The joyful history of a dynamic transcendental movement

Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare vibrates from a walkup temple on New York's Lower East Side, from the sidewalks of Haight Ashbury, from Golden Gate Park, from a London flat, from student quarters in Hamburg and Amsterdam, from a storefront in Santa Fe, an exbowling alley in Montreal, a sprawling university campus in Ohio, from Old Vrindaban in India to New Vrindaban in the West Virginia mountains, and from Boston and Buffalo to Los Angeles, Seattle and Vancouver and across the Pacific to Hawaii.

Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. The voices chanting the magic vibrations are invariably young. The chanting, accompanied by khartals (small hand cymbals), tambourines and drums, is often loud and frenetic. The dancing is vigorous. The middle-aged and elderly usually stand in doorways or look through windows, watching in amazement, unaware that they are witnessing a process of spiritual realization that has been practiced on this planet for thousands of years. They do not understand. No one really understands. The chanting just spreads. Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna …

In a brief three years, the chanting of the Hare Krishna Mantra has exploded all over the Western world. Its chief propagator is a 73-year-old Indian monk, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, who came as a nearly penniless stranger to America in 1965 to spread the transcendental message of The Bhagavad Gita. Whoever encounters Prabhupad, as he is called by his disciples, is immediately struck by his sincerity and magnetism.

I first met him in 1966 on a bright July morning in New York City. At the time I was living in a low-rent apartment on Mott Street near Houston, on the Lower East Side. That particular July morning I remember hurrying down Houston and across Bowery, past the numberless bums and drunks, on my way to see friends at Tompkins Square. It was after I had crossed Bowery (just before Second Avenue) that I saw Prabhupad strolling down Houston, head raised, seeming a million miles away. A 70-year-old man, he looked around 50 and ambled along like a man in his 30's. He was wearing the traditional saffron-colored robes of a sannyasi, monk in the renounced order, and quaint white shoes with points. Coming down the street, he looked like the genie that popped out of Aladdin's lamp. I was fresh from a trip to India, and Prabhupad reminded me of the many holy men I had recently seen walking the dirt roads of Hardwar and Rishikesh and bathing in the Ganges. But Houston Street wasn't the Ganges.

I had to stop him, so I asked the most stupid, obvious question: "Are you from India?" and of course he stopped and beamed cordially, "Oh yes. And you?" I thought he mistook me for a Sikh because of my beard. I told him that I had just returned from India and that I was very interested in his country and Indian thought. He smiled happily and told me that he had been in New York almost ten months. Although an old man, his eyes flashed with the freshness of a child's, and I was immediately charmed.

He seemed to anticipate my questions and took a lively interest in my India trip. Then he told me, "I've a place around the corner. Perhaps you can see it and tell me if it's suitable. I plan to hold some classes." We walked around the corner of Second Avenue, and he pointed out a small storefront building between 1st and 2nd Streets next door to a filling station. It had been a curiosity shop, and someone had painted the words "Matchless Gifts" over the outside door. At the time I didn't realize how prophetic the words were.

"How is the area for having classes ?" he asked me.

"I think it's all right," I said. I knew he wouldn't attract wealthy or influential New Yorkers downtown, but I thought the EastVillage hippies would be interested enough in Indian philosophy or whatever he was offering to give him some patronage. I really didn't know what he intended to do, but I told him that his storefront was suitable just to reassure him. I recalled how hospitable the Indians were to me, and I wanted somehow to return their hospitality. I told him I would drop in to his classes with some of my friends, and he told me to come any Monday, Wednesday or Friday night at 7. Then we parted, and I hurried off to see my friends.

I'll never forget the first night I went to see Prabhupad. Four of my friends were sufficiently interested to attend his "class." When we began chanting the Hare Krishna Mantra for the first time that July night, I was reminded of the services of the monks up in Hardwar. We played khartals and answered Prabhupad with the sixteen word chant: Hare Krishna, Hare Krishna, Krishna Krishna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. Prabhupad led the chant, sitting on a dais clanging khartals rhythmically.

"It is not necessary to understand the words of the mantra," he told us.

"Just chant and listen."

