1922: Calcutta.

Srila Prabhupada (then known as Abhay Charan De) was skeptical:

he had seen too many "holymen" at his father's house

professional beggars, ganja smokers, and the like.

But this person was different . . .

In 1916, while World War I raged in Europe, twenty-year-old Abhay Charan De entered Scottish Churches' College in Calcutta. It was a prestigious Christian school, run mostly by Scottish priests sober, moral men and many well-to-do Bengali families sent their sons there to receive a proper British education.

College life was demanding. With Abhay's rigorous schedule of classes and homework, he no longer had much time for worshiping the Deity of Krsna. Yet he resisted those Western teachings that demeaned his own devotional upbringing. As one of his classmates later noted, Abhay was always thinking about "something religious, something philosophical or devotional about God."

In college Abhay was swept up into the movement for Indian independence. One of his classmates was Subhas Chandra Bose, a firebrand in the movement. The nationalistic ideals he spoke of appealed to Abhay. At the same time, Gandhi was capturing the attention of India's masses by amalgamating Bhagavad-gita's spirituality with the call for independence from the British. Abhay became a Gandhian.

In 1920, after passing his final examinations, Abhay, as a protest against the British, refused to accept his diploma. He sacrificed a promising professional career, but he did what he and many of his countrymen felt was honorable.

Newly married, Abhay needed employment, and his father secured him a job as a department manager in the pharmaceutical laboratory of Dr. Kartik Chandra Bose. Yet Abhay continued to identify himself with Gandhi's cause. So as a businessman in the Bose establishment he wore the coarse hand-made cotton cloth known as khadi, the Gandhian alternative to the English cloth symbolic of Britain's economic stranglehold on India. On the eve of his first meeting with his spiritual master, we find Abhay a confirmed follower of Gandhi's, embarking on a career as a family man and a pharmaceutical merchant.

(Excerpted from Srila Prabhupada-lilamrta, by Satsvarupa dasa Goswami. © 1981 by the Bhaktivedanta Book Trust.)

Abhay's friend Narendranath Mullik was insistent. He wanted Abhay to see a sadhu from Mayapur. Naren and some of his friends had already met the sadhu at his nearby asrama on Ultadanga Junction Road, and now they wanted Abhay's opinion. Everyone within their circle of friends considered Abhay the leader, so if Naren could tell the others that Abhay also had a high regard for the sadhu, then that would confirm their own estimations. Abhay was reluctant to go, but Naren pressed him.

They stood talking amidst the passersby on the crowded early-evening street, as the traffic of horse-drawn hackneys, oxcarts, and occasional auto taxis and motor buses moved noisily on the road. Naren put his hand firmly around his friend's arm, trying to drag him forward, while Abhay smiled but stubbornly pulled the other way. Naren argued that since they were only a few blocks away, they should at least pay a short visit. Abhay laughed and asked to be excused. People could see that the two young men were friends, but it was a curious sight, the handsome young man dressed in white khadi kurta and dhoti being pulled along by his friend.

Naren explained that the sadhu, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, was a Vaisnava (a worshiper of Visnu) and a great devotee of Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu. One of his disciples, a sannyasi, had visited the Mullik house and had invited them to see Srila Bhaktisiddhanta. A few of the Mulliks had gone to see him and had been very much impressed.

But Abhay remained skeptical. "Oh, no! I know all these sadhus," he said. "I'm not going." Abhay had seen many sadhus in his childhood; every day his father had entertained at least three or four in his home. Some of them were no more than beggars, and some even smoked ganja. Gour Mohan had been very liberal in allowing anyone who wore the saffron robes of a sannyasi to come. But did it mean that though a man was no more than a beggar or ganja smoker, he had to be considered saintly just because he was dressed as a sannyasi or was collecting funds in the name of building a monastery or could influence people with his speech?

No. By and large, they were a disappointing lot. Abhay had even seen a man in his neighborhood who was a beggar by occupation. In the morning, when others dressed in their work clothes and went to their jobs, this man would put on saffron cloth and go out to beg and in this way earn his livelihood. But was it fitting that such a so-called sadhu be paid a respectful visit, as if he were a guru?

Naren argued that he felt that this particular sadhu was a very learned scholar and that Abhay should at least meet him and judge for himself. Abhay wished that Naren would not behave this way, but finally he could no longer refuse his friend. Together they walked past the Parsnath Jain Temple to One Ultadanga, with its sign, "Bhaktivinod Asana," announcing it to be the quarters of the Gaudiya Math.

