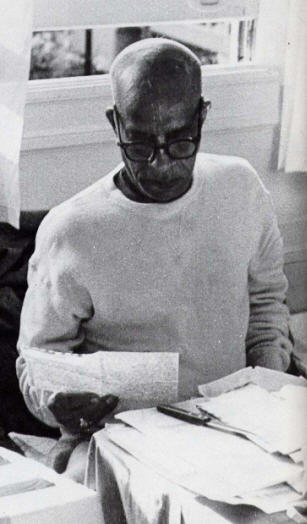

New York City, Winter 1965-1966

The building at 100 West Seventy-second Street was rented as office and studio space, and none of the tenants, who included the members of the Misra Yoga Society, stayed there overnight. For Srila Prabhupada, however, his room on the fifth floor was his sole residence, and he had to use it even for sleeping. While he sat alone at 6:00 P.M on November 9, the lights in his room suddenly went out. In India power failures occurred commonly, so Srila Prabhupada; though surprised to find the same thing in America, remained undisturbed and began chanting the Hare Krsna mantra on his beads. This was his experience of the first moments of the New York City blackout of 1965, a massive power failure that suddenly left the entire city without electricity. The blackout trapped 800,000 people in the city's subways and affected more than thirty million people in nine states and three Canadian provinces.

Dr. Misra sent a man from his apartment with a candle and some fruit: The man found Srila Prabhupada sitting in darkness, reciting the holy names of Krsna. When informed of the breakdown (it lasted until 7:00 A.M. the next morning), Srila Prabhupada responded by remaining in his place and chanting. For the cause of Krsna consciousness he was prepared to work in the city as actively as any karmi (materialistic worker), but if all facilities were taken away, he would be ready as he was in any calamity to see this as Krsna's will and turn his full attention to the utterance of the holy names.

Srila Prabhupada had to wait more than two weeks before he received a reply to his letter of November 8 to Tirtha Maharaja, his Godbrother in Calcutta. His hopes and plans for staying in America, he had said, depended on a favorable reply but could he expect one? We have already described to some extent the history of the Gaudiya Math, the spiritual mission organized in India by Srila Prabhupada's spiritual master, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura. It was well known to everyone involved that the Godbrothers, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta's disciples, were not working cooperatively. Each leader was interested in maintaining his own building, but not in a unified effort to spread the teachings of Lord Caitanya. How, then, could Srila Prabhupada expect them to share his vision or establishing a branch in New York City? Probably they would see it as his separate attempt, but despite the unlikely: odds, he had appealed to their missionary spirit and to the desires of their spiritual master, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura. For they all knew well that their Guru Maharaja, their' spiritual master, had wanted Krsna consciousness spread in the West.

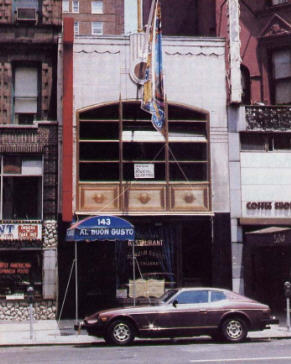

While waiting for a reply from the Gaudiya Math, Srila Prabhupada found a building that he considered suitable for the first Krsna temple in America. It was located on the same block as Dr. Misra's studio. Having inquired from the broker, Louis Baum, who represented Phillips, Wood, Dolson, Inc., he received a description of the desired property, at 143 West Seventy-second Street. The building measured only eighteen and one-half feet across and was one hundred feet deep. It contained a basement, above which was a store of the same size, and a mezzanine. The asking price was $100,000, with a $20,000 cash down payment. So Srila Prabhupada wrote to Tirtha Maharaja again, presenting these figures. He remarked that this building was twice as big as their Research Institute in Calcutta. The basement could be used as a cooking and dining facility, the store as a lecture hall, and the mezzanine for installing Deities of Krsna and for personal apartments. He said that if they could invest their money in this property and start a branch, they could call it the Sri Caitanya Math or New York Gaudiya Math.

Srila Prabhupada offered evidence that his preaching was being well received. On one of his walks he had visited the Indian Consulate on Sixty-fourth Street and met Lakhanlal Mehrotra, a Consulate officer. Through him Srila Prabhupada had made contact with the Tagore Society, with which he arranged a lecture. In his letter to Tirtha Maharaja, he included a copy of the Society's invitation:

The Tagore Society of New York, Inc.

CORDIALLY INVITES YOU

to a lecture "God Consciousness"

by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami.

Date: Sunday, November 28th, 1965.

