"The elephant gets his hundred pounds, the ant his grain.

Only man has an economic problem."

"God made the country and man made the city," wrote the poet Cowper. And as one journalist remarked, "The Devil made the small town."

Or so it seemed to us a couple of years ago here in deepest Pennsylvania. At the Lions Club's annual fall parade, a local church had depicted the open sepulcher of the "RISEN SAVIOR" next to three grave markers: one for Buddha, one for Mohammed, and one for Krsna. The float had placed first, the newspaper ran a photo, and since we've yet to see a Buddhist or Mohammedan out here, the picture spoke to us like a punch in the nose.

Rascals! Krsna is the Supreme Personality of Godhead. He never dies. That's ignorance! Besides, why glorify Christ at others' expense. Call the minister!

The reverend was apologetic. Against his advice, some ladies in the church had gone ahead and arranged for the float. He confessed "pastoral neglect."

Call the newspaper!

The editor was frank: "I knew you people weren't at the parade, so I didn't think you'd notice the picture. Write us a letter and well print it."

A lively exchange of letters ensued, selling out the county paper for weeks. As Thanksgiving approached, we raised the issue of meat-eating: "Can you picture gentle Jesus the emblem of compassion patronizing a slaughterhouse?"

The reply really threw us. From the ox roast to the turkey shoot, from the meat house to the chicken factory, from the flower-scented valleys to the stony wooded hills (where workers and schoolboys were let out to hunt deer), came the resounding "YES!"

It was then and there we resolved to give our neighbors Food for Life.

Hare Krsna Food for Life, like other food distribution programs, arose in the cities to meet the challenge of poverty amidst plenty. By 1983 some 30 million Americans were living at or below the poverty line; about one of every eight able and willing to work was out of a job; and two to three million wandered the streets, homeless and hungry.

By God's natural arrangement, no creature in the jungle starves the elephant gets his hundred pounds, the ant his grain. Only modern man has an economic problem. Rising hunger amidst rising surpluses the ultimate mismanagement.

The politicians were embarrassed, but ISKCON especially with its expanding network of temples, restaurants, and dairy farms was ready. Between 1983 and 1986 Food for Life centers sprang up in most major cities throughout the United States and Canada. Good food, too. Freshly baked bread, piping hot curries and casseroles, crisp green salads, fruit and yogurt drinks, delicious Indian desserts this was no crumbs for bums. What's more, it was prasadam, Krsna's mercy, a sumptuous sacrament which, the devotees knew, could arouse one's dormant, natural love for God. The devotees' enthusiasm, therefore, was boundless.

And the politicians took notice. "They can take $15,000 and do what the average food program does with $75,000 or $100,000," said a Cleveland City Councilman. "It's because of how they cook it."

Grants at the federal, state, and local levels; donations of United States Department of Agriculture surplus foodstuffs; and access to private food banks helped Food for Life expand throughout North America and beyond. Besides ISKCON's ongoing work in India (over 12 million meals served to date), Food for Life now reaches the needy in Peru, Bolivia, Spain, France, the Philippines, Australia, Nigeria, Kenya, and remote villages in South Africa. The program seems to grow with the hunger. As one Australian clergyman put it: "Hare Krsna, I think, will be the Salvation Army of the twenty-first century."

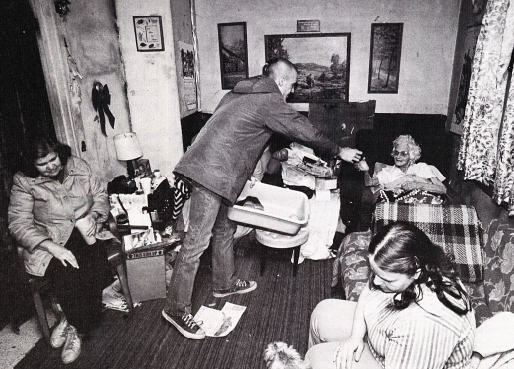

Just a few hours' drive from us, ISKCON of Philadelphia's Food for Life program is already filling that role. Begun in 1983, the program currently feeds up to 1,500 people a week. An on-site shelter handles twenty-five homeless men nightly, offering them psychological help and job counseling. The program has a $100,000 annual budget funded by grants from the federal and city governments and Traveler's Aid. Aproposed new shelter for 100 women and children would boost the budget to $500,000, and welfare officials, noting the devotees' skill in helping the needy, are enthusiastic.

