With such an array of opinions as to why the Earth’s good health has waned, it is easy to see why society struggles to pinpoint the best approaches to environmental care. As a Hare Krishna devotee, and as an environmentalist since my childhood, I decided to investigate the underlying causes of such degradation from the perspective of the Vedas. When the opportunity to do a research Ph.D. through the University of Tasmania in Australia became available, I decided to employ the concept of the three modes of material nature to investigate the quality of consciousness of environmental scientists.

Understanding The Three Modes

The Bhagavad-gita and the Srimad- Bhagavatam both contain extensive descriptions of the three material modes, also referred to as the three qualities of material nature. Fundamentally, the three qualities compose a tripartite system of influence on all materially embodied beings, as well as on all aspects of the material creation. This includes the bodies and the mental and intellectual capacities of human beings, demigods, and all other living beings.

In the Bhagavad-gita (3.27) Lord Krishna says, prakrte˙ kriyamanani: one acts according to the particular modes of nature he has acquired. And in Message of Godhead Srila Prabhupada writes, “As long as the living entity remains conditioned by material nature, he has to act according to his particular mode of nature.” The influence of the three material qualities on the materially embodied individual is both psychological and biological. But while the three modes influence the body and mind of the embodied soul, they never change the soul itself.

Within the hierarchy of the three, sattva-guna, the mode of goodness, is superior to the modes of passion (raja-guna) and ignorance (tamoguna). The mode of ignorance is inferior to the mode of passion. This hierarchy is necessarily so, as the characteristics of the mode of goodness enable a person to peacefully focus on higher spiritual goals. In the mode of passion, one fervently endeavors to attain material prosperity to increase one’s sense gratification, thus to focus on spiritual goals is extremely difficult. In the mode of ignorance there is no interest in spiritual goals, what to speak of any favorable circumstances within which to cultivate such interest. As such, characteristics of the material mode of goodness endow one with a higher quality of consciousness than do the modes of passion and ignorance.

While the characteristics and symptoms of each mode are too numerous to list in this article, following is a concise listing. The mode of goodness: happiness, honesty, cleanliness, compassion, purity, humbleness, simplicity, greater knowledge, interest in spiritual life, and control of the mind and senses.

The mode of passion: lust, misery, false pride, great attachment, sense gratification, knowledge based on duality, the seeking of honor and recognition, unsteady perplexity of the mind, and intense endeavor to advance materially.

The mode of ignorance: nescience, madness, depression, laziness, violence, delusion, hypocrisy, intolerant anger, false expectations, acting whimsically, and a lack of interest in spiritual life.

Results of Acts in the Modes

Lord Krishna explains in both the Bhagavad-gita and the Srimad- Bhagavatam that activities carried out in the mode of passion are destined to end in misery, anxiety, and struggle, while activities carried out in the mode of ignorance are destined to end in violence, foolishness, and helplessness. Activities carried out in the mode of goodness, on the other hand, are destined to end in peace, prosperity, satisfaction, and real knowledge.

The results of such sattvic activity enable one not only to progress toward higher spiritual goals, but also to attain immediate material goals with less difficulty. From the mode of goodness, therefore, environmentalists can most easily achieve the goals of global environmental management, such as minimizing pollution, achieving environmental sustainability, improving the quality of edible crops, and preserving all species of life. By adopting characteristics from the mode of goodness and working within their boundaries, environmentalists can expect a higher rate of success in attaining environmental management goals than those who maintain characteristics from the modes of passion and ignorance. The Srimad- Bhagavatam confirms this when it states that the Earth, known as Mother Bhumi in the Vedas, responds unfavorably to acts performed within the lower modes of passion and ignorance, but favorably to acts performed within the mode of goodness.

Although the three material qualities are present everywhere within the material universes, they manifest themselves in different ways and in different proportions to each other according to different mundane circumstances. For example, in a liquor outlet or a brothel the mode of ignorance is the most prevalent of the three, as its characteristics of irreligion, degradation, intoxication, and uncleanliness are prominent. In the business world the mode of passion is the most prominent, with its focus on material gain through hard labor. Characteristics such as intense endeavor, sense gratification, and hard work to acquire prestige and fortune are typical in such settings. In religious and ethically-focused organizations the mode of goodness is the most prevalent due to the abundance of the characteristics of virtue, piety, purity, greater knowledge, and faith directed toward spiritual life. Therefore, according to the prevalence of different characteristics from the different modes within each mundane setting, one or two modes will typically predominate over the other one or two.

Just as the balance of characteristics from each of the three material modes varies within the above-given settings, so also do they vary within different environmental management settings. While students of Bhagavad-gita and Srimad-Bhagavatam can easily detect some such variety, much remains obscure and hidden to the naked eye. The tamasic characteristics of violence, irreligion, and detestability are evident in animal slaughter. The rajasic characteristics of greed, dissatisfaction, and great attachment are evident in management practices involving excessive proprietorship claims over the Earth. And the sattvic characteristics of mercy, piety, and spiritual insight are evident in animal protection, the cultivation of vegetarian foodstuffs, and decision-making based on spiritual aspects of the natural environment.

An essential lesson from the Vedas is that the three material qualities manifest themselves within a particular material setting according to the consciousness of those taking part in it. As such, the material modes reveal themselves within environmental management practices according to the consciousness of environmental scientists, managers, and policy-makers, as well as other persons instrumental in environmental management programs.

Among such contributors, environmental scientists play a key role. Not only are they entrusted with the onerous task of delivering factual information on the workings of material nature to the rest of the world, but they are also often called upon to advise managers on optimum strategies. As such they often contribute toward both management strategies and policy formulation.

The Study Sample

For my study sample I chose the Australian Antarctic scientific community, made up of several hundred environmental scientists. Their research fields include geophysics, biology, astronomy, geology, human impacts, glaciology, meteorology, paleontology, oceanography, and space and atmospheric sciences. Scientists maintain that the Antarctic continent acts as the engine room for the entire Earth’s weather patterns. It thereby follows that both the natural phenomena within the region and the science carried out there have global significance.

My official research objective was “To investigate if there exists a need for environmental scientists to raise the qualitative level of their consciousness, for the purpose of enhancing outcomes of environmental management activities.” I defined “consciousness” as an individual living being’s awareness. It followed that “quality of consciousness” would be determined by “The degree to which an individual’s conscious awareness is afflicted by material desires and material characteristics. The greater the affliction, the poorer the quality.”

This definition proposed that materialism is the root cause of poor quality of consciousness in general. I stipulated at the outset of my thesis that if my investigations found that scientists predominate within either the mode of passion or ignorance, then they would be considered to be suffering from a poor quality of consciousness.

I organized the characteristics of each mode according to their anticipated relevance to environmental science. I asserted that by collecting data on such things as scientists’ research activities, workplace relations, and professional motivations, and by analyzing these data against the characteristics of each mode, I could gain an accurate picture of how environmental scientists are situated within the triguna. I also asserted that by identifying which material mode and which specific characteristics were the most prevalent within the Australian Antarctic scientific community, I could build a fairly accurate profile of the current quality of consciousness of environmental scientists.

Would the data reveal, for example, that scientists predominate within the mode of goodness, with only a weak representation within the other two modes? Or would it reveal that they affiliate strongly with two modes, such as goodness and passion, with the mode of ignorance being only minimally supported? Or would I see some other mixture of the modes.

To answer these questions, I designed models for data collection and processing. The main data-collection item was an inventory based on the three material modes, in which each of sixty statements represented either the mode of goodness, passion, or ignorance. For example, the statement “It is very important to me to be thoroughly honest in all of my work as a scientist” represented the mode of goodness, as honesty is a sattvic characteristic. The statement “I am proud to be an Antarctic scientist” represented the rajasic characteristic false pride. And the statement “I usually procrastinate in my daily schedule” represented the tamasic characteristic procrastination.

