Hearts brighten when devotees deliver nourishing spiritual

food and the Lord's holy names to villages of South Africa's largest tribe.

SINCE MY ARRIVAL IN South Africa [January 19, 2002], my Indian disciple Laksminatha Dasa has been inviting me to take part in one of his daily Food for Life programs. For more than five years he has practically single-handedly cooked and distributed over fifty thousand plates of prasadam each week in the rural areas north of Durban. Known as KwaZulu-Natal, the region is inhabited by Zulus, the largest tribe in South Africa. Many Zulus live in utter poverty. Knowing that crime is rampant in the area, and that the presence of white people in the South African townships is not appreciated by those who suffered under apartheid, I hesitated to go.

Last month, Laksminatha's Food for Life van was hijacked at gunpoint in broad daylight. He had stopped to give some prasadam to a few young children on the side of the road when three men pulled up in a car, jumped out, and aimed an AK-47 at him while demanding the keys to his van. Laksminatha got out of the van slowly and stepped to the side. The men jumped in the van and sped off with a quarter ton of prasadaminside. When the police found the van five hours later in a nearby township, it had been stripped of everything the engine, doors, windows, tires, and even the prasadam.

Since then another group of men tried to hijack his new van. He was driving through a township when a gang blocked the road. Several men came forward and again demanded the keys to the van. Not seeing any weapons this time, Laksminatha refused.

"I'm feeding your people. Why do you want to stop me?"

One of the men replied, "Where do you get the money to feed us?"

"From God," Laksminatha answered.

"Why doesn't God take care of me?" the man shot back.

Laksminatha screamed at him, "If you call out to Him, maybe He will. Why don't you chant Hare Krsna!"

Startled, the man stepped back and said to his friends, "Let him go."

Laksminatha drove off, but he stopped a few hundred meters away.

Taking the big pots from the back of the van, he yelled, "Hare Krsna! Come and get prasadam!"

Soon several hundred people gathered with bowls in their hands to receive the Lord's mercy.

His boldness and determination have made Hare Krsna a household word among the Zulus. Wherever you drive in the greater Durban area, little Zulu children are often seen begging at stop lights. Whenever a devotee drives up, they start jumping up and down excitedly, calling out, "Hare Krsna! Hare Krsna!" But instead of asking for money, they ask for prasadam. Their enthusiasm alone is evidence of Laksminatha's service.

Once Srila Prabhupada was walking on the beach in Mumbai with some of his disciples. At one point, a little girl walked by and with folded hands said to Srila Prabhupada, "Hare Krsna!"

Srila Prabhupada smiled, turned to his disciples, and said, "You see how successful our movement is?"

Confused, one devotee asked, "Successful?"

"Yes," Srila Prabhupada replied, "if you take just one drop of the ocean and taste it, you can understand what the whole ocean tastes like. Similarly, by this one girl greeting us with Hare Krsna, we can appreciate how far the chanting of the Lord's name has spread."

Safe With Sergeant Singh

A few days ago, wanting to reciprocate with Laksminatha's service, I agreed to accompany him into a Zulu township. The next morning, I was napping after the temple program when I heard a knock on my door.

Half asleep, I called out, "Who's there?"

"Sergeant Singh. Durban Police," came the official reply.

Still a little jittery about the idea of going into a Zulu township, I jumped up and answered the door.

"Oh, Sergeant Singh, thank you for coming. Would you like to come in for a moment?"

"No, Swami," he replied. "Laksminatha and the boys are waiting for us at the Food for Life kitchen. Let's go."

Grabbing my chanting beads, a shoulder bag, and my danda [renunciant's staff], I followed Sergeant Singh to his police car. He opened the trunk and put my bag inside. Before closing it, he pulled out his service belt, which held a Tanfoglio 9mm semiautomatic. Taking the gun out of the holster, he checked the chamber and clip to see if it was full of ammunition.

Looking at me he said, "It holds fifteen rounds. But don't worry, I probably won't have to use it. The Zulus in the townships love Laksminatha. He's got carte blanche to go into the African areas where no Indian or white man would dare go. But resentment against the former apartheid regime still runs deep in the townships, and we can't take any chances. Since he was hijacked a couple of weeks ago, we go with him anytime he calls us. You've always got the oddballs out there and the desperate. They're mighty poor folk."

