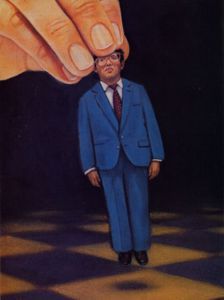

Are we pawns in the hands of fate,

architects of our own fortune, or both?

James Oliver Huberty was a pent-up, out-of-work gun nut with a grudge against the world. Finally he snapped. One day last July, Huberty armed himself and went "hunting humans." Storming into a McDonald's restaurant in San Ysidro, California, he opened fire. By the time a police marksman dropped him seventy-five minutes later, he had killed twenty-one people and wounded eighteen others. News of Huberty's rampage shocked the nation. It was the worst one-day, one-man massacre in U.S. history. For days afterward, across America, the golden arches symbol of the McDonald's restaurants stood as a grim reminder of the tragedy in San Ysidro.

The morning after the massacre, three passengers seated near me on a train into Philadelphia were discussing the incident. One of them defended Huberty, saying he had been a victim of circumstances beyond his control, "a pawn in the hands of fate." It had been his destiny to kill. The other two disagreed. Huberty, they said, had had the freedom to do otherwise. He didn't have to commit murder. Both sides were giving reasons to support their views. Before I could decide whether to break into their conversation, however, all three got off the train, leaving me to ponder over this problem and to reflect on the Krsna conscious solution.

The philosophical question of fate versus free will is an old one. Are our thoughts and actions completely determined by forces over which we have no control? Or, are we free to decide for ourselves, to be the captains of our fate? Most of us are inclined to think we are free. The idea that our subjective sense of choice might be illusory, we find hard to accept. It goes against the grain of our instinctive consciousness, against our sense of human dignity, and against our sense of morality. Nevertheless, there is strong evidence in favor of determinism, and the question of fate versus free will remains a controversial issue.

Many theories, along with their various supporting arguments, exist in favor of both free will and determinism. Consider determinism. For hundreds of years, the main argument in favor of this view was religious. God, being all-powerful and all-knowing, was considered to have predetermined all that would happen in the future. He knew every choice we would ever make. Everything, therefore, must be predetermined by His prior knowledge and prior decisions.

Another argument for determinism, called the metaphysical argument, is based on the maxim "Every event must have a cause." The idea here is that inasmuch as the belief is widely held that all physical events must have a cause, there is no justifiable reason why the same should not apply to mental events. Acceptance of physical determinism and rejection of mental determinism would be arbitrary. For one who accepts this maxim, it stands to reason that determinism is irrefutable.

In the modern day, however, the strongest argument in favor of determinism comes from science. Discoveries in the fields of psychology, physiology, neurology, and pharmacology indicate that the determinist's dream of being able to predict all facets of human behavior may soon come true. Behavioral scientists anticipate a time when an examination of the biological and psychological characteristics of an infant will enable them to write his life's story before he lives it. In short, the evidence available today regarding human motivation and how human attitudes are affected makes a strong case for determinism.

Still others argue in favor of free will. William James, in his essay "The Dilemma of Determinism," points out that we undeniably have attitudes and experiences that make sense only if we are free agents. For example, our feelings of regret or remorse make no sense if our lives are strictly determined. Determinism puts us in a "curious logical predicament," James writes, wherein murder and other heinous acts are no longer sinful or immoral and regret for things we have done becomes an absurdity and an error. For what is the use of regret or remorse if abominable acts absolutely cannot be avoided?

Apart from feelings of remorse and regret being meaningless, legal and ethical judgments also become meaningless, James points out. As Huberty's protagonist on the train was arguing, we cannot attribute responsibility to criminals for their crimes if they have no choice. If we are merely pawns in the hands of fate, how can we be punishable for doing what we couldn't possibly have avoided? If we say, "Well, punishment is also predetermined," then punishment loses all moral significance, If we then claim that punishment is useful because it can alter the factors that determine a criminal's behavior, then we must assume the judges are free agents in their decision to punish. This simply proves that for morality to be meaningful, someone must be assumed free.

Finally, an argument that is sometimes made in favor of free will is that if determinism is true, those who believe in free will are determined to be that way. In that case, what is the use of discussing fate and free will? Discussion implies freedom to decide the matter one way or the other. The very fact that determinists bother to argue the question shows their implicit acceptance that some free will exists. Or they must agree that they have been engaged by fate to waste their time arguing, another "curious logical predicament."

