At School With Krsna's Canadian Kids

In Vancouver, children at a Hare Krsna school learn and play in an atmosphere of love.

They rise at 4:00 a.m., chant Hare Krsna and dance, and stand respectfully when their teachers enter the classroom. They're vegetarians, they don't watch cartoons, and they do their own laundry.

Too disciplined? I thought the children at the Hare Krsna gurukula school in Vancouver were having a lot of fun.

With my heavy black camera bag slung over my shoulder, I knocked at the door that said "Bala Krsna dasa, Headmaster." His wife, Madhumati-devi dasi, greeted me with a smile and showed me in. Bala Krsna and I liked each other straightaway.

I asked him how the children were doing academically. "These kids are really bright," he said. "They're reading better than most other children their age. Also, they're protected from drugs and other bad influences, and they're jubilant."

"Sounds great," I said. "But is it really that great?" He invited me to talk with some of the parents and visit the classrooms.

I met Bahudaka dasa, president of the Vancouver Krsna center and father of seven. "It's amazing how fast our students learn to read," he said. "All of my children learned extremely quickly. My son Kunjavihari, for example, first attended the gurukula in Philadelphia. In the middle of second grade he took a standardized reading test and scored at the ninth-grade level. My second daughter, Syama-gauri, is now in second grade, but she's reading at the level of an eighth-grader. My wife Nirupama teaches the older girls, and she tells me this kind of achievement isn't unusual."

I went to see the class for beginning girls and found them out on the lawn.

"You stand over there with Laksmana," one girl directed, "and this time you be Sita, I'll be Rama, and she'll be Hanuman. O.K., bring Sita the message."

The girls were playing a scene from the Vedic classic Ramayana a scene they'd picked up from the temple's videocassette player. Suddenly a teacher appeared at the classroom door: "Play time is over now. Everyone come inside."

As they scrambled in I followed and sat down to watch.

The four youngest girls (around five years old) sat down at a low table beneath a bay window at the front of the room and started practicing how to print letters. At the other end three older girls sat reading.

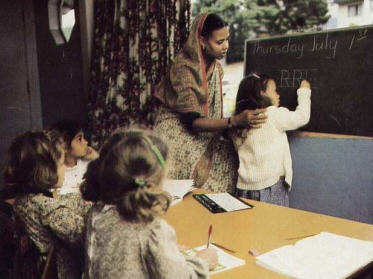

Harirani-devi dasi (the kids call her Mother Harirani) sat down at another low table to help six-year-old Krsna-devata as she carefully sounded out each word from a primer. Then Harirani got up and began demonstrating a new letter to the youngest girls. "Today we're learning R," she announced. "Down . . . around . . . and down." She drew it three times on the blackboard. "All right, who will try?"

One by one the children in the youngest group went to the blackboard and shakily drew their R's, and when one girl gave hers a crooked leg, everyone (including her) had a big laugh.

Throughout the school I saw that the teachers knew how to be firm "Kalindi, are you doing your work?" but also playful and loving. Both teachers and students were having a good time.

Later, I asked Harirani to tell me something about her teaching. "One of the things I teach the children is the Bhagavad-gita. Of course, the Bhagavad-gita is a highly philosophical work, so they can't read all of it right away. But it's also a fascinating story. So we have been learning it as a play. All together, we memorize each character's lines. Then we rehearse, with each child playing a different part. Finally, we perform with full costume and make-up.

"Because of the Bhagavad-gita play we have all become very close. It's hard to explain, but by glorifying Krsna together we've developed a very special feeling for each other. Most of the time we have a regular academic schedule, but the children like this part of their education the best."

I asked Harirani how she felt teaching in the gurukula might compare with teaching in a public school.

"In public schools, teachers don't expect to see their students much more than a few hours a day for several months. For most teachers, teaching's just a job. But we grow with these kids. We live with them, and we'll see them through their whole education. The teachers, the students, and the other members of the community are like a big family. I'm like a mother to the children; I see them as I would my own.

"Since I'm with the children steadily, I know their personalities, and I'll know the whole context of their lives if they develop problems. A public-school teacher has to be less involved, since the children come and go so quickly. Plus, he has to look out for his job, which depends on how his students perform on standardized tests. So he'll often try to instill fear of failure in his students to motivate them. We can concentrate on cultivating a positive enthusiasm for learning in each child."

When I walked into the boys' classroom, they all stood up and greeted me. Surprised by the reception, I returned the greeting and then sat down at the back of the room. At the next break they began telling me about some of the things they'd learned.

"One day we looked at swamp water through a microscope and saw lots of little tubes swimming around," recalls nine-year-old Gopinatha. "We learned in our nature class that they're tiny animals that live by eating even smaller one-celled plants."

I asked the boys what they learned in gurukula that children in public schools don't.

"Krsna consciousness!" said ten-year-old Gauracandra. "We learn everything they learn like English, arithmetic, history, and geography but we also learn Sanskrit, the Bhagavad-gita, and how to know Krsna. So our education will get us out of the cycle of birth and death, but theirs will keep them in it."