Time: Lecture, 3:30 P.M.

Tea, 4:30 P.M. Place: New India House,

3 East 64th Street.

A widely respected scholar and religious

leader in India, Swami Bhaktivedanta

is briefly visiting New York. He has

been engaged in the monumental endeavor

of translating the sixty-volume

Srimad-Bhagavatam from Sanskrit

into English.

A doctor Haridas Choudry was also preparing to arrange lectures for him in San Francisco and Los Angeles. "But in my opinion," Srila Prabhupada said, "such casual lectures may be a good personal advertisement, but factually they do not make any permanent effects. But if there is a center of activity for attracting people as you are doing in Research Institute, the people can be trained up by regular association and hearing the transcendental sounds of Srimad-Bhagavatam."

When Srila Prabhupada finally received Tirtha Maharaja's reply, he found it unfavorable. Tirtha Maharaja, his Godbrother, did not argue against Srila Prabhupada's attempting something in New York, but he politely said that funds from the Gaudiya Math could not be gathered and turned over for such a venture. On November 23 Srila Prabhupada wrote him back, "It is not very encouraging. Still, I am not a man to be disappointed."

Srila Prabhupada was convinced that if he could start a place where people could come and associate with a pure devotee, the genuine God conscious culture of India could begin in America. But because his plans depended on obtaining an expensive building in Manhattan, his goal seemed unreachable. Nonetheless, while in correspondence with Tirtha Maharaja;" Srila Prabhupada also persistently wrote to known Vaisnavas (devotees of Krsna) in India for help in starting a Krsna temple in Manhattan. He thought, Why should they nor help? After all, he was addressing devotees of Krsna. Shouldn't the devotees of Krsna come forward to establish the first Krsna temple in America?

As a Vaisnava guru in the line of disciplic succession from Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Maharaja and Lord Caitanya, Srila Prabhupada was certainly authorized to spread the message of Krsna. As for the location, New York City was perhaps the most cosmopolitan center in the world and the building he had found there, although well located, was not very expensive for that area. Moreover, there was a great need for a Krsna temple, to offset the propaganda of the Indian Mayavadis, or impersonalists

The Krsna devotees to whom Srila Prabhupada was writing understood Lord Krsna to be worshipable for the whole world, and so it should have been very desirable for them to see Krsna worshiped in a place like New York. In Bhagavad-gita Lord Krsna Himself had said, "Give up all activities and surrender to Me."? Lord Caitanya had also stated that the name of Krsna should be heard in every town and village. So if the Indian Vaisnavas were Krsna's devotees why should they not help? What was a person's money for but to glorify Krsna? If one was a Krsna devotee and did not want to glorify the Lord, what kind of devotee was he?

One obvious answer is that although the people Srila Prabhupada wrote to were devotees of Krsna, they were devotees who were not prepared to surrender to such a full extent. Although as devotees of Krsna they were obliged to surrender everything to Krsna, Srila Prabhupada found them unable. Perhaps he should not have seriously counted on them to do so. But as a preacher in the field, he had no business deciding beforehand that people could not surrender. Following the order of his spiritual master, he had to approach everyone and ask everyone for help.

Srila Prabhupada still cherished hopes that Sumati Morarjee would help in a large way. She had initially helped him in publishing the Bhagavatam, and she had sent him to America. As he was later fond of recalling, she had also written him, while he was in Butler, that he should not return to India until he had fulfilled his mission. Srila Prabhupada had received that note in Butler, and shortly after his arrival in New York he had replied from Dr. Misra's studio. Several weeks later, not having received any further response, Srila Prabhupada wrote her again, this time with a specific request. He addressed her as "Madam Sumati Morarjee Baisahib."

"So far as I have studied," he wrote, "the American people are very much eager to learn about the Indian way of spiritual realization, and there are so many so-called yoga asramas in America. Unfortunately they are not very much adored by the government, and it is learned that such yoga asramas have exploited the innocent people, as has been the case in India. The only hope is that they [the American people] are spiritually inclined, and immense good can be done to them if the message ofSrimad-Bhagavatam is preached here."