The Krsna consciousness philosophy, I'm happy to say, can reconcile the two poles of the fate-and-free-will controversy. This may startle some of our readers. Generally, those who have only a cursory knowledge of the Krsna conscious philosophical system assume it is deterministic, because it embraces the idea of karma. According to the popular conception of the law of karma, all human actions are the result of some previous action. This is clearly a deterministic concept. Naturally, therefore, some of our readers may wonder where free will fits into the Krsna conscious scheme.

We get our understanding of the reconciliation between fate and free will from the Bhagavad-gita. The first relevant bit of information given in the Gita is that we are not our material bodies; we are eternal spirit souls who occupy material bodies. Once this is at least theoretically accepted, we can go on to understand the extent to which we are determined and the extent to which we have free will.

As spiritual beings, we are all part and parcel of the original and supreme spiritual person, God. That means we are qualitatively of the same nature as God. Just as a tiny gold nugget contains, in minute degree, all the chemical properties of the huge gold mine, so we, the individual spiritual entities, have all the spiritual qualities of God in minute quantity. Qualitatively we are one with God, but quantitatively we are not. God is infinite, and we are infinitesimal. We can never be equal to Him.

The Bhagavad-gita informs us that God's identity is Krsna. He is the possessor of all opulences wealth, beauty, knowledge, strength, fame, and renunciation without limit. We, being part and parcel of Him, have these same opulences, but to a far lesser degree. God is the supreme creator, and we too have some creative ability. God is the supreme independent person, and we too have minute independence, or free will. Because of our finite nature, however, our natural condition is to be dependent on God. In other words, although we have free will, still, because of our minuteness, our highest beatitude is to be sheltered and controlled by God. Our minute free will is manifest, however, in the form of our prerogative to choose between staying under Krsna's control in the spiritual world, His abode, or coming to the material world and trying to enjoy apart from Krsna.

Krsna creates the material world to facilitate those souls who choose to leave the spiritual world. Since the material sense objects and our spiritual senses do not interact, material nature awards us material bodies equipped with material senses so we can try to lord it over nature and enjoy. At the same time, nature conditions us to forget our original identity and characteristics. This condition is called maya, illusion. Because of this illusion, we try our utmost to squeeze out pleasure and happiness from this material world.

Actually, we cannot control the material energy of God. Our material bodies are mechanisms produced by nature and are completely subject to the laws governing matter. All we are free to do is desire according to our conceptions of material enjoyment. And the material nature, acting as God's agent, fulfills our desires. Bewildered by our misidentification with the body as our true self, we foolishly think ourselves the doers of activities in this world. In actuality these activities are carried out by the material nature as conducted by its three modes: goodness, passion, and ignorance.

Goodness, passion, and ignorance are the three phases in which material nature operates. A person in the mode of goodness is wiser than persons in the other modes. He has greater knowledge and is less affected by the material miseries. He likes clean surroundings and has few vices. The representative type of this mode is the poet or philosopher.

The mode of passion is symptomized by attraction between male and female. This attraction leads to intense longings for sense gratification and motivates one to seek honor in society, acquire many possessions, and become entangled in family affairs. A person in the mode of passion must struggle and work very hard to please his spouse and maintain his prestige. In the modern day, the mode of passion is considered the standard of happiness. Everyone feverishly tries to enjoy his senses at virtually any cost, the net result being greater and greater illusion. Gradually the illusion becomes so deep that the mode of passion is transformed into the mode of ignorance.

The mode of ignorance is the opposite of the mode of goodness. A person in this mode is degraded to the lowest status of human life, and even lower, into the animal species. His intelligence becomes so covered that he loses all interest in cultivating knowledge. He is unclean, lazy, and dull. He is not interested in spiritual understanding; rather, he is addicted to intoxication and too much sleep. Such unfortunate persons populate the skid rows of the world. They are virtually unable to do anything to benefit themselves. Ultimately the mode of ignorance leads to madness.

In the Bhagavad-gita, Krsna explains how every activity in this material world is associated with one of these three modes. For example, there is faith in the mode of goodness, in the mode of passion, and in the mode of ignorance. The same is true of food, knowledge, acts of charity, work, understanding, determination, and even happiness. At every moment our bodies are under the influence of these modes. When we sleep or take intoxicants, that's the mode of ignorance. When we indulge in sex, that's the mode of passion. And when we philosophize about life's meaning, that's the mode of goodness.

