After he arrived in America, in September of 1965, Srila Prabhupada stayed at a family's apartment in Butler, Pennsylvania, nest at an impersonalist yogi's asrama in uptown Manhattan, and then in a tint room on Seventy-second Street. By March of 1966, a few young people were coming to hear him speak, but his circumstances were still humble: he had seen no real breakthrough in his work to spread Krsna consciousness. When a thief made off with what little he had, Srila Prabhupada reconsidered his students' requests that he move downtown.

One day in April, 1966, someone broke into Srila Prabhupada's room on Seventy-second Street and stole his typewriter and tape recorder. As Prabhupada returned to the building, the janitor informed him of the theft. An unknown burglar had broken the transom glass above the door, climbed through, taken the valuables, and escaped. As Prabhupada heard the details of the crime, he became convinced that it was the janitor himself who had broken in and stolen his things, and that the man was now offering a fictitious account of a thief who had gone through the transom. Knowing there was no way he could prove this, Srila Prabhupada simply accepted his loss with disappointment. In a letter to India, he described the theft as a loss of more than one thousand rupees ($125.00).

It is understood [he wrote] that such crime as has been committed in my room is very common in New York. This is the way of material nature. American people have everything in ample, and the worker gets about Rs. 100 as daily wages. And still there are thieves for want of character. The social condition is not very good.

Before long, acquaintances were offering Srila Prabhupada replacements for his old typewriter and tape recorder. But he had lost his spirit for living in Room 307. What would prevent the janitor from stealing again whenever he desired? Srila Prabhupada began to reconsider the requests of young men like Bill Epstein and Harvey Cohen that he relocate downtown, where he would find a more interested following among the younger people. Then Harvey Cohen offered Srila Prabhupada residence in his art studio on the Bowery.

Harvey Cohen had been working as a commercial artist for a Madison Avenue advertising firm when a recently acquired inheritance spurred him to move into a loft on the Bowery to pursue his own career as a painter. But he was becoming disillusioned with New York. A group of acquaintances addicted to heroin had been coming around and taking advantage of his generosity, and his loft had recently been burglarized. He decided to leave the city for California, but before leaving, he directly offered his loft for Prabhupada to share with a boy named David Allen. Prabhupada considered it a timely offer his mission, Harvey Cohen had advised, would be more successful near the downtown area. So Prabhupada accepted the Bowery loft as his new residence.

As Prabhupada was preparing to leave his Seventy-second Street address, an acquaintance, an electrician who worked in the building, came to warn him. The Bowery was no place for a gentleman, he protested. It was the most corrupt place in the world. Prabhupada's things had been stolen from Room 307, but moving to the Bowery was not the answer. The electrician urged Prabhupada to take his friendly advice: "No, Swamiji, you cannot go there!" But Prabhupada had decided that an auspicious offer was being made. Now he wanted to go forward, and he disregarded warnings of the Bowery's dangers. As he would later say, "I couldn't understand the difference between friends and enemies. My friend was shocked to hear that I was moving to the Bowery, but although I passed through many dangers, I never thought that 'this is danger: Everywhere I thought, 'This is my home.' "

Between Harold's and the Half Moon

Srila Prabhupada's new home, the Bowery, had a long history. In the early 1600's, when Manhattan was known as New Amsterdam and was controlled by the Dutch West Indies Company, Peter Minuit, the Governor of New Netherland, staked out a north-south road, which was called "the Bowery" because a number of boweries, or farms, lay on either side. It was a dusty country road, lined with quaint Dutch cottages and bordered by the peach orchards growing on the estate of Peter Stuyvesant. It became part of the high road to Boston and was of strategic importance during the American Revolution as the only land entrance to New York City.

In the early 1800's, the Bowery was predominated by German immigrants, later in the century it became predominantly Jewish, and gradually it became the city's center of theatrical life. However, as a history of Lower Manhattan describes, 'After 1870 came the period of the Bowery's celebrated degeneration. Fake auction rooms, saloons specializing in five-cent whiskey and knock-out drops, sensational dime museums, filthy and rat-ridden stale beer dives, together with Charles M. Hoyte's song, 'The Bowery! The Bowery! I'll Never Go There Any More!', fixed it forever in the nation's consciousness as a place of unspeakable corruption."