In February 1985, encouraged by the devotees' success in the big city, we completed plans to bring Food for Life to the hinterland. We had a good field. The two counties nearest our farm were filled with old-timers, many of them sick, disabled, or struggling on a fixed income. Illiteracy and unemployment were well above the national average. And with that float winning first prize, God knows we needed the public relations.

ISKCON Philadelphia's Food For Life Program

A cornucopia decorated our first newspaper ad. "FOOD FOR LIFE. Free Hot Meals Delivered To Your Door. Monday, Wednesday, Friday. All Wholesome Farm Fresh Produce And Milk Products. Sponsored By ISKCON Farm. Call 527-4101."

Mary Catherine Campbell was the first to call. We drove out to Lewistown to make the delivery and found a sweet little old black lady with a heart condition and crippling arthritis.

"I'm not black, honey, I'm colored. The Lord has many flowers in His garden. Now be a good boy and open this jar for me, would you?"

The steaming vegetables, the fresh bread and butter, the salad from the garden, the fruit from the orchard, the homemade cookies Mary loved every bite and told all her friends. By month's end we were serving a half dozen other folks in her apartment building. And more were calling. A shut-in with terminal cancer; a pregnant mother with cerebral palsy; a little girl's divorced father who hurt his back at work, a widow who ran a kennel with her retarded son. People who had never heard of Krsna before were flocking to His Food for Life, and each new tale of suffering told us to get cooking.

By summer we were serving seventy-five people, and the community was taking notice. The newspaper ran a front-page story. The hospital started referring outpatients to us. A radio reporter hopped in our van now emblazoned with a Food for Life logo and did a sixty second news spot. Even the laconic old farmers, the guys with the bandanas and Casey Jones hats, were giving us the thumbs-up. They weren't sure what we believed, but they sure believed in our food.

A year had passed: 13,000 meals served, and the count was rising. To help defray the costs of the program, we tapped into a Harrisburg area food bank, but all they could offer us was Planter's Peanuts and Hawaiian Punch. We turned to the USDA. In the cities, USDA surplus regularly contributes bulk foodstuffs like butter, flour, and cheese to Hare Krsna Food for Life. At any time, government inspectors may come to a central distribution site and see the obvious need of the recipients. The people on our country-style program, though, were somewhat hidden. Wary of invading people's privacy, government officials left it to us to prove our recipients' need, so in May 1986 we did a survey The results:

1. Fifteen percent of our recipients were practically illiterate and couldn't fill out the questionnaire by themselves.

2. Fifty-five percent reported serious handicaps in their household.

3. Eighty-eight percent were at or below the poverty line.

Those figures qualified us to receive USDA surplus, but even more heartening were the people's answers to the survey question How has Food for Life helped you? Some replies:

"I is near blind. I is mental retarded. I has diabetes. Fresh fruit and salads helps me."

"Bone disease in legs. My food stamps don't go far enough. The boys are very nice and polite. They don't make you feel small because you get help."

"Epilepsy. Sometimes we don't have any food and Food for Life helps us to stay alive. We like the boys for being themselves. Thank you for being yourselves everybody."

"Helps with meals between checks. They can bring a hundred dollar bill if they like."

"Diabetes. High blood pressure. Arthritis. Since receiving food from ISKCON farm, we have been relieved of the anxiety of not having enough to eat. Thanks for the food and for the care shown the recipients. And may God bless you."

