Tamala Krishna Goswami discusses the power of drama to convey transcendental emotion.

Well known in India are Sanskrit classical dramas devoted to Lord Krsna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead, and to His incarnations and His great devotees. These dramas, based on the epicsMahabharata, Ramayana, and Srimad-Bhagavatam, follow the rules of drama found in the Natya-sastra, the world's oldest manual on play-writing.

Recently Tamala Krishna Goswami, a senior devotee in the Hare Krsna movement, delved into this storehouse of dramatic literature and wrote two plays based on the Sanskrit dramatic form. Although composed in English, the plays conform in detail to the requirements of Sanskrit drama both in subject and in technique. This interview took place last June in New York City.

Back to Godhead: What brought about your interest in the traditional Indian theater, or Sanskrit classical drama?

Tamala Krishna Goswami: My interest in theater began in college with courses on modern drama. After joining ISKCON, I approached Srila Prabhupada with the suggestion that I might write a drama about Lord Caitanya, and Prabhupada allowed me several interviews in which he sketched Lord Caitanya's life. But nothing came of that.

Tamala Krishna Goswami

Following Prabhupada's passing away in 1977, I meditated on the idea of communicating what I and others had undergone while serving him during the final year of his life. I had been his secretary and had kept a detailed diary of those days. But since Prabhupada had authorized that his biography be written by Satsvarupa Maharaja, I turned my diary over to him.

Thereafter I wrote Servant of the Servant, a semi-autobiography based on the letters Prabhupada had sent me over the years. I ended that book with the letters I had received in 1976, still thinking I'd deal separately with 1977.

After Prabhupada's biography appeared, I felt even more strongly a need to present his final activities in a format that would fully bring out the tremendous emotional impact they had on us. It was then that I conceived of writing in the dramatic genre. I began reading classical and modern Western dramas, but I felt dissatisfied because the approach was either comic or tragic, and Prabhupada's departure was neither. I started searching for a dramatic style or tradition embodying the Vedic philosophy of the soul's eternality and the meaningfulness of life as opposed to the meaninglessness expressed in existential dramas a tradition coinciding with the world view we have in the Krsna conscious way of life.

Then I remembered the Caitanya-caritamrta chapter dealing with Srila Rupa Gosvami's dramas, Lalita-madhava and Vidagdha-madhava. When I turned to this reference, I found important dramatic works mentioned, specifically Bharata Muni's Natya-sastra, Rupa Gosvami's Nataka-candrika, and Visvanatha Kaviraja's Sahitya-darpana. At this time February 1984 1 went to India and acquired some books about Sanskrit drama. The more I read, the more convinced I became that I'd found the proper dramatic style to express our philosophy and the transcendental emotions we devotees feel.

One problem arose, however. In Sanskrit drama the hero cannot die, for then the play would end in an extremely painful, disconcerting way. The Sanskrit tradition never produced a formal tragedy, though a good case could be made that two dramas by Bhasa are tragic one about Karna and the other about Duryodhana. Since the Vedic view of life is not tragic, the final portion of a full-length Sanskrit drama should deal with the complete fulfillment of the hero's desires, which in Prabhupada's case was to die a glorious death. This posed a great problem for me because I wanted to dramatize Prabhupada's departure, but the tradition forbade concluding with the hero's death. Finally I decided to put aside writing the drama.

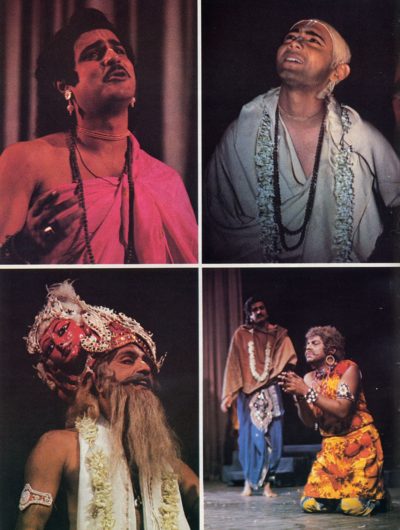

But by this time I'd read more than fifty Sanskrit dramas and textbooks on the subject, and I felt I should put that learning to good use. When I heard Bhakticaru Swami describe Lord Jagannatha's original appearance, I thought this might be an excellent theme for a drama. Using the Sanskrit tradition I had studied, I embarked on writing Jagannatha-priya Natakam The Drama of Lord Jagannatha. After completing that drama and gaining experience, I was able to write a second drama, entitled Prabhupada-bhakti-rasa, because I realized it would be possible to handle the theme of Prabhupada's final activities and departure while still maintaining the traditional dramatic rules.

BTG: It will be interesting to see how you did that, when the play is published. In what other respects are you guided by the Sanskrit dramatic rules?

TKG: The main purpose of drama is to convey rasa, or taste. That's the real intent of both the dramatist and the actors. Rupa Gosvami lists five primary rasas neutrality, servitude, friendship, parental affection, and conjugal love and seven secondary ones. Other rasacaryas, or rasa experts, have made slightly different categorizations. In any case, all the rasas an audience experiences, even dread and ghastliness, become a source of pleasure because of proper handling and aesthetic organization. Just as a dinner may have bitter and sour tastes, not just sweet ones, similarly a drama including elements of all the rasas becomes extremely satisfying to the viewer.

One rasa must dominate, the others merely assisting. Rasa is conveyed to the spectators via the emotions portrayed. The emotions that produce the main flavor of the play must be excited. Factors determining the emotions are the characters, natural expressions, fleeting sentiments, and associations (for example, the rainy season is associated with love). When the viewers grow increasingly aware of their enjoyment of the emotions, they taste the rasa, or flavor.