Srila Prabhupada noted that Americans were also giving a good reception to Indian art and music. A Madrasi dancer named Balasaraswati had held a performance in New York, and Srila Prabhupada had attended. "Just to see the mode of reception, I went to see the dance with my friend, although for the last forty years I have never attended such a dance ceremony. The dancer was successful in her demonstration. The music was an Indian classical tune, mostly in Sanskrit language, and the American public appreciated them. So I am encouraged to see the favorable circumstances about my future preaching work." Srila Prabhupada suggested that the Bhagavatam could also be preached through music and dance, although he had no means to introduce this. The Christian missions, backed by huge resources, were preaching all over the world, so why couldn't the devotees of Krsna combine to start a mission to preach the Bhagavatam all over the world? He also noted that Christian missionaries could not be effective in checking the spread of communism, whereas the Bhagavatam movement could be, because of its philosophical, scientific approach.

Srila Prabhupada appealed to Sumati Morarjee to consult "your beloved Lord Bala Krsna" and try to help. (Bala Krsna means "child Krsna." Srila Prabhupada knew that Sumati Morarjee was a Gujarati and a follower of the Vallabha sampradaya, which worships Bala Krsna.) But again Srila Prabhupada received no reply, so he wrote to her again some weeks later. Srila Prabhupada expressed his idea for how to organize preaching: "They [the American people] should have association of bona fide devotees of the Lord, they should join the kirtana [chanting of the Lord's names], they should hear the teachings of Srimad-Bhagavatam, they should have intimate touch with the temple or place of the Lord, and they should be given ample chance to worship the Lord in the temple. Under the guidance of a bona fide devotee they can be given such a facility, and the way of this Srimad-Bhagavatam is open for everyone…. I think therefore that a temple of Bala Krsna in New York may immediately be started for this purpose, and as a devotee of Bala Krsna you should execute this great and noble work."

Srila Prabhupada informed Sumati Morarjee that as a sannyasi he had no ambition to become the proprietor of a house in America, but for preaching the house was absolutely required. He gave her the details of the building and reminded her of the importance of distributing prasada, food offered to Krsna. She well knew that such spiritualized food would purify the consciousness of all who tasted it and would help them to come closer to Krsna.

"The house is practically three stories. Ground floor, basement, and two stories up, with all the suitable arrangements for gas, heat, etc. The ground floor may be utilized for preparation of prasada of Bala Krsna, because the preaching center will not be for dry speculation but for actual gain and delicious prasada. I have already tested how the people here like the vegetable prasada prepared by me. They will forget meat-eating and pay for the expenses. The American people are not poor men like the Indians, and if they appreciate a thing they are prepared to spend any amount on such hobby. They are being exploited simply by jugglery of words and bodily gymnastics, and still they are spending for that. But when they will have the actual commodity and feel pleasure by eating very delicious prasada of Bala Krsna, I am sure a unique thing will be introduced in America."

At the time he wrote this letter, Srila Prabhupada, according to the terms of his visa, had a week left in America. "My term to stay in America," he wrote, "will be finished by the seventeenth of November, 1965. But I am believing in your foretelling 'You should stay there until you fully recover your health and return after you have completed your mission.' "

While his letter-writing campaign went on, interspersed with long periods of waiting (sometimes he sent two or three letters without response), Srila Prabhupada still had to survive daily in New York. America seemed so opulent, yet many things were difficult to tolerate. The sirens and bells from fire engines and police cars seemed like they would crack his heart. At night he would sometimes hear a person being attacked and crying for help. From his first days in the city, he had noted that the smell of dog stool was everywhere. Although it was such a rich city, he could rarely find a mango to purchase, and if he did, it was very expensive and usually had no taste. From his room he would sometimes hear the horns of oceanliners come, and he would dream that someday he would sail around the world with the sankirtana party, preaching in all the major cities. November passed and December came, and somehow he stayed on. During early December the newspapers reported that New York City's hospitals were admitting increasing numbers of young people disoriented by LSD, and that protest was mounting against America's participation in the Vietnam war.

Srila Prabhupada's original plan was to stay in America for two months at most. but he had now set that aside. He wanted to return to India, but even more he wanted to carry out his spiritual master's order. Just to assuage his yearning tc return, he would go down to the Battery in Manhattan and inquire from a shipping agent, "When is the next ship going to India?" Eventually the agent became his friend and would say to him, "You are always asking when the ship is returning to India, but, Svamiji, when are you going to return?" Sometimes Srila Prabhupada would fix a date and a particular ship on which he planned tc leave, but when the time came he would not go.

The weather went below freezing, colder than he had ever known in India, He had to walk daily toward the Hudson River, against the west wind, which takes away one's breath and makes one's eyes water, even on an ordinary winter day. On a stormy day, the sudden gusts of wind could even knock a man down. Sometimes a cold rain would turn the streets slick with ice. The cold would become especially biting as Srila Prabhupada approached the open area of Westside Drive, where the winds sometimes spun tornadolike, catching brown leaves in a whirling current.