Encouraged by the survey (and the warming weather), we decided to do something we'd never dared. Take off our hats. The shaved head, respected in India, usually shook heads in America and out here in the woods, the lock of hair on top would make a pretty bull's eye. Yet Sri Caitanya had said that a devotee is one who, when seen, reminds one of Krsna. Simply by seeing us, people should remember who was providing everyone's food for life. The shaved head and the tilaka* [*Sacred clay marking the body as a temple of God.] decorating the forehead were the timeless trademarks of Krsna's devotee. Would folks mistake tilaka for the mark of the beast?

Only one old jezebel canceled. The rest of our recipients didn't mind at all. Not after having eaten so much prasadam. Oh, they blinked at first, and some of the kids made fun. But prasadam had touched their hearts. Anyone who gave away food like this must be God-sent. We were their friends. To some, their ministers.

As I write, we're serving 150 people thrice weekly over a hundred-mile route. At 7 A.M. Caitanya dasa starts the cooking in the temple kitchen. The main course today: spaghetti and kofta balls.** [**Deep-fried vegetable-and-batter balls in tomato sauce.]

Many nutrition experts call the Hare Krsna diet one of the healthiest in the world because its selection of lactovegetarian foods contains the most important and basic nutrients. Millions of people are hungry, and millions more are overfed but undernourished. But a properly balanced vegetarian diet easily provides higher-quality protein than a nonvegetarian one and at much less cost.

Caitanya dasa cleans as he works. "Cleanliness is next to godliness," he says with a smile. He prepares, spices, and cooks the food to bring out the maximum in taste and nutrition. And like all good devotee cooks, he knows that the most important element in preparation, in serving, and in offering is to act with love for Krsna.

By 11:30 Graham, Bill, and I are rolling off in the van, anticipating the day's deliveries. Over the river and through the woods to Grandmother Ruth's we go.

Ruth says she was sorry to read that our farm's cow sign was stolen. "I know who done it," she confides. "My nephew. That boy shames me."

Ruth loves Food for Life, but sometimes her hearing confounds us.

Ruth: How much do I owe you for the strawberries?

Bill: They're free.

Ruth: Three? Three dollars for a cup of strawberries?

Bill: No, free! Did you think we were going to make you buy them?

Ruth: What? And I have to divide them! Three dollars and I have to divide them! Food for laughs. But the next stop always sobers us. Mountains of debris, poor sanitation, contaminated water, faulty diets, poorly heated and overcrowded houses. The Other America. Sign on the Eby's door: THIS HOUSE GUARDED BY SHOTGUN THREE DAYS A WEEK YOU GUESS WHICH THREE.

"My husband loves your Hindu spaghetti," says Mrs. Eby.

Mr. Eby is out of sight, embarrassed but grateful we're putting food on his table. The Ebys could never afford the school lunch for their kids, whose classmates made fun of the meager grub they brought from home. Now their kids bring Food for Life to school, and their prasadam treats are the envy of the lunchroom.

Alvin Mumma has been blind for sixteen years, and wife Lucy is blind in one eye from crippling arthritis. Surviving on Social Security, the Mummas of McAlisterville live in a tumble-down trailer with their grown son Harold.

Harold is a bona fide prasadam addict. All of our McAlisterville recipients called us because Harold told them about prasadam. The first time we served kofta balls with the spaghetti, Harold went wild. After eating his and his parents' portions, he cycled around town and ate five servings delivered to his neighbors. That made a gallon.

Prasadam changes people. One McAlisterville lady was spreading rumors that we kidnapped kids and made them work on our farm. We had lots of cats and dogs on our farm, she said, so we ground them up and threw them into the food. But when she tasted some prasadam that Harold had slipped her, she called us that night to sign up.

Another recipient used to threaten us. He said he found twigs and glass in the food; said he cut his mouth up and had to go to the hospital; showed us an old salad he said had made his daughter sick; said he would get his deer rifle out after us if we came back. His mother said he wasn't "wrapped too tight," so we didn't. A month later he called and begged us to come back. Life without prasadam was just too painful; today, he is our most respectful recipient.