He explained, however, that "Hare" was an address to the universal energy, "Rama" meant Enjoyer, and "Krishna" meant all-attractive and indicated the Absolute Truth, the Supreme Godhead. His lecture was our first introduction to what he called "Krishna Consciousness," that is, God consciousness. I think at the first meeting my friends were more impressed than I was, for I was afraid his approach was a little too esoteric to appeal to most Americans, but after the first two weeks I didn't care about his mass appeal. I became conscious that I could learn something. I remember asking him about using psychedelic drugs for self realization.

"You don't need to take anything for your spiritual life," he told me. "Your spiritual life is already here."

I knew he was right. He seemed naturally in a state of exalted consciousness, a state many try to trigger via psychedelics, and he promised he could teach me the same. "Krishna is Absolute," he told me. "Krishna and Krishna's Name are nondifferent. They are the same. You may not realize this at first, but the more you chant the clearer this will become. Now everyone is claiming God is dead or that I am God.' You just chant. Eventually you will have God dancing on your tongue."

I was willing to give it a try. When he talked about Krishna, he spoke with authority. He seemed the only person who actually knew beyond the shadow of all doubt what was really happening in the universe. He had the Vedas and Lord Krishna behind him, and he certainly made sense. My friends and I attended more meetings, and we found ourselves rising sleepily at 6 a.m. to attend morning classes too.

I hoped to get Prabhupad the support of many of the Lower East Side youth (whom the press was just beginning to call "hippies"), and knowing that poet Allen Ginsberg was in town, I sent him an invitation to one of our "Kirtans," as the ceremony of chanting and hearing a lecture is called. One evening he arrived in a Volkswagen bus accompanied by Peter Orlovsky. He brought a harmonium a hand-pumped Indian reed organ as a gift and joined in chanting. One night he even came with the Fugs, a popular rock group. The East Village Other gave Prabhupad a cover story and then The New York Times printed a story on the "new Lower East Side Swami," quoting Ginsberg that the mantra was instant "ecstasy." Prabhupad's classes were suddenly being transformed into a movement. During the night meetings the small storefront was packed. Kirtans were getting livelier. The music was sounding better and better, and people were loosening up and even dancing. The chanting, khartals, drums and harmonium were so loud that the inevitable complaints from neighbors started coming in. Curious New Yorkers crowded about the storefront window. Some laughed. Some cursed. One even threw a rock through the window, and the neighbors upstairs poured boiling water through the floor. We were in ecstasy.

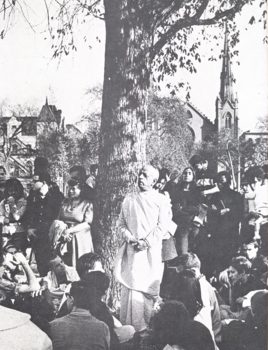

Prabhupad had prodigious energy. He was up every morning before any of us. He pounded the drum, exhausted everyone at Kirtan, chanted hymns, danced, delivered lectures, translated books, cooked and supervised all affairs. And he was triple the age of any one of us. To help spread the movement, Ginsberg suggested chanting in Tompkins Square Park where the hippies were starting to congregate. For four consecutive Sunday afternoons we held Kirtan in the center of the park. Prabhupad kept the rhythm of the Hare Krishna Mantra by pounding a small bongo drum somebody had given him. One Sunday he played the drum two hours incessantly, and his disciples practically fell out.

The crowd accepted us at first with mild enthusiasm, but they gradually warmed up, and finally the Kirtans expanded into three-hour marathons. Many of the youth would join in and dance. Some of the old Ukranian and Polish residents would stare uncomprehendingly, then walk away, shaking their heads and grumbling. Many people stood for hours on the hard concrete to join in the chanting. Poet Ginsberg joined every Sunday. I recall one Sunday when a New YorkTimes reporter asked me to bring Ginsberg over to talk to him. Ginsberg was absorbed in the chanting, but I asked him anyway. It was the only time I ever saw him annoyed. "He shouldn't interrupt a man worshiping," he said. "Tell him that." And he went right on chanting.

There were fifteen initiated disciples by that time, and our fervor was fresh. I remember writing up handbills and passing them out at Tompkins Square during our Kirtans. They were glaring, evangelical, ambitious: