Bombay's most popular cultural center inspires a renaissance in India's arts and sciences.

Constantly blending old with new, Bombay, the world's seventh largest city and India's headquarters for business and industry, is a place of contrasts: high-rise luxury apartment buildings dwarfing ramshackle ghettos; women laborers balancing hundred-pound stacks of bricks gingerly on their heads; marble temples surrounded by rickety billboards announcing the latest romance film; traffic jams of cars, trucks, buffalos, and elephants; a nuclear reactor encircled by bamboo scaffolding that sways precariously in the hot, dusty breeze.

There is another, unexpected contrast in Bombay. Leaving the heat and, noise of center city on a Sunday afternoon, as many as 30,000 pilgrims journey forty-five minutes by train or bus to prestigious Juhu Beach, where breezes from the Arabian Sea offer welcome relief, and where the skyline of concrete and glass gives way to palm trees and the multidomed outline of the Radha-Rasavihari temple, the central structure of Hare Krsna Land.

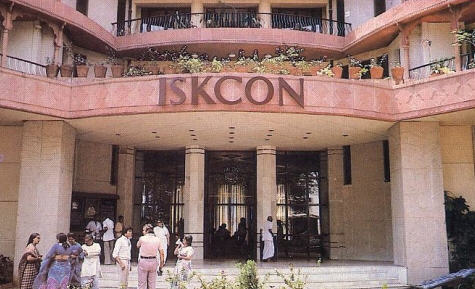

Built by the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (1SKCON) as a place of pilgrimage and culture. Hare Krsna Land receives two to three thousand guests daily, ten times that many on Sundays, and as many as 100,000 for its major festivals. Visitors include Bombay residents attracted to the opulent worship of Lord Krsna and discourses on Bhagavad-gita, tourists from abroad who come for the four-star hotel service offered at the Juhu center, and local children who assemble out back for games organized by devotee teachers. In the evening, people assemble in the auditorium for the science seminar sponsored by the Bhaktivedanta Institute, or the classical drama, dance, or musical performance organized by ISKCON's Center for the Devotional Arts (Bhakti Kala Kshetra). Other guests have dinner at Govinda's, Bombay's most popular vegetarian restaurant.

The 1SKCON cultural complex resides on four acres of verdant land two minutes from the beach. Also on the property is a two-story book depot. Here devotees load buses and bullock carts for traveling from village to village, distributing the message of Lord Krsna in books and magazines they have translated into Hindi, Gujarati, Telugu, Sindhi, and other local languages. The publishing is supervised by His Holiness Gopala-Krsna Goswami, the director for ISKCON's affairs in western India.

Toward the rear of Hare Krsna Land stand the foundations of the Gurukula, a school for children, financed in part by G.D. Birla, octogenarian head of India's leading industrial family. "For doing this work," he told Giriraja Swami, "may God bless you."

Giriraja Swami, an American-born sannyasi (devotee in the renounced order of spiritual life), heads the Juhu project. Under his direction it has grown to include an active membership of 8,000 (more than Bombay's popular Lions or Rotary clubs), an advisory committee of industrialists and influential civic leaders, and a congregation numbering in the hundreds of thousands. Intact, in this city of six million people it is hard to find anyone who has not at least once visited the famous Hare Krsna Land at Juhu.

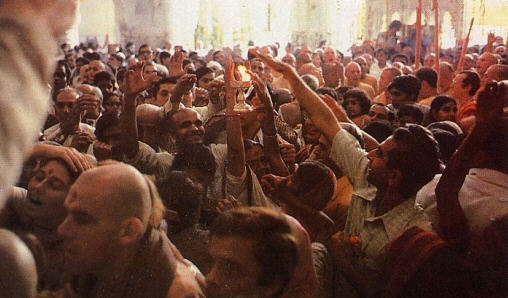

Morning Bhagavatam Class at ISKCON Juhu

Giriraja Swami explains, "Srila Prabhupada, ISKCON's founder and spiritual guide, envisioned such a project twenty years ago, when he was preparing to bring the teachings of Lord Krsna to the West. He knew that many Westerners coming to India formed bad impressions, that India by Western standards appeared a poverty-stricken nation. He also knew that few Westerners know where or how to look to discover India's spiritual wealth. So after establishing Krsna consciousness in America and Europe, he returned with his disciples and built Hare Krsna Land."

For months after the devotees arrived, they held public festivals that drew as many as 40,000 people at a time and raised millions of rupees for construction. More than half the funds needed to build Hare Krsna Land came from abroad, from devotees and sympathizers who shared Srila Prabhupada's vision of a holy place in Bombay. When the center opened, in 1978, twenty thousand visitors attended, along with media from four continents and a host of dignitaries. Indian Health Minister Raj Narain remarked, "It is amazing to me that you Westerners have taken to the Indian culture just now when we are losing it."

Many Bombay residents believe that beauty, dignity, and divinity were sacrificed when India's political leaders chose the path of Westernization, and that Hare Krsna Land safeguards important elements of that waning spiritual heritage: classical arts and architecture, consummate vegetarian cuisine, temple worship, and scriptural instruction to the highest Vaisnava standard.

Sadajiwatlal Chandulal, Bombay businessman and former president of the Hindu Vishwa Parishad (an international religious organization), knew Srila Prabhupada before his departure for the West. He says, "There was little appreciation in India for his efforts to revive Krsna consciousness, and therefore he went to the West to launch his movement. After independence in 1947, rather than return to her own spiritual traditions, India diverted herself to materialism and the pursuit of personal wealth. It was a gloomy picture, but upon his return Prabhupada injected new life with his vigorous preaching and projects like Juhu."

Since the 1940s, scholarly misinterpretations of Bhagavad-gita have attempted to deny Krsna's divinity and minimize the value of devotional culture. Slogans like "Factories are our temples" became harbingers of a bright new future, while religious customs and beliefs fell to the status of antiquated and empty rites.

"By going abroad and proving the universality of Krsna consciousness," Sadajiwatlal says, "Prabhupada permitted people to feel pride in their own spiritual convictions. He showed that true devotional life was not the cause of India's social problems but rather her only hope."

Part of India's Westernization included importing foreign modes of dress, conduct, and entertainment. Today India produces more commercial songs and films than any other country in the world, much to the regret of even some artists who have made fortunes for commercial cinema in India.

Hema Malini is to Indian cinema what curry is to rice: an all-pervasive influence. Her beauty and stardom are known across the subcontinent. But of her seventy-five films in the past thirteen years, only one Meera, the story of India's greatest devotional poetess stressed a spiritual message.

"Nobody went to see it," she acknowledges with a sigh. "I would be happy to play more devotional parts, but the public has lost all interest. One of the few consolations I have is the ISKCON center at Juhu. The devotees and the spiritual programs they sponsor have increased devotion in the arts. Not just any temple can do that. I think it is because ISKCON always stresses Krsna in its programs, whereas other places may encourage worship but without any personal, devotional quality to the gestures."

Hema Malini demonstrated her appreciation by becoming a Life Member of the Society and offering a benefit classical dance performance at the ISKCON auditorium last year.

Every evening crowds gather at the auditorium for programs organized by ISKCON's Center for the Devotional Arts. Some evenings the devotees perform plays in Hindi or Bengali from the Vedic scriptures, but usually guests are treated to music or dance by one of India's top artists singers such as M.S. Subhalaksmi and Hari Om Sharan and dancers like Vyjayanthimala Bali and the Jhaveri Sisters.

"Dance and music have always been integral to India's devotional life," explains Nayana Jhaveri, head of the renowned family of Manipuri dancers. "Previously, saintly kings were patronizing these things, and through public performances even common people learned about Krsna's pastimes and our eternal relationship with Him. Spirituality was the essence of art. Now western education has changed that, and with the loss of devotion has come aggressivity and crassness in the arts.

The Jhaveri Sisters have given benefit performances at ISKCON temples in Mayapur, Vrndavana, and Bombay. Recently they also danced at the ISKCON Ratha-yatra festivals in Italy and France.

"The best opportunity for artists to make devotional offerings to Lord Krsna," says Nayana Jahveri, "is at ISKCON festivals."

ISKCON Juhu Center

Devotees sponsor spiritual festivals monthly, not only in India's big cities but also in the small villages that are home for seventy percent of the population. Sometimes 10,000 villagers join the devotees in chanting Hare Krsna. Distribution of prasadam(sanctified vegetarian foods) plays an important part in these gatherings, as do the discourses given by devotees in native languages. A European or American devotee speaking Lord Krsna's message in a local dialect triggers dozens of "aachas," India's universal expression of surprise.

"It's not just the novelty of Western devotees that impresses people," says Brijrattan Mohatta, director of several engineering and chemical-manufacturing companies in Bombay, "what attracts people is also the purity of their message. Indians have grown accustomed to self-appointed 'Gods' who promise moksa [liberation] in exchange for money. But Prabhupada taught his disciples to speak according to sastra [scripture] and to live their lives by strict brahminical standards. Today ISKCON is one of India's best known and best supported institutions for that one reason alone."

Outside India, Krsna temples rely on the proceeds from literature distribution and devotee-run businesses for their maintenance. In it's country of origin, however, ISKCON rests on solid popular support that crosses all barriers of caste and creed a phenomenon that sets it apart from the numerous temples of India where non-Hindus are denied participation. At Hare Krsna Land, for example, the manager is from a Hindu family, the bookkeeper is a Jain, one of the project coordinators is Muslim, another Christian, the secretary comes from a Jewish family, and the initiating guru is the son of a Baptist minister.

"The rest of India reflects whatever is done here," says R.K. Maheshwari, a lawyer and initiated ISKCON devotee. "Inject something good into Bombay, and the whole country benefits. So Krsna consciousness has been a unifying force in this country, not by making converts but by demonstrating how people, whatever their caste or background, can be happy by directing their energies to the service of God."