Then he turned to a Visible Man model on the table. "See," he said, "here's the Spine, and here's the rib cage, the lung, and the heart. They're parts of the body, like parts of a machine. But what the model doesn't show is the soul. The soul is inside the body, like the driver of a car. It's not very smart to think 'I am the machine. I am the car.' You have to know you're a spirit soul."

We heard a whistle. The boys said it meant they were due at their asrama, the house where they live, and they scampered out the door.

After a few days I'd made friends with all the children. I had watched an older girls' sewing class, gone swimming with the boys, sat in on a drama performance, and even caught the debut of Devaki's pet lizard. On Friday we'd gone together to the garden, where the children were all helping to pick peas and pull weeds.

One day the boys invited me to their asrama for lunch. There I met their asrama teachers, Jaya Gauracandra dasa and his wife, Atmarama-devi dasi, who live with the eight boys and carefully watch over them.

I learned the boys' daily schedule: They rise before 4:00 am. and attend the first worship ceremony in the temple. Then they chant Hare Krsna together quietly, listen with the adults to the morning class on the Vedic scripture Srimad-Bhagavatam, have breakfast, and go to school. (The girls' schedule is the same.)

Jaya Gauracandra expects each boy to be responsible to take his turn cleaning the bathroom and the floors, to help prepare meals and wash dishes, to fold the laundry, and to watch out for his own personal needs. All the while Jaya Gauracandra and his wife instruct and encourage the boys.

"Srila Prabhupada wanted us to be strict with them, to make sure they don't become lazy," he said. "But he also taught us that the basis of strictness must be love. The children can benefit from our strictness and instruction only when they know we love them."

I was impressed with Jaya Gauracandra's dedication to the children. Certainly a working parent couldn't give his own children such attention.

I was also glad to note that the children's parents were close by. They live in the same community, worship with their children in the temple each morning, and see them running outside at play time. When thegurukula presents a play, the audience is full of parents. The children spend Sundays at home, and home is where they live during vacations.

Before leaving, I met with Bala Krsna again. He showed me a book entitled Srila Prabhupada on Gurukula. It's a recent publication compiled by His Holiness Jagadisa Goswami, the Hare Krsna movement's minister of education.

"I've picked out some passages to read to you," said Bala Krsna, "so you can understand the ultimate goal of gurukula education." He read out loud:

A Krsna conscious student can immediately give up all illicit sex, gambling, meat-eating, and intoxication, whereas those who are not in Krsna consciousness, although they may be very highly educated, are often drunkards, meat-eaters, sex-mongers, and gamblers. This is practical proof of how a Krsna conscious person becomes highly developed in good qualities, whereas a person who is not in Krsna consciousness cannot do so.

"Our teachers are free from these sinful activities," Bala Krsna said. "They're examples for the students. 'Do as I say, not as I do' never works. In another place Srila Prabhupada wrote,

Modern civilization has advanced considerably in the field of mass education, but the result is that people are more unhappy than ever before because of the stress placed on material advancement to the exclusion of the most important part of life, the spiritual aspect. . . . Modern civilization is a patchwork of activities meant to cover the perpetual miseries of material existence. Such activities are aimed toward sense gratification, but above the senses is the mind, and above the mind is the intelligence, and above the intelligence is the soul. Thus the aim of real education should be self-realization, realization of the spiritual values of the soul.

"In other words," Bala Krsna concluded, "Srila Prabhupada had a far-reaching goal in mind when he founded the gurukula educational system: to awaken the spiritual nature of the children so they can get out of repeated birth and death in this material world and live eternally with the Supreme Lord, Krsna, in His transcendental abode."

After some time I thanked Bala Krsna for his hospitality and started packing for the trip home. Bahudaka offered to drive me to the airport. On the way he told me some more of his thoughts about gurukulaeducation.

"You know," he said, "children need a teacher they can have full faith in. They can't succeed without one. I understood this better recently when I began taking flying lessons. There's a maneuver in which the teacher puts the plane into a spin and then shows you how to pull out of it. Then you have to try. You're falling through the air, so your natural reaction is to turn the wheel back against the spin. But if you do that, you just increase the spin and end up crashing. You have to learn from the teacher how to keep a neutral wheel, ride with the spin, dive right down toward the ground, and pull out. Instead of reacting on reflex, you have to act on knowledge, on what you learned in training.

"My life was in the teacher's hands I was totally dependent on him. Similarly, in gurukula a child is dependent on his teachers to show him how to develop strong character, intelligence, and spiritual knowledge. With these he will be equipped to face the dangers that come when you try to lead a disciplined spiritual life in today's world. He won't easily fall prey to the lures of illicit sex, drugs, and other things that would cause him to crash in misery.

"My two eldest children are both hitting teenage years now, but they aren't showing the usual teenage problems promiscuity, drug abuse, rebellion, confusion. They're respectful, truthful, self-controlled, and eager to help."

We soon reached the airport, and he dropped me off.

I entered the bustling airport terminal. Passing by a newsstand, I saw the latest U. S. News & World Report. Looking out from the cover was a sullen ten-year-old with a shock of red hair. The headline: "Our Neglected Kids."

With relief I recalled that my four-year-old daughter would soon be entering gurukula.