The reaction of Srila Prabhupada's electrician friend was not unusual. The Bowery is still known all over the world as a skid row, a place of ruined and homeless alcoholics. Perhaps the uptown electrician had done business in the Bowery and had seen the derelicts who at various times sat and passed a bottle or lay unconscious in the gutter or staggered up to passersby, drunkenly bumping into them and asking for money.

Most of the Bowery's 7,600 homeless men slept in lodging houses that required them to vacate the rooms during the day. Having nowhere else to go and nothing else to do, they would loiter on the street standing silently on the sidewalks, leaning against walls, or shuffling slowly along, alone or in groups. In cold weather they would wear two coats and several suits of clothes at once and would sometimes warm themselves around a fire they would keep going in a city garbage can. At night those without lodging crawled into discarded boxes, slept on the sidewalks, on doorsteps, and street corners, or sprawled side by side next to the bars. Thefts were commonplace; a man's pockets might be searched ten or twenty times while he slept. The rates of hospitalization and death in the Bowery were five times higher than the national average, and many of the homeless men bore marks of recent injuries or violence.

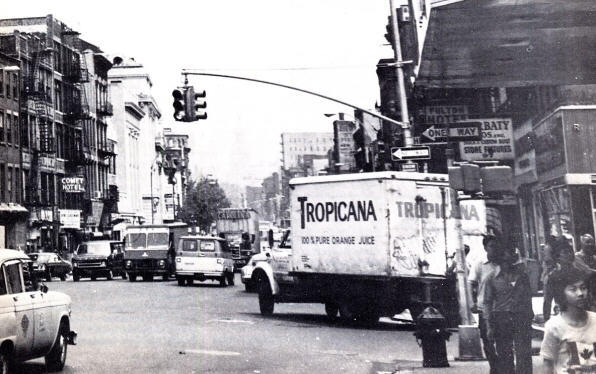

Prabhupada's loft, at 94 Bowery, was six blocks south of Houston Street. At Houston and Bowery, derelicts converged in the heavy cross-town traffic. When cars stopped for the light, bums would come up and wash the windshields and ask for money. South of Houston, the first blocks held mostly restaurant supply stores, lamp stores, taverns, and luncheonettes. The buildings were of three and four stories old, narrow, crowded tenements, their faces covered with heavy fire escapes. Traffic on the Bowery ran uptown and downtown. Cars parked on both sides of the street, and the constant traffic passed tightly. During the business day, working people passed briskly among the slow-moving derelicts. Many of the store windows were covered with protective iron gates, but behind the gates the store owners lit their varieties of lamps and arrayed their other merchandise to attract prospective wholesale and retail customers.

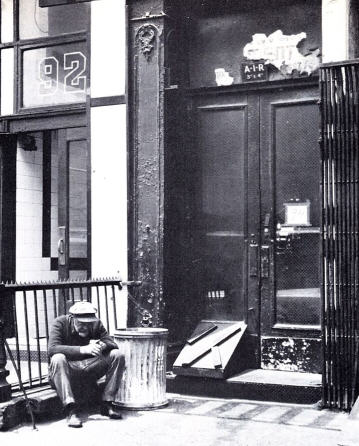

Ninety-four Bowery was just two doors north of Hester Street. The corner was occupied by the spacious Half Moon Tavern, which was frequented mostly by neighborhood alcoholics. Above the tavern sat a four-story Bowery flophouse marked by a neon sign "Palma House" which was covered by a protective metal cage and hung from the second floor on large chains. The hotel's entrance at 92 Bowery (which had no lobby, but only a desolate hallway covered with dirty white tiles) was no more than six feet from the entrance to 94.

Ninety-four Bowery was a narrow, four-story building. It had long ago been painted gray and bore the usual facing of massive black fire escapes. A well-worn black double door, its glass panels reinforced with chicken wire, opened onto the street. The sign above the door read "A.I.R. third and fourth floors," indicating that artists-in-residence occupied those floors.