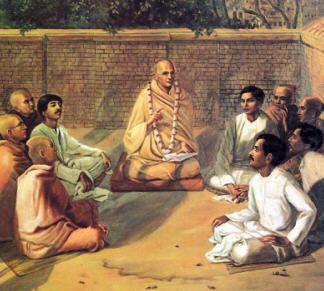

When they inquired at the door, a young man recognized Mr. Mullik Naren had previously given a donation and immediately escorted them up to the roof of the second floor and into the presence of Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, who was sitting and enjoying the early evening atmosphere with a few disciples and guests.

Sitting with his back very straight, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati appeared tall. He was slender, his arms were long, and his complexion was fair and golden. He wore round bifocals with simple frames. His nose was sharp, his forehead broad, and his expression was very scholarly yet not at all timid. The vertical markings of Vaisnava tilaka on his forehead were familiar to Abhay, as were the simple sannyasa robes that draped over his right shoulder, leaving the other shoulder and half his chest bare. He wore tulasi neck beads, and the clay Vaisnava markings of tilaka were visible at his throat, shoulder, and upper arms. A clean white brahminical thread was looped around his neck and draped across his chest. Abhay and Naren, having both been raised in Vaisnava families, immediately offered prostrated obeisances at the sight of the reveredsannyasi.

While the two young men were still rising and preparing to sit, before any preliminary formalities of conversation had begun, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta immediately said to them, "You are educated young men. Why don't you preach Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu's message throughout the entire world?"

Abhay could hardly believe what he had just heard. They had not even exchanged views, yet this sadhu was telling them what they should do. Sitting face to face with Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, Abhay was gathering his wits and trying to gain a comprehensible impression, but this person had already told them to become preachers and go all over the world!

Abhay was immediately impressed, but he wasn't going to drop his intelligent skepticism. After all, there were assumptions in what the sadhu had said. Abhay had already 'announced himself by his dress to be a follower of Gandhi, and he felt the impulse to raise an argument. Yet as he continued to listen to Srila Bhaktisiddhanta speak, he also began to feel won over by the sadhu's strength of conviction. He could sense that Srila Bhaktisiddhanta didn't care for anything but Lord Caitanya and that this was what made him great. This was why followers had gathered around him and why Abhay himself felt drawn, inspired, and humbled and wanted to hear more. But he felt obliged to make an argument to test the truth.

Drawn irresistibly into discussion, Abhay spoke up in answer to the words Srila Bhaktisiddhanta had so tersely spoken in the first seconds of their meeting. "Who will hear your Caitanya's message?" Abhay queried. "We are a dependent country. First India must become independent. How can we spread Indian culture if we are under British rule?"

Abhay had not asked haughtily, just to be provocative, yet his remark was clearly a challenge. If he were to take this sadhu's remark as a serious one and there was nothing in Srila Bhaktisiddhanta's demeanor to indicate that he had not been serious Abhay felt compelled to question how he could propose such a thing while India was still dependent.

Srila Bhaktisiddhanta replied in a quiet, deep voice that Krsna consciousness didn't have to wait for a change in Indian politics, nor was it dependent on who ruled. Krsna consciousness was so important so exclusively important that it could not wait.

Abhay was struck by his boldness. How could he say such a thing? The whole world of India beyond this little Ultadanga rooftop was in turmoil and seemed to support what Abhay had said. Many famous leaders of Bengal, many saints, even Gandhi himself, men who were educated and spiritually minded, all might very well have asked this same question, challenging this sadhu's relevancy. And yet he was dismissing everything and everyone as if they were of no consequence.

Srila Bhaktisiddhanta continued: Whether one power or another ruled was a temporary situation; but the eternal reality is Krsna consciousness, and the real self is the spirit soul. No manmade political system, therefore, could actually help humanity. This was the verdict of the Vedic scriptures and the line of spiritual masters. Although everyone is an eternal servant of God, when one takes himself to be the temporary body and regards the nation of his birth as worshipable, he comes under illusion. The leaders and followers of the world's political movements, including the movement for svaraj, were simply cultivating this illusion. Real welfare work, whether individual, social, or political, should help prepare a person for his next life and help him reestablish his eternal relationship with the Supreme.

Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati had articulated these ideas many times before in his writings:

There has not been, there will not be, such benefactors of the highest merit as [Chaitanya] Mahaprabhu and His devotees have been. The offer of other benefits is only a deception; it is rather a great harm. whereas the benefit done by Him and His followers is the truest and greatest eternal benefit. . . . This benefit is not for one particular country causing mischief to another; but it benefits the whole universe. . . . The kindness that Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu has shown to jivas [souls] absolves them eternally from all wants, from all inconveniences and from all distresses. . , . That kindness does not produce any evil, and the jivas who have it will not be the victims of the evils of the world.