Whenever we choose a particular course of action in terms of our desire for material enjoyment, we are in fact agreeing, knowingly or unknowingly, to become influenced by the mode associated with that particular choice. In other words, our free will in this material world is limited only to choices within the modes of nature. In our original condition we are transcendental to these modes, but upon coming to this material world, we lose our freedom to act outside of their influence.

Material nature, although allowing us only a limited choice, deludes us into thinking we are completely free. But our freedom is like that of a prisoner who has the privilege to choose between a first-, second-, or third-class prison cell. He has three choices, but in all cases he is still in prison. Like a prison, the three modes of nature restrict our original free will. The instinctive sense of free will that we now feel is factual, but it is only partially realized.

Our destiny in this material world is determined by a combination of our partial free will and the three modes of material nature. According to our previous karma, we are destined to face certain situations in this life. In those situations we have a certain amount of freedom to choose how we want to react. Once we choose, we come under the control of the mode associated with our choice, and we are obliged to accept the consequences, be they happy or miserable.

Huberty, for example, was destined to lose his job and to have a generally hard life. He reacted to all this by going beserk and killing, which is in the mode of ignorance. He could have slept it off, or he could have sought help through religion, or even psychiatry. But blinded by his frustrated desire to lord it over the material world, he came under the influence of the mode of passion, which later became transformed into wrath (ignorance). Then he was locked in. He felt compelled to go hunting humans. In his heart he knew better, but he could not surmount the conditioning influence of the mode of ignorance.

Conditioning by the modes of nature is so strong that we tend to make the same choices again and again, even when we know our choice is detrimental to our long-range self-interest. This conditioning also accounts for why determinists are able to gather so much scientific data in support of their theory. As we all know, force of habit is extremely difficult to break. We have our partial free will, but even then we become so conditioned that our partial free will is scarcely used. We just make the same choices again and again. Thus. for a given set of circumstances our choices and actions become predictable.

Fate and free will, as described in the Bhagavad-gita, are analogous to the relationship between the state, the law-abiding citizen, and the criminals in prison. A citizen is considered free only if he obeys the laws of the state. If he breaks the law, he goes to jail. A prisoner may enjoy limited freedom to choose between reading a book or writing a letter: between Jell-0 or ice-cream for dessert; between work in the barber shop or in the kitchen. But he is not free to abandon the prison altogether. By comparison, the free citizen is in a better position, but both are controlled by the law. Practically, the only unconditioned exercise of their free will is in their decision to choose between being a good citizen or a criminal.

Similarly, as eternal spirit souls, we are forever free to choose between being a free citizen of the spiritual world or an imprisoned citizen in the material world. The choice is entirely up to us. In the spiritual world we voluntarily agree to be controlled by Krsna, in love. As a result, we relish perpetual transcendental bliss in the association of the pure devotees of God. In the material world we are controlled by Krsna also, but through His agent material nature in the form of the three modes. Here we must undergo repeated birth, old age, disease, and death, as well as other concomitant physical and mental miseries.

From the above description, it is clear that Huberty was responsible for his shooting spree. After all, he chose to come to the material world, and of all possible choices, he made the decision that obliged him to mow down twenty-one people. He could have done otherwise, but he didn't.

Furthermore, we can understand that in spite of the law of karma, moral and legal judgments are still relevant, because we do have some limited choice to react morally or immorally to the various situations we encounter due to our past karma. And because we have choices, our feelings of regret and remorse are also valid.

Please note, however, that from a purely spiritual point of view, the exercise of our limited free will in this material world is of relatively little significance. It simply isn't our natural position to be here in the first place. A liberated soul, a free citizen of the spiritual world, understands that all aspects of life in the material world whether in goodness, passion, or ignorance, whether moral or immoral are unnatural and undesirable for the soul.

The Bhagavad-gita further informs us that we need not remain here; we can be liberated. By proper understanding of our spiritual position, the nature of this material world, the nature of the spiritual world, and the nature of Krsna, we can become enlightened and free from entanglement in the three modes of nature.

We can gain this understanding by a careful study of the Bhagavad-gita As It Is. There the process of liberation, called bhakti-yoga, the path of pure devotional service, is also given. Devotional service is transcendental to the stringent rule of the three modes of nature. The decision to perform devotional service is, therefore, the best use of our free will. Similarly, your reading BACK TO GODHEAD magazine is a liberating, devotional activity. It is not under the jurisdiction of nature's modes. It is an act of your original free will.