With the lights flashing on top of the police car, we pulled out of the temple complex with Laksminatha and a few other Indian boys in his Food for Life van behind us. Another car with four women devotees also followed.

Sergeant Singh smiled and said, "A police car with flashing lights gives an air of importance to the mission, don't you think?"

"Yes, officer," I replied. "You're welcome anytime."

We drove north out of Durban for an hour through sugarcane fields to Kwa Mashu, the native land of the Zulus. After another hour, we pulled up along a ridge overlooking a beautiful valley.

Sergeant Singh said, "A few hundred kilometers north of here the Boers defeated the Zulus in the Battle of Blood River in December of 1838. The river was previously called the Ncome River, but so many Zulu warriors were repulsed into the river and killed in that battle that the water turned red. This huge valley once provided the Zulus who lived here all they required for their livelihood. Now many of them have left to live in cities like Durban and Johannesburg. The land lies barren, and those who are left live in shacks."

As I surveyed the ridge sloping down into the valley, I saw small dwellings assembled from all sorts of material planks of wood, and sheets of plastic, pieces of old corrugated metal all bound together in various shapes and forms. I couldn't imagine life inside such shacks.

Sergeant Singh continued, "To many nineteenth-century Europeans, the Zulu epitomized the romantic notion of the 'noble savage.' While they may indeed have been noble, they were far from savages. Their warfare was characterized by iron-willed discipline, and their society by a sophisticated culture influenced by the environment in which they lived. Even though most Zulus have become Westernized, many of them adhere to their traditional customs, rituals, and ceremonies. Just look over there, coming up the path. That's an isangoma a traditional healer."

I looked at the path coming up the valley and saw a stocky woman with a headdress of hundreds of colored beads.

"She's the village doctor," said Sergeant Singh. "Look closely and you'll see a dried goat bladder plaited into the beadwork of her headdress. She's also carrying the traditional wildebeest-tail fly whisk. They sayisangomas can communicate with the village ancestors. They're masters of a form of natural medicine using a vast range of herbs, plants, and roots."

As she walked by our car I smiled at her, but she didn't seem to notice me.

"They're often in a kind of trance," said Sergeant Singh. "Unfortunately, the original Zulu culture still exists only here in the rural areas. In the cities, they are prone to drinking, fighting, and stealing. In Durban the crime rate among Zulus is escalating out of control, and over half of them have been found to be HIV positive."

"Good candidates for Lord Caitanya's mercy," I said.

Drawn By The Beat

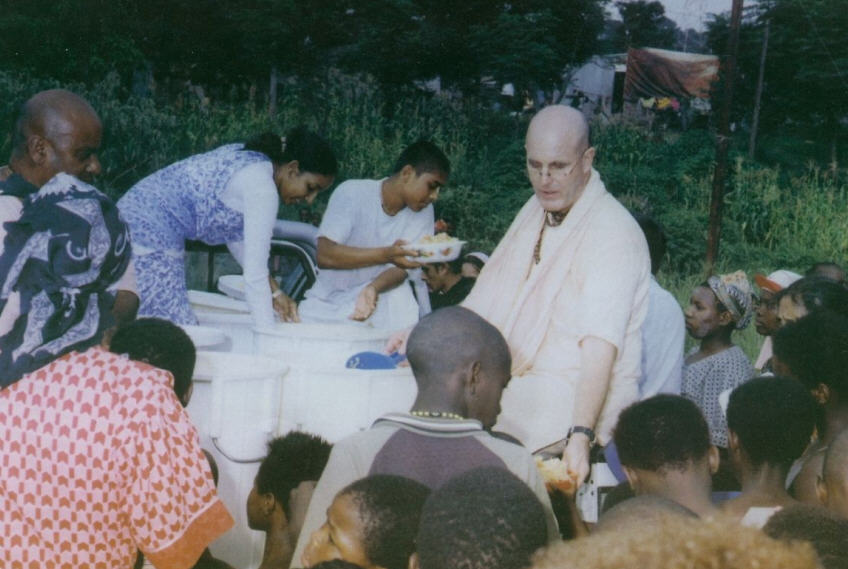

Laksminatha's van, parked behind us, came alongside, and Laksminatha, a big smile of anticipation on his face, said, "Let's do harinama [chanting] from this spot down into the valley. I'll drive the van in front of thekirtana party, and Sergeant Singh can follow behind. We'll distribute prasadam at the bottom."