In my Jagannatha drama, vira-rasa, or chivalry, predominates. In the Prabhupada drama, karuna-rasa, or compassion, prevails.

The Jagannatha drama took the form of a nataka, the most extensive form of drama described by Bharata Muni. He lists ten main types of drama. The nataka is the most exalted, treating either chivalry or conjugal love in a full fashion. Since my second drama dealt with compassion, I looked for another form, but I concluded that Prabhupada's final pastimes required a full-length treatment. So even though the main rasa is compassion, I used the nataka form again.

This has a precedent in Bhavabhuti's Uttararama-carita, a very beautiful play depicting Lord Rama's lamentation after Srimati Sita-devi's departure. In an especially moving scene Rama returns to the forest where He was banished with Sita and recalls places they visited. Bhavabhuti rendered Sita as being under a spell, rather than as having disappeared into the earth, so she is able to be present with Rama invisibly. Seeing her beloved husband swooning with grief in separation from her, Sita also feels heart-breaking emotions. By her unseen touch she continually revives Rama, and the audience, seeing them lament and hearing their dialogue of warm reminiscences, experiences karuna-bhakti-rasa, the height of the emotion of compassion.

BTG: Since the Sanskrit tradition includes many kinds of fine literature and philosophy, why are you concentrating on drama to get your message across?

TKG: Scholars within the Sanksrit tradition consider drama to be the most complete artistic form. Bharata Muni not only defines the laws governing ideal literary creation but precisely delineates how each work of dramatic literature should be performed. The combination of literature, musical performance, and visual representation makes the dramatic art a rich and powerful source of both delight and instruction. Gary A Tubb, the chairman of the department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies at Harvard University, discusses the value of creative literature to convey philosophical truths in his foreword to my book Jagannatha-priya Natakam. I'll read you part of his comments:

Of course, there are works of other types that also intend to instruct us and that may seem to do so more directly. The most famous explanation of differences in how these works operate is given by Abhinavagupta, the author of an influential commentary on the Natya-sastra. The authoritative scriptures, he said, educate us in a very straightforward way, after the fashion of a master, by giving us unequivocal commands. And the works of traditional history edify us more gently, after the fashion of a thoughtful friend, by putting before us examples of the actions of others in the past and of what fruits befell those actions. But the works of fine literature instruct us in the most irresistible way, after the fashion of someone we love, by giving us so much joy that we are scarcely aware of an underlying purpose.

BTG: You already mentioned Rupa Gosvami, an important figure in the modern Vaisnava tradition. Of what special usefulness is the theater to devotees of Krsna?

TKG: Rupa Gosvami was learned in the Natya-sastra and other ancient manuals of aesthetics and used the concepts of classical dramaturgy to explain the Vaisnava system of the five main rasas as moods of religious emotion. He illustrated those religious feelings in his dramatic compositions.

A Vaisnava's entire life should be a religious experience. But since life must embody all types of emotional experiences to be satisfying, the dramatist tries to lead the audience to experience emotions in the most purified way. The aesthetic organization he gives to emotions heightens and purifies the audience's experience of them.

Prabhupada writes in The Nectar of Devotion, a study of Rupa Gosvami's Bhakti-rasamrta-sindhu, "Whenever there is a recitation of poetry or a dramatic play on the different pastimes of Krsna, the audience develops different kinds of transcendental loving service for the Lord. They enjoy different types of ecstatic loving sentiments."

Traditionally, dramas were performed on special occasions such as religious festivals. Very often they were performed next to temples. Although it would be incorrect to say that drama was meant to be an integral part of the religious ritual, it was meant to be a supplementary part-less formal than the actual temple worship, but just as meaningful because it conveyed in a very pleasant way the same religious and philosophical message.

BTG: What about varied arts such as Bharata Natyam and Kathakali, which we sometimes see performed in the West, or the contemporary theaters in India?

TKG: All the ethnic traditions are rooted in the Sanskrit tradition, so you'll find that Kathakali, Bharata Natyam, and the Odissi dance forms, among others, all have their basis in Natya-sastra. They have just emphasized the dance and musical aspects rather than the spoken line, although certainly they convey the same themes.

Today in India, because of mass communications and regular contact with the West, interest in Western-style drama is increasing. Major cities have groups that stage not only Shakespeare and the more modern playwrights but even the works of living Western dramatists, including musicals. And since India is always rife with political and social disputes, the theaters often express those themes. Probably Rabindranath Tagore was one of the first playwrights to do this. So there are tendencies to move away from Sanskrit classical drama, including many regional theaters working in regional languages.

BTG: Srila Prabhupada once wrote an encouraging letter to a devotee-actor, saying that Lord Krsna would direct him so that one day he would be acting dramas about Krsna on Broadway. Any comment?

TKG: Prabhupada said that the purpose of all art is to please Krsna. So, if while pleasing Krsna we also reach Broadway, that will be our success. Prabhupada had very high expectations for dramatic performances and saw them as a means to communicate the philosophy of Krsna consciousness to people throughout the world. He considered drama one of the main methods to achieve what he termed a "cultural conquest."

Ultimately, the test of a good drama must be its performance. I've already seen, after the premiere of my Jagannatha drama in Mayapur and later in Calcutta, that the public takes very well to it. One theater critic wrote in his review, "The evocative and poetic language of the drama is a treat to the ears."

I'd like to see drama troupes spring up throughout the Hare Krsna movement. The most effective thing would be for local theater groups in each country to address audiences in their native languages. What's needed to bring this about, of course, are good scripts. Without a full repertoire, what's the inducement for such troupes to form? So, from my side, I'm trying to provide worthwhile material, and I hope it will inspire more and more of our members to take part in dramatic performances.