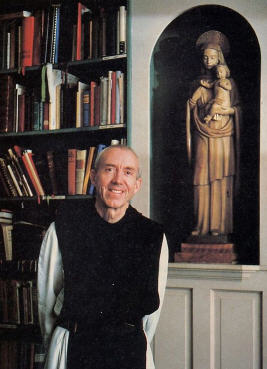

The Rt. Reverend Edward Mccorkell, O.C.S.O. is the Abbot of Holy Cross Abbey in Berryville, Virginia, and Chairman of the Board, Cistercian Publications, Inc.

The questionable activities of a man like Sun Myung Moon and his disciples, popularly known as "Moonies," and the recent tragic happening at the "People's Temple" in Guyana have caused many of us to question and reexamine the varieties of religious experience in our time. Such an examination calls for an objective, unprejudiced approach to the subject. Unfortunately, in the haste to seek easy answers to our questions, many of us have tended to study these problems a bit superficially and to make hasty judgments. One hazardous mistake has been to merge together, indiscriminately, many vastly differing religious and quasi-religious groups into one ambiguous pejorative category: "cult." It is with this in mind that I would like to share my experience of a personal encounter with a rich spiritual tradition different from my own and yet, as I discovered to my delight, one in which I have felt "at home."

I have had the pleasure of meeting and becoming a friend of a monk who is a disciple of A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. His religious name is Subhananda dasa Brahmacari. This young man first visited our monastery when he was a novice. He was wearing the traditional saffron robe and was tonsured. Up to that time, my view of these young American devotees of the Hare Krsna movement whom I had seen on the streets was somewhat negative. It appeared to me to be another fad, for which our country is well known. I tended to dismiss them and discount them as immature enthusiasts.

Thus my first encounter with this young novice about seven years ago was quite reserved. He told me his story: He was born a Jew and had grown up in the turbulent sixties, becoming a part of the drug culture and the antiwar movement. He then came in touch with the International Society for Krishna Consciousness and, after being a member for some time, was accepted as a disciple of Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. It was through this initial encounter with him that I first began to take some interest inBhagavad-gita, an excellent copy of which he kindly gave me, entitled Bhagavad-gita As It Is and containing the translation and learned commentary of Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the late founder and spiritual leader of the Krsna consciousness movement. I later discovered that Thomas Merton (one of the great monks of our Order, who had begun a serious study of and dialogue with non-Christian monasticism) had written a preface to the first edition of this work.

As a disciple of Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, Subhananda had entered into a rich tradition, stemming from roots that go back in a long, unbroken line to Lord Sri Krsna. His tradition is firmly rooted in Hindu spirituality and culture and represents the theistic, devotional side of the Indian religious tradition. In a revealing passage in an unfinished, unpublished work, The Inner Experience, Thomas Merton offers some interesting observations on my friend's religious discipline, bhakti-yoga, and his principal scripture, Bhagavad-gita:

"There are facile generalizations about Hindu religion current in the West, which it would be well to take with extreme reserve: for instance, the statement that for the Hindu, there is no 'personal God. On the contrary, the mysticism of bhaktiyoga is a mysticism of affective devotion and of ecstatic union with God under the most personal and human forms, sometimes very reminiscent of the 'bridal mysticism' of so many Western mystics.

"The Bhagavad-gita is a doctrine of pure love resembling in many points that preached by St. Bernard, Tauler, Fenelon, and many other Western mystics … The Gita, an ancient Sanskrit philosophical poem, preaches a contemplative way of serenity, detachment, and personal devotion to God in the form of Lord Krishna, expressed most of all in detached activity work done without concern for results but with the pure intention of fulfilling the will of God."

My friend came back for a second visit to our monastery more recently. I was very favorably impressed by the spiritual growth that I witnessed in him. It was quite evident that his serious commitment to the monastic life was bearing fruit. He possessed a sensitivity to theological issues and a spiritual maturity usually attained only after many years in religious training and monastic experience. In comparing my own Benedictine-Cistercian monastic tradition with his, I can see much in common: commitment to a discipline, tutelage under a spiritual master, poverty, simplicity, sacred reading and prayer, as well as celibacy.

I would like to conclude by urging readers to approach a rich tradition like this with open minds and hearts, asking the Holy Spirit of truth and charity to enlighten them and reveal to them the abundant spiritual riches to be found in that tradition. Both justice and charity call for a breaking down of the walls of prejudice in our interreligious encounters and dialogues. Discernment is needed to sift the chaff from the wheat, but prejudice is an obstacle to such discernment.