The first floor of the next building north, 96 Bowery, was used for storage, and its front entrance was covered with a rusty iron gate. At 98 Bowery was another tavern Harold's smaller and dingier than the Half Moon. Thus the block consisted of two saloons, a flophouse, and two buildings with lofts.

Temple in a Loft

In the 1960's, loft living was just beginning in that area of New York. The city had given permission for painters, musicians, sculptors, and other artists (who required more space than available in most apartments) to live in buildings that had been constructed in the nineteenth century as factories. After these abandoned factories had been fitted with fireproof doors, bathtubs, shower stalls, and heating, an artist could inexpensively use a large space. These were the A.I.R. lofts.

Harvey Cohen's loft, on the top floor of 94 Bowery, was an open space almost a hundred feet long (from east to west) and twenty-five feet wide. It received a good amount of sunlight on the east, the Bowery side, and it also had windows at the west end, as well as a skylight. The exposed rafters of the ceiling were twelve feet above the floor.

Harvey Cohen had used the loft as an art studio, and racks for paintings still lined the walls. A kitchen and shower area were partitioned off in the northwest corner, and a room divider stood parallel with the Bowery about fifteen feet from the Bowery-side windows. This divider did not run from wall to wall, but was open at both ends, and it was several feet short of the ceiling.

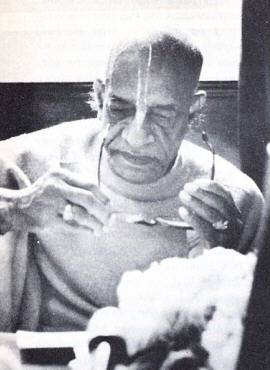

It was behind that partition that Srila Prabhupada had his personal living area. A bed and a few chairs stood near the window, and Prabhupada had set his typewriter on his metal trunk, next to the small table where he kept his stacks of Bhagavatammanuscripts. He had also strung a clothesline for drying his dhotis.

On the other side of the partition was a dais, about ten feet wide and five feet deep, on which Prabhupada sat during his kirtanas and lectures. The dais faced west, toward the loft's large open space. In that open area were a couple of rugs and an old-fashioned solid wood table. Before leaving for California, Harvey had painted a canvas depicting Lord Caitanya dancing with His associates, and this stood on an easel in the open area.

The loft was a four-flight walk up, and the only entrance, usually heavily bolted, was a door in the rear, at the west end. This door opened into a hallway, which led to the right for a few steps and finally into the open area. If a guest entered during akirtana or lecture, he would see Srila Prabhupada about thirty feet from the entrance, seated on his dais. At other times, a guest might enter and find the whole loft dark, with a light visible only on the other side of the partition, where Prabhupada was working.

Srila Prabhupada was living on the Bowery, sitting under a small light, while hundreds of derelicts also sat under hundreds of naked lights on the same city block. He had no more fixed income than any derelict in the area, nor any greater surety of a permanent residence. Yet his consciousness was entirely different. He was translating Srimad-Bhagavatam into English, speaking to the world through his Bhaktivedanta purports. His duty, whether in a fourteenth-floor apartment on Riverside Drive or in a corner of a Bowery loft, was to establish Krsna consciousness as the prime necessity for all humanity. He went on with his translating and with his constant planning and dreaming of a temple for Krsna in New York City. Because his consciousness was absorbed in Krsna's universal mission, he did not depend on his surroundings for shelter. Home for him was not a matter of bricks and wood, but of taking shelter of Krsna in every circumstance. As Prabhupada had said to his friends uptown, "Everywhere is my home," whereas without Krsna's shelter the whole world would be a dangerous place.

Often, Srila Prabhupada would refer to a scriptural statement that people in the material world live in three different modes: goodness, passion, and ignorance. Life in the forest is in the mode of goodness, life in the city is in passion, and life in a degraded place like a liquor shop, a brothel, or the Bowery is in the mode of ignorance. But to live in a temple of Visnu is to live in the spiritual world, Vaikuntha, which is transcendental to all three material modes.

