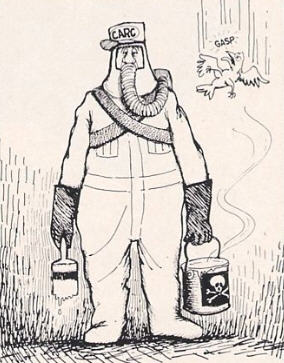

But there is a catch. CARC contains hexamethyl di-isocyanate, a chemical cousin of methyl isocyanate, the deadly gas that leaked from the Union Carbide plant in Bhopal, India, last December, killing more than two thousand people and injuring some twenty thousand more. So painters using CARC have to wear respirators and airtight suits, and they must remain under constant medical surveillance. And that's only the paint. Just imagine the "medical surveillance" that will be necessary if some of the stuff that CARC's supposed to resist "leaks" into Central Europe.

Union Carbide and the U.S. Army are among the organizations at the forefront of this century's technological revolution leaders in the development, testing, and application of the latest hardware produced by the world's best scientific minds. Their example demonstrates that, on the whole, modern science has contributed more to accelerating death than to prolonging or improving life.

Sure, methyl isocyanate helps us eliminate lots of pesky insects, but even if we write off Bhopal as a freak accident and painter asphyxiation as an occupational hazard, can we honestly believe that the widespread use of lethal chemicals won't have a detrimental effect on the environment and on our health? According to the British relief agency Oxfam, in 1982 alone pesticides caused 10,000 deaths and 375,000 poisonings in developing nations enough to make Bhopal appear small-time. And if those statistics don't convince us that the development of deadly chemicals is more trouble than it's worth, then we might try guessing how many tons of methyl isocyanate, or of its "cousins," are now stockpiled in superpower arsenals.

The Vedic literature informs us that human life is meant for spiritual advancement, which is the proven way not only to raise the quality of our lives but to eliminate death altogether. The Bhagavad-gita states that by practicing the spiritual science of bhakti-yoga, many, many people have surpassed death and have attained eternal life. After passing away from their physical bodies, they never took birth again in this world, where death conquers everyone.

Conversely, the Srimad-Bhagavatam warns us that material, or technological, advancement is inevitably accompanied by perils that always counterbalance, and usually outweigh, its advantages. For example, material science has brought us to the point where we can prolong a man's life for a few months or years by installing a plastic heart, but that can cost millions of dollars per patient, without any guarantee of even temporary success. Material science has also brought us CARC, a gallon or two of which could most likely do in at least a dozen unwary camouflage painters in a matter of hours or minutes and a gallon of CARC costs only thirty-five bucks.