Picking up a mrdanga drum, I adjusted the strap and began warming up, playing a few beats on the heads.

"When we get there," I asked Lak sminatha, "how will the people know we're distributing prasadam?"

He replied, "This is not the first time we've been here. The sound of your drum will announce everything. Just look what a few beats have done!"

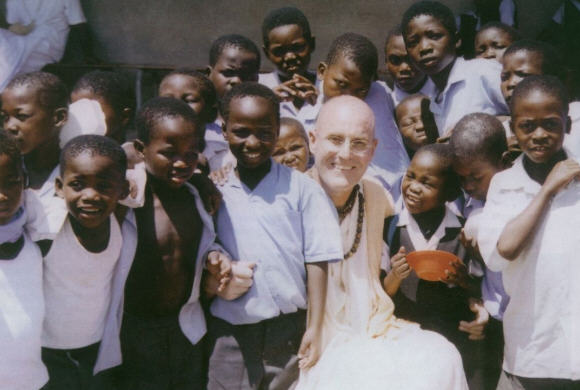

Turning my head, I was startled to see hundreds of Zulu children, most of them half naked, running toward us along the dirt road leading into the valley. They had all kinds of receptacles in their hands for gettingprasadam bowls, cups, pots, dishes, and even big garbage bins. They were running and calling out, "Hare Krsna! Hare Krsna! Hare Krsna!"

I kept playing the drum and began singing Hare Krsna. The three boys who had come in Laksminatha's van joined in playing karatalas [cymbals]. Within moments, all the children had surrounded us. Immediately swept up in the kirtana, they began dancing.

Sergeant Singh said, "They love the drum beats. It's in their blood. Wait till you hear them sing. Zulus have beautiful voices!"

Hearing that, I asked the kids, through a small sound system, to repeat the maha-mantra after me as I sang. As they all responded in unison, I was struck with wonder. They really did have beautiful voices. Harmonizing naturally, they sounded like an experienced choral group.

"This is a kirtana man's paradise!" I thought.

Following Laksminatha's lead, we all began to move down the road into the valley.

As he went to his car, Sergeant Singh whispered in my ear, "It's all very fun, but remember that you're an uninvited guest in a hostile environment. And you're white. Don't go off the beaten track, and always keep your eyes on me."

As we chanted, the Zulus in the shacks along the way started lining the road. Most smiled and waved, but I noticed some hard glares among the older youth. I kept looking back at Sergeant Singh, and as I did he would flash the blue lights of his police car.

I kept the kirtana going strong, playing the drum as hard as I could and chanting loudly. The sound reverberated off the nearby hills, announcing our descent into the valley. Although there may have been some risk going into that shanty town, I was in bliss. The kids were responding to the kirtana like nothing I'd ever seen. It may have been in their blood, as Sergeant Singh had said, but the fact was that for the time it took us to get to the bottom of the valley, they were in Lord Caitanya's sankirtana party, becoming purified, dancing and chanting Hare Krsna in delight.

As we went along, more children joined us, spontaneously coming out of the shacks with an ever-expanding assortment bowls and dishes. Some were so poor they had only cardboard boxes from which to eat. But every one of them was swept up in the nectar of sankirtana. The happy mood contrasted with the dirt and filth of the township. Garbage lay everywhere, and an open sewer often crossed the dirt path we were following.

It was also very hot and humid. As the sun beat down on us, I lamented that I hadn't brought a hat. After an hour I was exhausted, but tasting so much nectar with the huge crowd of children that I couldn't stop.

Finally, two hours later, we reached the bottom of the valley, where hundreds more people were waiting for prasadam. I kept the kirtana going, though, as the children couldn't seem to get enough. They kept dancing madly, and a few of them even rolled about on the ground.

Eventually I brought it to a close, and they all swarmed around me. They were speaking excitedly in Zulu, of which I couldn't understand a word.

Sergeant Singh smiled and said, "They say they want more kirtana."

Because I didn't continue, they spontaneously started chanting, "Zulu! Zulu! Zulu!"

I thought, "Oh, I'd better bring them back to the transcendental platform."