But is a Bowery loft a temple? At least this loft, when Prabhupada was holding his meetings and performing kirtana there, unquestionably was. And when he was behind the partition, working in his corner before the open pages of Srimad- Bhagavatam,that room was as good as his room back at Radha-Damodara temple in Vrndavana, India.

"The Energy of Being Close to Him"

News of the Swami's presence in the Bowery loft spread, mostly by word of mouth at the Paradox restaurant, and people began to come by in the evening to hear and chant with him. The musical kirtanas were especially popular on the Bowery, since the Swami's new congregation consisted mostly of local musicians and artists, many of whom responded more to the transcendental music than to the philosophy. Every morning he would hold a class on Srimad-Bhagavatam, attended usually by David Allen, Robert Nelson, and another boy, and he would 'still occasionally teach cooking to whoever was interested. He was almost always available for personal talks with any inquiring visitors or with his new roommate David.

David Allen had heard that Harvey Cohen was moving to San Francisco if he could sublet his A.I.R. loft. Harvey hadn't known David very long, but on the night before Harvey was to leave, he coincidentally met David three different times in three different sections of the Lower East Side. Harvey took this as a sign that he should rent the loft to David but he specifically stipulated that Srila Prabhupada should move in with him.

Srila Prabhupada and David Allen got on well together. Although each had his own designated living area in the large loft, the whole place soon became dominated by Srila Prabhupada's preaching activities. At first, Srila Prabhupada considered David an aspiring disciple. Writing to his friends in India, he described his relationship with the American boy.

He was attending my class at 72nd Street along with others [Prabhupada wrote], and when I experienced this theft case in my room, he invited me to his residence. So I am with him and training him. He has good prospects because already he has given up all bad habits. In this country, illicit connection with women, smoking, drinking, and eating of meats are common affairs. Besides that, there are other bad habits, like using [only] toilet paper [and not bathing] after evacuating etc. But by my request he has given up ninety percent of his old habits, and he is chanting maha-mantra regularly. So I am giving him the chance, and I think he is improving. Tomorrow I have arranged for some prasadam distribution, and he has gone to purchase some things from the market.

When David had first come to the Bowery, he appeared like a clean-cut college student. He was eighteen years old, about six feet tall, blue-eyed, handsome, and intelligent-looking. Most of his new friends in New York were older and considered him a "kid." David's family lived in the Midwest, and his mother was paying one hundred dollars monthly to sublease the loft. Although David did not have much experience, he had read that a new realm of mind expansion was available through psychedelic drugs, and he was heading fast into the hazardous world of LSD. His meeting with Srila Prabhupada came at a time of radical change and profoundly affected his life.

It was a really good relationship I had with the Swami [David relates], although I was overwhelmed by the tremendous energy of being that close to him. It spurred my consciousness very fast. Even my dreams at night would be so vivid ofKrsna consciousness. I was often sleeping when the Swami was up, because he was up late in the night working on his translations. That's possibly where a lot of the consciousness and dreams just flowed in, because of that deep relationship. It also had to do with studying Sanskrit. There was a lot of immediate impact with the language. The language seemed to have such a strong mystical quality, the way he translated it word for word.

Prabhupada's old friend from uptown, Robert Nelson, continued to visit him on the Bowery. Robert was impressed by Prabhupada's friendly relationship with David, who he saw was learning many things from the Swami. Robert bought a small American-made hand organ, similar to an Indian harmonium, and donated it to David for chanting with Prabhupada. At seven in the morning, Robert would come by, and after Bhagavatam class he would talk informally with Srila Prabhupada, telling his ideas for making records and selling books. He wanted to continue helping Srila Prabhupada as he had done uptown. They would sit in chairs near the front window, and Robert would listen while Prabhupada talked for hours about Krsna and Lord Caitanya.

Saffron in a Dingy Alcove

New people began coming to see Prabhupada on the Bowery. Carl Yeargens, a thirty-year-old black man from the Bronx, had attended Cornell University and was now independently studying Indian religion and Zen Buddhism. He had experimented with drugs as "psychedelic tools," and he had an interest in the music and poetry of India. He was influential among his friends and tried to interest them in meditation. He had even been dabbling in Sanskrit.

