Transcendental Commentary on the Issues of the Day

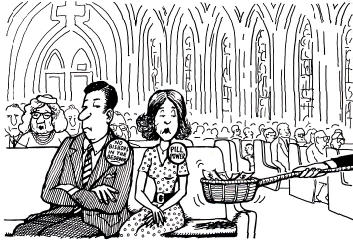

The Catholic Church in the United States is losing about $6.7 billion in donations yearly. The main reason, says Father Andrew Greeley, is that its members don't like the Church's position on marital sex.

Father Greeley, controversial author of Catholic Contributions: Sociology and Policy, says Catholics resent celibate bishops trying to control couples' sex lives. The bishops, Father Greeley complains, have too much to say about marital sex a topic Jesus preferred not to talk about.

But shouldn't Church leaders have something to say about it? Guiding the spiritual lives of the laity is surely one of their responsibilities. And since celibacy, in principle, frees them from the encumbrances of married life, permitting them to dedicate themselves to understanding the spirit of Jesus' teachings and how best to apply his teachings in the modern context, why should the bishops be disqualified from speaking up on this topic?

Some people seem to think that the only value of religion is that if you follow the rules you'll go to heaven. With the bishops making rules that conflict with the laity's sense enjoyment, the laity is opting for an easier set of rules.

But religion is not just an arbitrary system of rules. Religion is meant for purifying us so we can love God. How can we whimsically change the rules?

The bishops are somewhat at fault for not teaching their laity that religion means spiritual life, which begins with the understanding that we're not these bodies. Those protesting the Church's policy don't seem to understand that there is a difference between bodily enjoyment and spiritual enjoyment, or that for the sake of spiritual realization they have to control their sexual desire, not give it free rein.

They don't seem to realize that a preoccupation with serving the body through sex interferes with a life of service to God. They seem to forget that while Jesus may not have said anything about marital sex, he surely had something to say about the pleasures of the flesh.

Sex is only important to a person in bodily consciousness, who doesn't understand that the body will turn to ash and the soul will live on. But a person in spiritual consciousness understands this, and he or she naturally shuns sex. That people are so disturbed by the Church's teachings on sex indicates they are very much in the bodily concept of life and are not satisfied with spiritual knowledge. They are not getting a spiritual taste from their religion.

But they shouldn't blame the religion. They should blame their own unwillingness to undergo austerity for spiritual advancement. Only by following scriptural standards can one gradually become free from sensual desire, derive a spiritual taste, and get in touch with God by developing a desire to serve Him purely, without any selfish motive based on the body.

The Krsna consciousness movement's restrictions on sex are more difficult than those the bishops advocate, which is probably one reason why more people don't take up Krsna consciousness. They are not willing to give up sex pleasure which is widely accepted as the highest material pleasure. In actuality, sex enjoyment is the greatest cause of bondage for the embodied soul because it reinforces the bodily conception of life.

Sex is as people often hasten to argue natural. And childbirth is its natural result. Contraception, on the other hand, is not natural; birth control pills don't grow on trees.

We can use sex to bring a child into the world, but we must also understand our responsibility to guide that child in spiritual life. Sex with that purpose in mind is not only unrestricted, it is glorious. Krsna confirms in Bhagavad-gita: "I am sex life that is not contrary to religious principles." Religious sex invokes the presence of God. Irreligious sex only increases our entanglement in material life.

A Preference For Purity

by Kundali dasa

We've had three major scandals in leadership so far in 1987: the alleged adultery of former presidential hopeful Gary Hart; the unlawful involvement of Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North and his supporters in the Iran-contra arms deal; and the adulterous liaison and misappropriation of church funds by the televangelist Jim Bakker.

One columnist, in commenting on the public's reaction to these scandals, wrote, approvingly, "Whatever you may say about the American people, they like purity in their leaders." It certainly appears that way, judging by the public uproar caused by the scandals of Mr. Hart, Mr. Bakker, and Col. North.

Undeniably leaders in all fields have a primary responsibility to be exemplary, for, as Lord Krsna says, whatever great men do, ordinary men follow in their footsteps. That's our natural psychology, and therefore the hue and cry over these three leaders' less-than-exemplary conduct seems inevitable and appropriate.

Still, one wonders if many of the people clamoring for purity are themselves innocent of the sort of conduct they abhor in their political and spiritual leaders.

Take, for example, the reporters, columnists, and so forth who exposed Mr. Hart and hounded him out of the presidential race. Are they all more honorable as husbands or fathers than he?

Or the people outraged at the Iran-contra shenanigans. Are they all more law-abiding citizens than Colonel North?

Or the Christians in a tiff about Mr. Bakker's backsliding. Are all of them innocent of similar transgressions?

Sure we demand a higher standard from a public figure, and rightly so, but aren't we all leaders on some level, even if only as fathers or mothers?

In other words, if we were to first apply the guideline "Judge not lest you be judged," how many people could actually pit themselves against Mr. Hart, Mr. Bakker, or Col. North as better models of moral conduct?

It would be interesting to find out.

It is by all means commendable to want purity in our leaders, but what would be the practical value unless we were willing to become pure ourselves? If we did get such leaders, would we take moral directions from them. I think not.

Case in point: The other day I was visiting some relatives who are severely critical of the three persons in question. Our conversation eventually wandered into the topic of abortion, and someone said, "I can't believe it! Reagan thinks it's cheaper to have an unwanted child than to fund abortion. That's ridiculous."

"He believes abortion is taking a life," someone else responded. "He thinks continence is a better solution."

"Continence might be a solution for Nancy Reagan," said another, which drew a round of laughter. "Actually, it was probably her idea in the first place," she added, to more laughter. "But I don't think President Reagan has the right to decide what I should do with my sex life."

Except for me, more an observer than a participant, all present voiced their hearty agreement with her verdict. How could Ronald Reagan dare suggest what we should do when it comes to our sex life?

I said nothing, thinking it folly to disagree where lampooning is bliss. Similarly, in New York, where Mayor Koch advocates continence as a solution to the AIDS outbreak, his suggestion has met great resistance and has been labeled impractical.

But why? Continence is a singularly good proposal to counter problems like abortion and AIDS. It strikes right at the heart of these problems. We take drastic steps to minimize drunk driving. We campaign against smoking in the work place and in public places like buses and restaurants. If sex life presents a threat to life, either for unborn babies or AIDS victims, why not counter it with continence? Surely it would help.

But no, we think promiscuity our inviolable right no matter what its price, whether it's murder or terminal disease. Sex is sacrosanct. To advocate continence is to be received like a person holding forth about God at an atheists' convention.

We challenge moral decisions that conflict with our sense gratification, and yet we demand that our leaders be paragons of virtue.

Finally, though we supposedly want purity in our leaders, which ideally would mean leaders with saintly character, I cannot imagine a saintly person running for public office on a purity ticket and actually getting elected.

This leads me to wonder what exactly is meant by "American people like purity in their leaders."

Could it be that by purity we really mean we simply prefer not to know about their moral improprieties?