I asked scientists to respond to each statement by marking one of five Likert-scale options on their papers, ranging from “I strongly agree” to “I strongly disagree.” Other data-collection items included an examination of Australian Antarctic science publications and interviews with scientists.

Looking at the Results

The overall results revealed that Australian Antarctic scientists predominate within the mode of passion. Prominent rajasic characteristics included sense gratification, intense endeavor, seeking honor, and creating theories and doctrines through logic and speculation.

Particularly prominent was sense gratification, in the form of scientists’ seeking mental stimulation from their work. Srila Prabhupada describes the mind as the sixth and chief material sense. Scientists’ desires to satisfy their minds through interesting, challenging, or pleasurable scientific activities thereby constitute one type of sense gratification, regardless of how sophisticated such activities may be.

The mode of goodness received the second highest support from scientists, with the sattvic characteristics of mercy, honesty, cleanliness, and careful study of the past and future being the most prevalent.

The mode of ignorance received the least support. Most prevalent were the tamasic characteristics of speaking (publicizing) without without scriptural authority, acquiring knowledge without any higher purpose, and being uninterested in and unconcerned about spiritual matters.

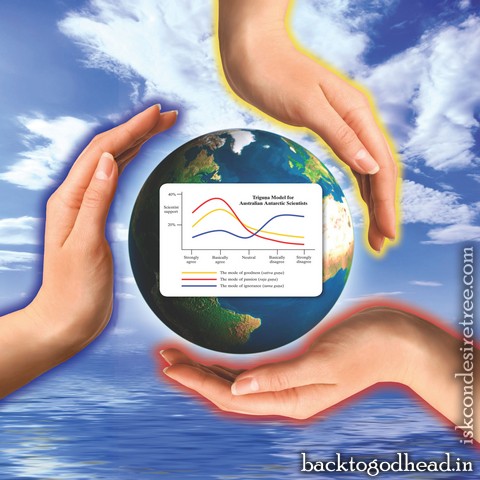

The graph in the illustration on the opening spread depicts scientists’ standing within the triguna. The most common quality of consciousness among scientists was raja-guna, with which 38% “basically agreed.”

Although the results revealed that Australian Antarctic scientists do not maintain many tamasic characteristics, responses to question seven predominated within that mode: “Do you have any thoughts on the process of peer review as a means by which to ensure rigor in Antarctic scientific research?” The scientists’ responses to this question predominated within the mode of ignorance because they persist in relying on the peer-review system even though they are aware that it is full of faults. A typical response: “It’s fraught with all sorts of problems, but I think it’s the best system we can use at the moment.” That scientists are aware of the defective nature of the peer-review system but still use it to deliver scientific knowledge to other scientists, academics, and the public suggest tamasic characteristics such as hypocrisy, irresponsible work, indulgence in false hopes, speaking without scriptural authority, and acting in illusion, without regard for scriptural injunctions or concern for future bondage for oneself or for violence or distress caused to others.

In Bhagavad-gita As It Is (14.7) Prabhupada states that “modern civilization is considered to be advanced in the standard of the mode of passion.” As symptoms of one whose consciousness is predominated by the mode of passion include unsteady perplexity of the mind and distortion of the intelligence because of too much activity, it is easy to see how science carried out within this mode harms environmental management strategies. Afflicted with such symptoms, scientists can hardly be expected to conduct research that will help restore and preserve the Earth’s good health. Conversely, if scientists were conditioned primarily by the mode of goodness, their symptoms would include sobriety and the ability to see things as they really are. The sattvic characteristics of speaking words that are truthful, pleasing, beneficial, and not agitating to others, and regularly reciting Vedic literature, may thereby manifest themselves within environmental science policy and publications. If such changes could be instigated, management programs might also come to address spiritual needs, not just material ones. Mother Bhumi, a pure devotee of Lord Krishna, would certainly be pleased by such changes appearing within current environmental management practices.

Padma Devi Dasi is a disciple of His Holiness Prabhavisnu Swami. After completing her university studies in Australia, she moved to Vrndavana, where she hopes to stay and write and publish Krishna conscious books.