I had just finished reading a book [he relates] called The Wonder That Was India. I had gotten the definition of a sannyasi and a brahmacari and so forth. There was a vivid description in that particular book of how you could see a sannyasi coming down the road with his saffron robe. It must have made more than just a superficial impression on me, because it came to me this one winterish evening. I was going to visit Michael Grant probably going to smoke some marijuana and sit around, maybe play some music and I was coming down Hester Street. If you made a left on Bowery, you could go up to Mike's place on Grand Street. But it's funny that I chose to go that way, because the shorter way would have been to go down Grand Street and then make a right on Bowery. Anyway, I decided to go down Hester and then make a left, and all of a sudden I saw in this dingy alcove a brilliant saffron robe. As I passed I saw it was Swamiji knocking on the door, trying to gain entrance. There were two bums hunched up against the door. It was like a two-part door one door was sealed, and the other was locked. The two bums were lying on either side of Swamiji. One of these men had actually expired which often happened, and you had to call the police or health department to get them.

I don't think I saw the men lying in the doorway until I walked up to Swamiji and asked him, 'Are you a sannyasi?" And he answered yes. We started this conversation about how he was starting a temple, and he mentioned Lord Caitanya and the whole thing. He just came out with this flow of strange things to me, right there in the street. But I knew what he was talking about somehow. I had the familiarity of having just read this book and delved into Indian religion. So I knew that this was a momentous occasion for me, and I wanted to help him. We banged on the door, and eventually we got into the loft. He invited me to come to a kirtana, and I came back later that night for my first kirtana. From that point on, it was a fairly regular thing three times a week. At one point Swamiji asked me to stay with him, and I stayed for about two weeks.

It was perhaps because of Carl's interest in Sanskrit that Prabhupada began holding a Sanskrit class in the loft. Every day he taught a few students how to form the letters of the alphabet and pronounce the Sanskrit sounds. He used a chalkboard he had found in the loft, and his students wrote their exercises in notebooks. Carl and a few others would spend hours working on Sanskrit with Prabhupada, who would look over their shoulders to see if they were writing correctly and would review their pronunciation. The boys were learning not only Sanskrit but the instructions from Bhagavad-gita. Each day Prabhupada would give them a different verse to write down in the Sanskrit alphabet (devanagari), transliterate into the Roman alphabet, and then translate word for word into English. But their interest in Sanskrit waned, and Srila Prabhupada gradually gave up the daily classes to spend time working on his own translations of Srimad-Bhagavatam.

Prabhupada's new friends may have regarded these lessons as Sanskrit classes, but actually, of course, they were bhakti classes. Srila Prabhupada had not come to America as an ambassador of Sanskrit; his Guru Maharaja, his spiritual master, had ordered him to teach Krsna consciousness. But he had found in Carl and some of his friends a desire to investigate Sanskrit, so he encouraged it. As a youth, Lord Caitanya also had started a Sanskrit school, with the real purpose of teaching love of Krsna. He would teach in such a way that every word meant Krsna, and when His students objected He closed the school. Similarly, Prabhupada had no mission to perform on behalf of Sanskrit linguistics, and when he found that the interest of the A.I.R. bohemians in Sanskrit was transitory, he gave up holding these classes.

By the standard of classical Vedic scholars, it takes ten years to master Sanskrit grammar. And if one does not start until his late twenties or thirties, it is usually too late. Certainly none of Prabhupada's students were thinking of entering a ten-year concentration in Sanskrit grammar, and even if they were, they would not have realized spiritual truth simply by becoming grammarians. Prabhupada thought it better to use his Sanskrit background to follow the Sanskrit commentaries of the previous authorities and translate the verses of Srimad Bhagavatam into English. Otherwise, the secrets of Krsna consciousness would remain locked away in the Sanskrit. Teaching Carl Yeargens devanagari, sandhi, verb conjugations, and noun declensions was not going to give the people of America transcendental Vedic knowledge. It was better, Prabhupada thought, to use his proficiency in Sanskrit for translating many volumes of the Bhagavatam into English for millions of potential readers.