Autumn leaves lighten the road to Lewistown. An old man rides a bicycle with baskets full of cans; another rummages a barrel for salvage. Past a golden canopy, the big valley spreads its farmlands wide. Harvest colors glisten in the sunshine, cumulus castles sail the blue. Poverty amidst plenty is doubly absurd in the country, the home of health and abundance. Who but a savage would kill or eat an animal when the earth has plenty in store? Clean air, fresh water, peace of mind you can't buy these gifts in town. Yet most of our recipients live in these bleak industrial backwaters. They strew the valley like litter. Nature's fine: hunger, disease, despair.

Old Mr. Young sits on his porch reading one of our books. He likes prasadam almost as much as his dog, Babe, does. As soon as Babe sees the van coming, he starts roaring and dancing and wagging his tail. I toss him a bun. He leaps, catches it in midair, and has already swallowed once by the time he touches ground. He eats cookies faster.

The Starr's porch is caving in. Food for Life button clacking against my suspender buckle, I bound up the steps, knock, and (to the tune of "London Bridge is Falling Down") sing: "Hare Krsna Food for Life…."

And from inside: "Food for Life, Food for Life," and ten people roar with laughter. Mrs. Starr flings open the door. "Where's Grambo? Jane wants to learn that swami dance. Anyway, come on in."

Family members are draped everywhere. Puppies play in a pile of trash. Over the table where I set the prasadam, a fly swatter hangs from a cross. Little Bobby shoots me an obscene gesture. "I hate your damn food."

"He's mean since he broke his wrist," says Mrs. Starr, flushing. "Bobby, I want you to apologize to the man, right now."

Bobby says he's sorry and I sign his cast.

By three o'clock we're nearing the end of the line. And so are many of the old folks at Burgard Apartments and Lawler Place. Recipients here have worked hard all their lives, are more or less disabled, and now live alone on food stamps and Social Security. Their altar is the television. But a human being is meant to die thinking of God, not some sap on the soaps. Our alert recipients agree.

Mary Catherine Campbell has just returned from the hospital with a new hip. She now has six replacements in her hips, shoulders, and knees.

"They'll never replace you, Mary." "Oh, goodness gracious!" she laughs. "Only the Lord can do that." Then: "Open this letter for me, would you, Honey? Somebody slipped it under my door last night."

I open the letter and see a violent scrawl. Mary asks me to read it aloud.

"You black bitch, you been getting too much free stuff. You better work for what you get."

"THE NERVE!" The hurt in Mary's eyes turns to pity. "Anyone with that much hate inside must really be suffering. Anyway, I can't be losing sleep over it. Just leave me a salad today, Honey."

"Okay, Mary." I want to say more. Next time. "See you Friday."

"Lord willing."

Dante Molinari likes his meals unsalted. He walks with an eagle's-head cane he picked up for ten bucks at the VFW. His favorite World War II memory is pulling up to the Rhine with General Patton a week after D-day and urinating "in Hitler's backyard." Close your eyes and he's George Burns.

"The day the stock market crashed I was standing on a corner with a cop. I was a kid, a Wall Street runner. All of a sudden people started jumping out windows. I said, 'Murphy, you gotta do something He said, 'There ain't nothin' I can do.' What a mess! But my father, he didn't jump out a no window. He said, 'The good Lord will take care of us. And He did."

And at last the Sassamans. Mr. Sassaman, the image of Santa Claus, repairs lawnmowers and moonlights as a butcher's helper. He loves prasadam and says, "Hare Kwithna." But at his door today, Graham hears a stranger's voice inside.

"I'm telling you, Mr. Sassaman, they're a cult, and their food is fit for the Devil." "Then how come, whenever I go to church, all they want is money? But these people never ask me a penny for their food. It's good food, and they're good people."

"Food for Life!" Graham walks in and sets the food on the table.

The stranger's voice loudens. "I'm gonna tell him to his face. Son, you belong to a cult!"

"So did Christians till they got some political clout."

"Lord, save this boy!"

"Save yourself and eat up," says Sassaman. "This food's mighty good." "Thanks, Mr. Sassaman."

"Hare Kwithna."