Dr. Misra gave him a coat, but Srila Prabhupada never gave up wearing his dhoti, although it became difficult to walk against the gusts. Swami Nikhilananda of the Ramakrishna Mission had advised Srila Prabhupada that if he wanted to remain in the West, he should abandon strict adherence to the Indian habits of simple dress and pure vegetarian diet. Meat and liquor and pants and a coat were almost a necessity in this climate, he had said. Even before Srila Prabhupada had left India, one of his Godbrothers had demonstrated to him how he should eat in the West with a knife and fork. Srila Prabhupada never considered taking on any of these Western ways. His advisors counseled him not to remain an alien, but to get into the spirit of American life, even if this meant breaking vows one held in India. Almost all Indian immigrants compromised their old ways. But Srila Prabhupada's ideas were different, and he could not be budged. Others may have to compromise, he thought, because they have come to beg technological knowledge from the West. "But I am not a beggar," he said, "I am a giver." His intention was not to learn the ways of the mlecchas (uncultured Westerners), but to teach the Westerners how to do things according to the Vedic culture. Srila Prabhupada, in his solitary wanderings, became known to a number of local city people. One was Mr. Ruben, a Turkish Jew who in the winter of 1965 and 1966 was working as a New York City subway conductor. Mr. Ruben first saw Srila Prabhupada sitting on a park bench, and being an outgoing person and something of a world traveler, he sat and talked with the Indian holy man.

He seemed to know [Mr. Ruben relates] that he would have temples filled up with devotees. He would look out and say, "I am not a poor man. I am rich. There are temples and books. They are existing, they are there, but the time is separating us from them. " He always mentioned "we" and spoke about the one who sent him, his spiritual master. He didn't know people at that time, but he said, "I am never alone. " He always looked like a lonely man to me. That's what made me think of him like a holy man, Elijah, who always went out alone. I don't believe he had any followers.

When the weather was not rainy or dry, Srila Prabhupada would catch the bus every day to Grand Central Station and walk down Madison Avenue or Forty-second Street, sometimes visiting :he library. He would also walk over to :he New India House on East Sixty-fourth Street or walk past the United Nations Building. Riding the bus down Fifth Avenue, he would look at the big buildings and imagine that some day .hey could be used in Krsna consciousness. Materialists had erected such enormous structures and yet had made no provisions for spiritual life, and therefore, in spite of all the great achievements of technology, people ended up feeling empty and useless. They had built these big buildings, but their children were going to LSD. As he traveled downtown, various buildings would attract his mind as potential homes for a temple: a building on Twenty-third Street, a building on Fourteenth Street with a dome.

The weather continued to get colder, but there was no snow in December. On Seventy-second Street, the Retailer's Association erected tall red poles with great tinsel Christmas trees on top. From the top of each pole sprouted a long tinsel garland, which extended from either side of the street to meet its counterpart in the middle, in a red tinsel star surrounded by multicolored lights. Some of the shops on Columbus Avenue sold Christmas trees, and the continental restaurants were bright with holiday lighting.

Though Srila Prabhupada did no Christmas shopping, he stopped at a number of book stores, where he attempted to sell sets of Srimad-Bhagavatam. He visited Samuel Weiser's book store, the Doubleday's, and the Paragon Book Gallery on Thirty-eighth Street.

Mrs. Ferber, the wife of the Paragon Gallery's proprietor, remembers Srila Prabhupada as "a pleasant and extremely polite small gentleman." The first time he called, she says, he wasn't able to interest them in his books, but when he tried again she and her husband took them. Srila Prabhupada used to stop by the Paragon about once a week. And since the books were selling regularly, he was usually able to collect small amounts of money from sales. He left a number of books with them, and whenever he needed a copy to sell personally, he would come in and pick it up at the Paragon. Sometimes he would phone and ask how they were selling.

Mrs. Ferber says that every time Srila Prabhupada came, he would ask for a glass of water. "If an ordinary customer had made such a request, I would ordinarily have said, 'There is the water cooler.' But because he was an old man, I couldn't tell him that, of course. He was very polite always, very modest, and a good scholar. So whenever he would ask, I would fetch him a cup of water personally." One time Srila Prabhupada conversed with Mrs. Ferber about Indian cuisine, and she mentioned she especially liked samosas (spicy, vegetable-filled savories). The next time he visited he brought a plate of samosas and gave them to her. She enjoyed them and remembers the occasion well.