The recipe for ruining relationships

A heart-rending Ramayana story offers invaluable lessons for avoiding alienation and promoting reconciliation

One of the most poignant subplots in the Ramayana is the fratricidal confrontation between the two monkey brothers, Vali and Sugriva. In the Mahabharata, fraternal animosity between the virtuous Pandavas and the evil Kauravas continues till the death of the Kauravas. In contrast, the Ramayana features a deathbed reconciliation between the simian siblings that is as emotionally riveting as it is ethically illuminating. In the bhakti tradition, the pastimes of the Lord and his devotees are primarily celebrated and cherished for their spiritual potency – hearing them evokes divine emotions within us, purifies our heart of ungodly attachments and redirects our attraction from the world to him. Additionally, the tradition sometimes see in those pastimes ethical guidelines that can help us to lead more harmonious lives during our stay in this world as we purify ourselves by practicing bhakti. Thus, for example, in the Ramayana, Lakshmana and Bharata are seen as inspirations for fraternal selflessness; and Sita is seen as an inspiration for wifely sacrifice. In this article, I will focus on the ethical import of the denouement of the Vali-Sugriva relationship.

The Awesome Twosome

The story of these two brothers unfolded in Kiskindha, the kingdom of the Vanaras in southern India. The Vanaras were a race of celestial monkeys possessed of formidable strength and intelligence, with some monkey-leaders having more sapient attributes than simian. Kiskindha’s location was geopolitically significant, being situated strategically between the kingdom of humans in the north and the kingdom of the demons in the south. Throughout their childhood and youth, Vali and Sugriva were inseparable. Like the Pandavas, they both had dual sires: one earthly, one heavenly. Their earthly father was Aksaraja, the king of the Vanaras. And their heavenly fathers were Indra and Surya respectively, two of the most powerful gods. Just as Indra was higher in the cosmic hierarchy than Sürya, Vali, being older and stronger, was higher than Sugriva. Just as Indra was given to bouts of arrogance and impetuosity, so was Vali. Just as the two gods worked harmoniously in the cosmic administration, their two sons worked harmoniously in the administration of the monkey kingdom. When Aksaraja retired, in accordance to the tradition of primogeniture, Vali ascended the throne of Kiskindha. And Sugriva became his faithful and resourceful assistant.

Once a fearsome demon Mayavi came to Kiskindha and challenged Vali for a fight. The Vanara monarch sprang up from his throne and came out, followed closely by Sugriva. If there was to be a fight, Vali intended to engage in a fair one-to-one combat, but Sugriva accompanied him for additional security in case the demon had any accomplices who might attack deviously. Not knowing the brothers’ honorable intentions, Mayavi shrank back in fear when he saw the awesome twosome charging towards him. Realizing that he was no match to their combined might, he turned around and fled.

Vali, knowing that the demon would disrupt the peace in the neighborhood if he were not taught a lesson, decided to pursue him, and Sugriva followed. Mayavi, trying desperately to shake off the brothers, ducked into a mountain cave that led to a mazelike network of catacombs.

Vali decided to pursue him in their dark cavernous hole and told Sugriva to guard the entrance, lest the demon evade Vali in the maze and try to escape. Sugriva implored Vali to let him join the dangerous subterranean search, but Vali refused and instead repeated his instruction. After his brother vanished into the yawning darkness, Sugriva waited for a long time, peering into the cave as far as the eye could see. He saw nothing and heard nothing till finally the cry of the demon resonated through the cave. Was it a cry of agony or of victory? Sugriva waited, straining and praying to hear some sound of his brother, but the cave remained deathly silent. When the deafening silence went on and on, Sugriva’s heart sank as he inferred that his heroic brother had been killed.

Sugriva felt torn between his desire to avenge his brother’s death and his duty to protect their kingdom from the deadly demon. If Mayavi came out of the cave, he might well be unstoppable. Sugriva pondered: Would he be able to overpower a foe who had already overpowered his more powerful brother? Deciding that discretion was the better part of valor, Sugriva devised an alternative strategy. He looked around till he spotted a giant boulder. Straining and sweating and panting, he moved that boulder till it sealed the cave. Feeling reassured that this would keep the demon at bay, Sugriva returned to the kingdom. With a heavy heart, he informed the anxiously waiting courtiers about the demise of their Valiant monarch and ordained a period of statewide mourning. After the mourning period ended, the ministers asked Sugriva to take up the role of the king, pointing out the absence of any other qualified heir. Still afflicted by memories of Vali, Sugriva resolved to carry on his brother’s legacy and accepted the royal mantle.

From Inseparable to Irreconcilable

A few days later, Vali marched into the palace, his eyes bloodshot. After a long search in the cave, he had found the demon. Being intent on ending the tiresome threat, Vali had wasted no energy in roaring while he slew the screaming demon. When he returned to the cave’s entrance, he was vexed to find a huge boulder blocking it. He called out to Sugriva, but got no response. Being exhausted due to the search and the fight, he couldn’t move the boulder. The absence of Sugriva and the presence of the boulder triggered in him a disconcerting suspicion: Might his trusted brother have connived to lock him in the cave?

