Breathless, six-year-old Manjunath bursts into the courtyard of his house. “Ma, the Hare Krishnas have arrived! I’m going to them.”

Without waiting for his mother’s reply, he rushes out into the street, where a group of men dressed in dhotis and kurtas are chanting Hare Krishna and dancing in joy. Manjunath eagerly joins the dancing party. As the group passes through the streets of Ambiste, a nondescript village in Maharashtra, Manjunath calls out to his friends, and they join in.

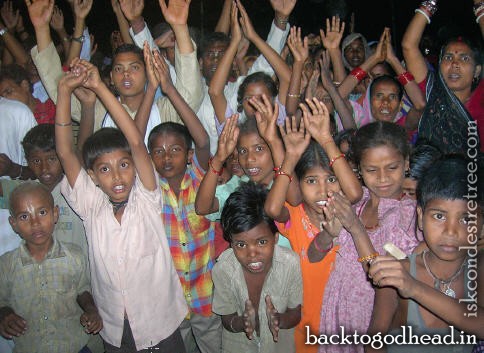

Women, their faces half covered by saris, peek out at the scene and then smile to each other; men nod and clap their hands. The group moves on till it reaches the festival site, the grounds of the primary school. The crowd, which began with fifty kids, now includes more than two hundred adults.

A short, stocky man in saffron robes, who has been leading the chanting, turns to them and smiles.

“Welcome to the Hare Krishna festival!”

Inspired by a Traveling Preacher

“For a long time I dreamt of spreading Krishna consciousness in the villages of Maharashtra,” says Rupa Raghunatha Dasa.

Born in rural Maharashtra, as a young man he studied in Mumbai while living in an ISKCON hostel for students.

“After I completed college,” he says, “I decided to dedicate my life to Srila Prabhupada’s mission and join the movement as a full-time devotee.”

After an initial stint at ISKCON Belgaum, Karnataka, he joined the ISKCON temple in Chowpatty, Mumbai, as the head priest, a service he performed for more than ten years. When many new devotees wanted to engage in deity worship, Rupa Raghunatha was asked to take up the leadership of the traveling book-distribution party.

“I was devastated,” Rupa Raghunatha recalls. “I was so attached to deity worship that to even think of doing anything else was heartbreaking. For days and days I sulked and cried, unwilling to leave. The temple leaders then took me to my spiritual master, His Holiness Radhanatha Swami Maharaja, who inspired me to spread the teachings of Lord Caitanya by traveling and distributing books.”

For the next three years Rupa Raghunatha traveled the length and breadth of India. Under his leadership the bus party was instrumental in distributing more than sixty thousand Back to Godhead magazines at the 2003 Nasik Kumbha-mela, a festival held once every twelve years and attended by millions.

“The days of book distribution were very inspiring for me,” he reminisces. “We were completely dependent on the mercy of the Lord. There were situations when we had no one to help and save us, but somehow by God’s grace we were always protected.”

But Rupa Raghunatha wanted to do more.

“In India, ISKCON has an image as an urban organization with a membership restricted to the rich and educated,” he says. “But seventy percent of India resides in the villages. Although many profess to the Hindu faith, superstitions and misconceptions prevail, and people simply perform rituals on certain dates. Because they have not been taught any philosophy, they are missing out on the wealth of wisdom available in the Vedic literature. Srila Prabhupada wrote many books that present the ancient Vedic knowledge in a way that a modern mind can accept. ISKCON has been working to present these teachings in the cities, but I saw no program that effectively taught people in the rural areas. Deep within me was a hankering to take the wonderful teachings of Lord Caitanya, as given by Srila Prabhupada, to my rural countrymen.”

One day someone gave Rupa Raghunatha a copy of the book Diary of a Traveling Preacher, by His Holiness Indradyumna Swami, an ISKCON sannyasi. For hours and hours Rupa Raghunatha immersed himself in reading and re-reading the wonderful adventures and amazing stories of Indradyumna Swami as he traveled the globe spreading Krishna consciousness in areas where no devotee had ever set foot before. The book gave Rupa Raghunatha the strategy he was looking for.

“I noticed a pattern of presenting Krishna consciousness that was highly successful,” he says. “The concept of holding a colorful festival with harinama (chanting), prasadam distribution, dramas, and cultural presentations cut across any manmade boundaries and universally attracted audiences of various backgrounds. Soon a similar concept began to evolve in my mind.”

Then came another break. After a three-year stint with the bus party, Rupa Raghunatha got the freedom to explore teaching in the villages. He was asked to head the village congregation development program around the temple’s newly acquired farm. Delighted, he readily accepted. Sanat Kumara Dasa, one of ISKCON Chowpatty’s four co-presidents and head of the new farm project, assisted him.

Teaching Krishna consciousness in villages has its own challenges. In a metropolis like Mumbai, one may use computers and offer multimedia presentations in air-conditioned halls to a sophisticated intellectual crowd. But in a village one may find half-naked dirty kids, shy women, simple hardworking peasants, and illiterate forest-dwellers. Illiteracy, superstition, and suspicion prevail. Roads are rarely maintained, and electricity is scarce.

Rupa Raghunatha rose to the challenge with his own improvised teaching aids.