As Abhay listened attentively to the arguments of Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, he recalled a Bengali poet who had written that even less advanced civilizations, like China and Japan, were independent and yet India labored under political oppression. Abhay knew well the philosophy of nationalism, which stressed that independence had to come first. An oppressed people was a reality, the British slaughter of innocent Indian citizens was a reality, and independence would benefit people. Spiritual life was a luxury that could be afforded only after independence. In the present times, the cause of national liberation from the British was the only relevant spiritual movement. The people's cause was in itself love of God.

Yet because Abhay had been raised a Vaisnava, he appreciated what Srila Bhaktisiddhanta was saying. Abhay had already concluded that this was certainly not just another questionable sadhu, and he perceived the truth in what Srila Bhaktisiddhanta said. This sadhu wasn't concocting his own philosophy, and he wasn't simply proud or belligerent, even though he spoke in a way that kicked out practically every other philosophy. He was speaking the eternal teachings of the Vedic literature and the sages, and Abhay loved to hear it.

Srila Bhaktisiddhanta, speaking sometimes in English and sometimes in Bengali, and sometimes quoting Sanskrit verses of the Bhagavad-gita, spoke of Sri Krsna as the highest Vedic authority. In the Bhagavad-gita Krsna had declared that a person should give up whatever duty he considers religious and surrender unto Him, the Personality of Godhead (sarva-dharman parityajya mam ekam saranam vraja). And theSrimad-Bhagavatam confinned the same thing. Dharmah projjhita-kaitavo 'tra paramo nirmatsaranam satam: all other forms of religion are impure and should be thrown out, and only bhagavata-dharma,performing one's duties to please the Supreme Lord, should remain. Srila Bhaktisiddhanta's presentation was so cogent that anyone who accepted the scriptures would have to accept his conclusion.

The people were now faithless, said Bhaktisiddhanta, and therefore they no longer believed that devotional service could remove all anomalies, even on the political scene. He went on to criticize anyone who was ignorant of the soul and yet claimed to be a leader. He even cited names of contemporary leaders and pointed out their failures, and he emphasized the urgent need to render the highest good to humanity by educating people about the eternal soul and the soul's relation to Krsna and devotional service.

Abhay had never forgotten the worship of Lord Krsna or His teachings in Bhagavad-gita. And his family had always worshiped Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu, whose mission Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati was espousing. As these Gaudiya Math people worshiped Krsna, he also had worshiped Krsna throughout his life and had never forgotten Krsna. But now he was astounded to hear the Vaisnava philosophy presented so masterfully. Despite his involvement in college, marriage, the national movement, and other affairs, he had never forgotten Krsna. But Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati was now stirring up within him his original Krsna consciousness, and by the words of this spiritual master not only was he remembering Krsna, but he felt his Krsna consciousness being enhanced a thousand times, a million times. What had been unspoken in Abhay's boyhood, what had been vague in Jagannatha Puri, what he had been distracted from in college, what he had been protected in by his father now surged forth within Abhay in responsive feelings. And he wanted to keep it.

He felt himself defeated. But he liked it. He suddenly realized that he had never before been defeated. But this defeat was not a loss. It was an immense gain.

Srila Prabhupada: I was from a Vaisnava family, so I could appreciate what he was preaching. Of course, he was speaking to everyone, but he found something in me. And I was convinced about his argument and mode of presentation. I was so much struck with wonder. I could understand: Here is the proper person who can give a real religious idea.

It was late. Abhay and Naren had been talking with him for more than two hours. One of the brahmacaris gave them each a bit of prasadam in their open palms, and they rose gratefully and took their leave.

They walked down the stairs and onto the street. The night was dark. Here and there a light was burning, and there were some open shops. Abhay pondered in great satisfaction what he had just heard. Srila Bhaktisiddhanta's explanation of the independence movement as a temporary, incomplete cause had made a deep impression on him. He felt himself less a nationalist and more a follower of Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati. He also thought that it would have been better if he were not married. This great personality was asking him to preach. He could have immediately joined, but he was married; and to leave his family would be an injustice.

Walking away from the asrama. Naren turned to his friend: "So, Abhay, what was your impression? What do you think of him?"

"He's wonderful!" replied Abhay. "The message of Lord Caitanya is in the hands of a very expert person."

Srila Prabhupada: I accepted him as my spiritual master immediately. Not officially, but in my heart. I was thinking that I had met a very nice saintly person.

The biography of Srila Prabhupada continues in our next issue with a look into the lives of his own spiritual teachers.