Vali needed several days to regain his strength and come up with a plan to move the boulder. The more he struggled, the more his suspicion grew. Surely the boulder was too big to have been moved by the wind or other natural forces. And even if somehow it had been moved naturally, surely it couldn’t have so precisely closed the cave.

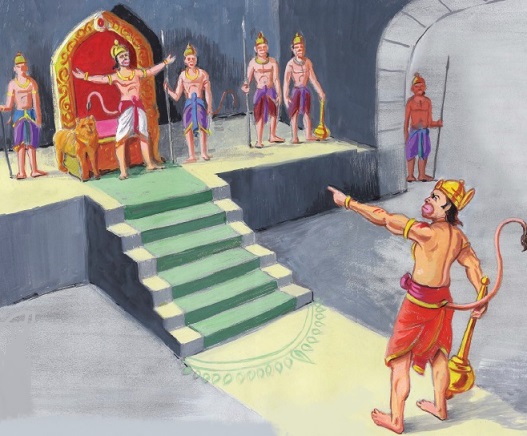

When Vali finally forced his way out, he raced back to his kingdom, filled with doubts about his brother. When he saw Sugriva seated on the throne, he felt his suspicion confirmed. Enraged, he pounced on Sugriva, whose elation on seeing Vali alive quickly gave way to dismay. Sugriva tried to explain the situation, but Vali was too furious to hear anything and simply pounded Sugriva with his thunderous fists. Sugriva was devastated to see the loathing in his beloved brother’s eyes. The thought that his brother had not only suspected but also convicted him hurt Sugriva more than the blows raining down upon him. Having no heart to fight back and hoping that he might have a better chance to clarify later when Vali had cooled down, Sugriva fled from the palace and the kingdom.

Seeing Sugriva flee reinforced Vali’s conviction that his brother was guilty. Otherwise, why would he have run away like this? Having thus judged Sugriva as a traitor, Vali’s self-righteous mind goaded him to pursue and persecute his brother even in exile, lest he hatch another coup.

The hapless Sugriva fled far and wide, but Vali chased him relentlessly. Finally Sugriva found refuge right next to Kiskindha – in the Pampa lake area, in the vicinity of the hermitage of sage Matanga. Vali had once in a power-intoxicated show of strength flung far away the carcass of Dundubhi, a demon he had killed. The blood from that carcass had fallen on Matanga’s sacrificial arena, thus desecrating it. The angered sage, desiring to check Vali’s hubris, cursed that the monkey would die if he ever entered the vicinity of the hermitage.

In the safe haven created by Matanga’s curse, Sugriva lived in an uneasy peace, always fearfully looking out for any assassins that Vali might sent to do the work he himself couldn’t do. As Vali’s hostility showed no sign of abating, Sugriva gradually lost all hope of reconciliation. The two inseparable brothers had now become irreconcilable.

Attribution Error

Both Sugriva and Vali arrived at mistaken inferences – Sugriva about Vali’s death and Vali about Sugriva’s treachery. If we consider the information available to them, they had both made reasonable inferences. The difference between them was that Sugriva had little opportunity to test his inference – the possibility of Mayavi coming out was too hazardous. But Vali had abundant opportunity to test his inference – being stronger, he could afford to give Sugriva a hearing. Moreover, Sugriva was no untrustworthy demon, but was his upright brother – and a brother who had served him faithfully as a right-hand man for many years. Due to both his relationship and his track record, Sugriva deserved a proper hearing before being judged. Unfortunately, Vali was too sure of his reading of the situation and felt no need to seek any clarification.

Vali succumbed to a common human error, which psychologists call an attribution error. When we see others behave in an inappropriate way, we tend to attribute that behavior to their internal character flaws, not their external extenuating circumstances. Thus, when we see others overeating, we judge them as gluttons. But when we ourselves overeat, we tend to be much more charitable in attribution: “I had not eaten for so long.”

We succumb to attribution errors because of a dangerous combination of haste and overconfidence. When faced with the unexpected, we want to understand it quickly; and once we come to an understanding, we hold on to it, thinking, “I am so intelligent – how could I be wrong?”

But if we are truly intelligent, we will consider the possibility that we may be wrong. After all, the ways in which things happen in the world are complex. And even more complex are the ways in which people think. So determining what makes them behave in particular ways is not easy. Yet when we know something about others, we presume that we know enough to figure out their behavior – a presumption that often blinds us to our biases and blunders. Rather than falling prey to such presumptions and arriving at snap judgments, we can do better justice to our intelligence by giving others the benefit of doubt and open-mindedly hearing their side of the story.

Due to his haste and overconfidence, Vali succumbed to judging Sugriva without understanding – a surefire recipe for ruining relationships. And sure enough, their relationship soon lay ruined.