“We began by traveling to villages on oxcarts, carrying a portable battery-charged sound system and buckets full of prasadam. We would do kirtana in the village and when a crowd gathered give a short speech and then distribute prasadam. We were visiting the same villages regularly, and young people came forward to ask questions. I would sit and talk with them, and gradually, in a few villages, they invited me for a regular talk. A core group developed.”

Another of his improvisations was a mobile display of Krishna conscious philosophy. He had seen a highly successful course on the basic teachings of Bhagavad-gita, such as karma, reincarnation, and yoga. The challenge was to replicate the slick multimedia presentation for the villagers. Rupa Raghunatha translated the words of the slides into Marathi, the language of Maharashtra, and then printed the slides on 3' x 3' plastic sheets, which he displayed on a tripod stand. Everything could be neatly packed in a shoulder bag. He traveled with this bag to his village programs and presented the six-session introductory course in an open area of the village.

After a core group developed, he decided to implement his dream of Hare Krishna festivals.

Festival Preparations

A group of village men meets the leaders of the village and gets permission to hold the festival. Five to ten devotees publicize the event and erect a pannal (large canopy). A few days before the festival, devotees take a palanquin with Gaura-Nitai deities through the village, accompanied by a chanting party. Villagers come out of their houses with arati plates and food to offer to the deities. Because people compete to render service to the Lord, it may take two to three hours to go down a single lane. So the devotees hold a collective arati at the end of the lane for all the residents. All this prepares the villagers for a bright festival day ahead.

The Day Of the Festival

Everyone has been eagerly awaiting the festival it’s a festival for the entire village. Villagers are in their best clothes. Men with bright turbans and women dressed in colorful saris join the harinama procession to the pannal. The dirt path leading to the pannal has been swept clean and sprayed with water to keep dust down. Women have drawn beautiful patterns and designs with dyed rice powder in front of their houses. At the entrance to the pannal is a welcome gate decorated with flags and auspicious banana trunks and leaves.

After an ecstatic kirtana and a welcome speech, the devotee children from the gurukula, a residential school on the ISKCON farm, perform an inspiring drama about the life of the seventeenth-century Maharashtran saint Tukarama. The crowd watches spellbound as the young children put on a sterling performance. The kids have spent hours watching a movie on the life of Saint Tukarama and have practiced for days for this show. The 45-minute drama describes vividly Tukarama’s faith in Lord Vitthala (Krishna), his turbulent marital life, his persecution by caste brahmanas, and how eventually he is able to lead the masses in chanting the holy names of the Lord.

In the final scene, Saint Tukarama goes back to the spiritual world. The devotees have built a wooden bird on which the boy playing the role of Tukarama Maharaja sits and ascends to the spiritual world. As the boy sings, Ami jato amcha gawa [“I am going back to my home”], the bird slowly ascends, pulled by ropes attached to a pulley above. People are so moved that many wipe tears from their eyes.

A local man who directs plays tells the audience, “That boy playing Tukarama acted so nicely that even if you bring any professional actor or film superstar, he cannot imitate the expression of that little boy!”

The play remains the talk of the village for many days to come.

Rupa Raghunatha then gives a short talk on the basic philosophy of Krishna consciousness. People have become so mesmerized by the drama, and their hearts so softened, that they openly accept the message. Then there is a final kirtana and prasadam for all.

The festival is followed by a fourday introductory Gita course with an exam. All the participants receive a completion certificate and are invited to a higher course, which later evolves into a regular teaching program.

Help comes from all quarters. Villagers donate rice, dahl, ghee, vegetables, and service. Varaha Rupa Dasa, a cook from Belgaum, volunteered to cook the entire feast for all the festivals. Congregation members donate money, stationery, and gifts for the participants. Other devotees come to participate in kirtana, book distribution, prasadam distribution, publicity, and the question-answer booth.

The Power of the Holy Name

The villagers remember the day as a never-before-seen spiritual festival.

“The kind of kirtana you played is still ringing in my ears,” a villager later tells the devotees. “It is so memorable, so jubilant to simply chant the holy names of the Lord and dance with no worry.”

For Rupa Raghunatha the path is clearly etched. With thousands of villages in Maharashtra, even if he spends one day in each village he will be occupied for many years. And then he can start again.

Sanat Kumara Dasa points to the success story of one village, where the inhabitants are mostly backward tribal people. With their own hands and using local material, they built a makeshift temple. It looks like other village huts, but it houses paintings of deities and is a meeting place for regular morning programs and chanting sessions.

“This is an expression of the change of heart that chanting can produce,” Sanat Kumara Dasa says.

“My desire is to turn villagers into friends of Lord Krishna,” Rupa Raghunatha explains, “to create awareness about Krishna consciousness, and to give out the holy name of Lord Krishna. We started this program with chanting the holy name. The holy name is the best advertisement, and it’s what keeps me inspired.”

Murari Gupta Dasa, a disciple of His Holiness Radhanatha Swami, has a Bachelor’s degree in medicine and surgery (M.B.B.S.) and is part of the production team of the Hindi and English editions of BTG in India. In compiling this article, he acknowledges the help of Uttama Sloka Dasa, Nagendra Dasa, Atula Krishna Dasa, and Devamrta Dasa.