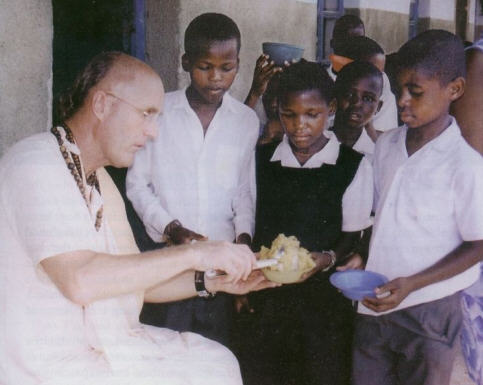

I told Laksminatha to open the van and start distributing prasadam.

Stampede For Prasadam

As he opened the doors, there was a stampede of children toward the van. Several of the Zulu men stepped forward and commanded the children to form lines and wait patiently. After a few tense moments things were under control, and I jumped inside the van to help distribute prasadam.

As I dished out the kicchari, rich with butter and various vegetables, the children kept asking for ever larger portions. After an hour, a big group of children motioned to me to come and sit with them on the grass. I got down from the van and went over with Sergeant Singh.

There were well over a hundred children sitting tightly in a circle, and as I sat down they all pressed forward to be near to me. When I noticed that most of them were suffering from one form of skin disease or another ringworm, impetigo, scabies I moved back a little.

All eyes were on me. At first they were silent, then one girl at the back said something, and the young boy closest to me reached out and ran his index finger down my arm. Holding up his finger, he shook his head and laughed. At that, all the children started laughing. Sergeant Singh was also laughing, and I asked him what was so funny.

"The little ones have never been this close to a white man before. They thought you painted yourself white," he said. "It's a custom among Zulus to sometimes cover themselves with a whitish cream. It's seen as a sign of beauty."

Then the boy proudly held up his black arm and, pointing to it, started chanting, "Zulu! Zulu! Zulu!" Suddenly all the kids started chanting the same thing.

I interrupted and asked the kids to be silent for a moment. With Sergeant Singh translating, I tolded them how actually we're not these bodies but our real identity is the soul inside, which is an eternal servant of God. They all stared back at me with blank faces, and I realized I wasn't going to get far trying to impress upon these young Zulu children even the ABCs of Bhagavad-gita. But by their enthusiasm for kirtana andprasadam, they had already proven themselves worthy of Lord Caintaya's mercy. So I picked up the drum, and even before I started playing it they were already moving their bodies to an expected beat. When several of them called out "Hare Krsna," the rest quickly followed.

Soon we were back in the spiritual world, chanting and dancing without cessation hundreds of small black bodies jumping and twirling in bliss. Many of the children's parents were on the side, also moving to the sound of the mrdanga and chanting the holy names. I thought how Lord Caitanya's saõkirtana movement is indeed the perfect formula for developing love of God in any part of the world. Nearby, just over 150 years ago, fierce battles for land took place between Europeans and Zulus. Now, by the mercy of Lord Caitanya, white men and Zulus were happily dancing together, their combined voices echoing the holy names of God throughout the valley.

After a while, Sergeant Singh caught my eye and motioned that the sun was setting. As much fun as we were having, it was too dangerous to stay in the township after dark. I reluctantly finished the kirtana and got into the police car. A multitude of sad faces looked on as we ascended the hill.

"I can't remember the last time I enjoyed a kirtana so much," I said to Sergeant Singh. "I'll never forget these kids."

"They'll probably never forget you either," he said. "You'll always be welcome back, and you won't need me next time. There's plenty more work to be done here, Swami. There are ten million Zulus in KwaZulu-Natal, and they all have sweet voices!"

One who is untouched by any piety, who is completely absorbed in irreligion, or who has never received the merciful glance of the devotees or been to any holy place sanctified by them will still ecstatically dance, loudly sing, and even roll about on the ground when he becomes intoxicated by tasting the nectar of the transcendental mellows of pure love of God given by Lord Caitanya. Let me therefore glorify that Lord Caitanya Mahaprabhu.

Prabodhananda Sarasvati, Caitanya-candramrta 1.2

His Holiness Indradyumna Swami travels around the world teaching Krsna consciousness. In Poland each summer he oversees dozens of festivals. Since 1990 these festivals have introduced Krsna to hundreds of thousands of people.

Adapted from the unpublished Diary of a Traveling Preacher, Volume 4. To receive chapters by e-mail as they come out regularly, write to indradyumna.swami@pamho. net. (Volume 1 is available from the Krishna .com Store. Please see page 64.)

To know more about Indradyumna Swami, visit www.indradyumnaswami.com