Back at the farm, our kids charge the van for leftovers. We served our thirty thousandth meal today, and the kids say that two new families called up while we were out. I smile and wonder what those church ladies are thinking about us. It was the Supreme Lord Himself who inspired that float, for strange and wonderful are His ways. And His prasadam is out of this world.

"No One Should Go Hungry"

Mukunda Goswami director of Hare Krsna Food for Life,

explain the spiritual significance of prasadam distribution.

Profuse distribution of prasadam vegetarian food offered to krsna is integral to the Hare Krsna movement Srila Prabhupada writes in his commentary on the Caitanya-caritamrta:

In the Hare Krsna movement the chanting of the Hare Krsna maha-mantra, the dancing in ecstasy and the eating of remnents of food to the Lord are very important. One may be illiterate or incapable of understanding the philosophy, but if he partakes of these three items, he will certainly be liberated without delay.

Elsewhere in the Caitanya-caritamrta Srila prabhupada explains. "actually, by eating such maha-prasadam one is freed of all the contaminations of the material condition."

Commenting on a great festival held by the saint Madhavendra Puri at Govardhana Hill in India, Srila Prabhupada explains that all the food m Govardhana Village was offered to the deity of Gopala and then distributed to everyone.

They brought all the food they had in stock, and they came before the Deity not only to accept prasada for themselves, but to distribute it to others. The Krsna consciousness movement vigorously approves this practice of preparing food, offering it to the Deity, and distibuting it to the general population. This activity should he extended universally….

Giving prasadam specifically to the poor is also an important theme in Vedic literature, the Srimad-Bhagavatam glorifies King Rantideva, who, at the point of breaking a foty-eight-day fast, fed two beggars the very food he was about to eat. Srila Prabhupada explains this selfless quality thus:

A Vaisnava [devotee of Krsna] is therefore described as being … very much aggrieved by the suffering of others. As such, a Vaisnava engages in activities for the real welfare of human society.

In India in the early seventies Srila Prabhupada began ISKCON Food Relief (IFR). One of his mandates for the project was that "no one within ten miles of the temple should go hungry." A big task. IFR grew and fed vast numbers of India poor, but went largely unnoticed in the West.

Hare Krsna food for life was born out of two needs: first to extend the IFR concept to the west and second, to dispel certain misconceptions about the Hare Krsna movement. (In the United States, a stereotypical perception of devotees frequently surfaced. We were street chanters, airport solicitors, "cultists," or religious zealots crusading for a kind of salvation that was foreign, even suspect to the Judeo-Christian tradition.) It was important that Western society understand devotees as Vaisnavas, people who care deeply about others and who show that care though their actions.

In the West even though many original precepts and practices of the Judeo-Christian tradition are no longer extant, "religious charity" is still a widely supported phenomenon. We knew we would achieve greater public understanding by extending our many existing prasadam distribution programs to reach the hungry and destitute. ISKCON's Public Affairs Ministry decided to name the program "Hare Krsna Food for Life," remembering that Krsna is the essence of all life and that all the food would be prepared for the pleasure of Krsna

We began in 1982 with a small booth from which devotees fed 150 hungry and homeless people three days a week in downtown San Diego's Horton Plaza. Within five years the program had spanned the globe and is now active in dozens of cities worldwide. Substantial government and private donations of food, money, and other items for the program were significant signs of approval by the establishment.

In a few years Hare Krsna Food for Life had, in many regions of the world, dramitically improved the public's perception of the movement. On May 29, 1985, Mayor Goode of Philadelphia delivered the keynote address at the grand opening of that city's Hare Krsna Food for Life shelter, heralding a new development in the program's growth shelters for the homeless. A second shelter about to open in Philadelphia will house one hundred homeless women and children.

Currently Hare Krsna Food for Life programs interface with programs for animal rights and with vegetarian groups throughout the world. Hare Krsna Food for Life regularly participates in such annual events as the Great American Meatout in the United States and the protest staged against Italy's hunting law on the first day of Italy's hunting season. Future plans include more networking with vegetarian groups, animal rights groups, and hunger-relief and shelter groups around the world, the launching of culinary and nutritional instruction programs for the needy, and more shelters for the homeless.