Rama’s Intervention – Martial and Verbal

Fast-forward to several years: Rama entered the scene and entered into an alliance with Sugriva. As a part of their pact, he promised to correct the wrongs that Vali had done to Sugriva. At Rama’s behest, Sugriva challenged Vali to a fight. And when the two brothers were fighting, Rama, after an initial abortive attempt, shot Vali with a lethal arrow.

We may question the morality of Rama’s action, as did Vali himself while lying on the ground, mortally wounded. In reply, Rama gave various reasons centered on the point that a sinful aggressor can be killed by any means. Vali had committed multiple acts of aggression against his own brother: attacked with murderous intention, stripped him of all his wealth and even taken Sugriva’s wife Ruma as his own wife. For an older brother to seize the wife of his younger brother was a grievous sin, almost akin to incest. Due to all this unwarranted aggression, Rama declared that Vali deserved nothing less than capital punishment.

The analysis of this reasoning can be an article in itself. For our present purpose, it should suffice that Vali found the reasoning convincing. If the plaintiff in a case of perceived injustice pronounces after due discussion and deliberation that no injustice was done, we too can accept that pronouncement – after all, the plaintiff knows more and feels more than us.

After making his case, Rama deferred the judgment to Vali: “If you think I have acted wrongly, I will withdraw the arrow and restore your life and strength right now.”

Vali, his hubris destroyed doubly by Rama’s arrow piercing his chest and Rama’s arrow-like words piercing his presumptions, pondered his actions and recognized their wrongness. He humbly replied that despite his many misdeeds, he had been causelessly blessed to get the priceless opportunity to die in the auspicious presence of Rama – an opportunity that he didn’t want to pass over just for a longer life. He further confessed that for long he too had felt that he might have wronged Sugriva, but his pride hadn’t allowed him to consider that feeling.

Deathbed Reconciliation

With his last few breaths, Vali solaced his sobbing wife Tara and his grieving son Angada. He asked them to hold no grudges towards Sugriva, but to live peaceably under his shelter. Then he turned towards Sugriva, requesting him to bear no malice towards Tara and Angada, but instead care for them.

Seeking forgiveness from his brother and wanting to make amends, Vali took out the jeweled necklace that Indra had given him. That celestial necklace came with the blessing of protecting the life of its wearer. In fact, it was this necklace that had kept Vali alive for so long even after being mortally wounded by Rama’s arrow. What father wouldn’t desire such armor for his son? Just as Indra had given the necklace to his son, Vali too would have been entirely justified in giving that necklace to his son. But he gave it to Sugriva, thus expressing through his actions the deep remorse that he had not the energy or the time to express in words. As soon as the necklace slipped out from Vali’s hands, his soul slipped out of his body.

Having heard his brother’s heart-wrenching words and seeing him fall back, motionless and silent, Sugriva broke down. This was the elder brother he had known and loved and missed for so long – and would now miss forever. Being overwhelmed with regret for having instigated the killing of such a brother, Sugriva censured himself and resolved to atone for his sin of fratricide by ending his life with that of his brother.

Rama and Laksmana consoled Sugriva with gentle words, reminding him of his duty to his family and his citizens. Sugriva pulled himself together, ordered the grieving monkeys to arrange for a royal funeral for their deceased king, and began a second period of mourning for his brother.

AAA: Three Steps to Reconciliation

The story of Sugriva and Vali defies simplistic contours of good versus evil. Both brothers were virtuous, but they were ripped apart for life due to one unfortunate misjudgment by the more powerful, more impetuous sibling. What could have been a happy story of fraternal affection became due to one unclarified misunderstanding an unhappy story of fraternal animosity that ended in heartbreaking fratricide. Thankfully, their unhappiness was reduced by Rama’s intervention, which brought about a pre-mortem reconciliation.

We too can reduce the unhappiness in our relationships by internalizing the critical lesson from this story – never judge without understanding. And if we have already judged others without understanding them, we can seek reconciliation, as did Vali. We can tread the path to reconciliation using three A’s: Acknowledge, Apologize, Amend.

1. Acknowledge: In those of our relationships that have gone sour, we can honestly introspect and humbly hear from others to check if we might have been more at error than we have believed. If we come to know of our error, we need to acknowledge it, as did Vali after hearing from Rama.

2. Apologize: Just as arrogant words of judgment can hurt, humble words of rapprochement can heal. We can take huge steps in rebuilding relationships by apologizing like Vali for the wrongs we have done, knowingly or unknowingly.

3. Amend: Actions speak louder than words. Just as Vali gave his necklace to Sugriva, we can do whatever is best possible under the circumstances to correct, or at least mitigate, the consequences of our misjudgment.

Vali required the jolting arrival of death to put aside his pride and make up for his misjudgment. Hopefully, if we meditate on his story and learn from it, we can make up long before such an extreme jolt.

Caitanya Carana Dasa is the associate-editor of Back to Godhead (US and Indian editions). To read his daily Bhagavad-gita reflections, please subscribe to Gitadaily on his website, thespiritualscientist.com.