Computers Put the Byte on Humanity

Will the personalization of computers bring the depersonalization of you and me?

Late last year, for the first time ever, the editors of Time failed to name a "Man of the Year." Instead, they named the computer "Machine of the Year." All human competitors for the award from President Reagan down to Lennie Skutnik, who pulled a drowning woman from the freezing Potomac after the Air Florida crash were found wanting. Superceding all rivals, the computer reigned supreme.

True enough, computers have acquired a special place in modern society. Without computers, there'd be no intercontinental conference calls, no advanced television circuitry for a flawless Trinitron picture, no superaccurate cruise missiles. No pocket calculators, no Pac-Man, no Memory-writers or instantaneous bank transactions.

Still, one wonders just what makes the computer so great that Time would single it out over thousands of worthwhile nominees from the human race. After all, who gives computers their brains? Who puts them together? And when they break down, who fixes them? We know of no computer that is self-programming or self-repairing. In short, computers rely on man for every aspect of their existence. Man can live perfectly well without computers (and has for millennia), but computers can't exist without man.

But Time's editors weren't entirely off the mark. It's a peculiar fact that computers seem to acquire a life and "personality" of their own. Ever had the experience of sending a letter to, say, the phone company and receiving a reply from its computer? It's a little disconcerting to find out you're not dealing with a human being but with an impersonal thing that considers you another impersonal thing. And the way computers are proliferating, it won't be long before they're controlling nearly every aspect of our lives. Just imagine this scenario:

First, a computer sends you a two-million-dollar water bill. When you send back several desperate notes of protest to Central Waterworks, the computer classifies you as a troublemaker and dispatches the computerized robot police to your home. Although you activate your laserized home defense system, unfortunately it's tied into the city's central data bank. . . .

The computer police bring you before the android judge, who announces that his sibling system couldn't possibly be wrong and threatens to implant a few microchips in your brain for even suggesting such a thing. Such errors, he says, went out with Univac. He leaves you the choice of paying the bill, going to prison for three years, or doing alternative service in the Silicon Valley gulag.

Thus ends the perhaps not-too-futuristic case of John Q. Public vs. The Computer.

But the matter is serious. The personalization of the computer by Time and the phone company is the obverse of an even more sinister development: the depersonalization of human beings. Modern science, which has produced and refined the computer, has reached the conclusion that ultimately we are simply a combination of chemicals and that life is nothing more than the interactions of subatomic particles.

There is, however, an essential difference between machine and man. Unlike a computer, a human being has the self-contained powers of discrimination and will. A computer can't make any totally independent decisions: it must receive instructions from a conscious entity, a human being. But a human can make decisions without the aid of an outside agent.

We have this power of perception because within the material body of flesh, bone, blood, and so on is a conscious, spiritual observer, the soul. As living, spiritual souls we can feel love, anger, fear, and countless other emotions, and we can independently think and decide to act. As a conglomeration of dead substances like steel, copper, glass, and silicon, computers can only juggle information with great speed. So it's a little disappointing that Time awarded its 1982 prize to a machine. Any man (or woman, for that matter) would have been infinitely more qualified.

What I am suggesting is that the actual wonder is not in the machine but in man, and that the actual wonder in man is life. But who deserves the credit for creating the phenomenon of life? Life can't be explained by any mathematical formula or physical law. If a man could create life in the laboratory, he would certainly be the just recipient. But so far, all the scientists have done is take the essential life-containing ingredients from one place and transport them to another. No one has yet been able to create life from inert elements. So where does the credit for creating life go? To someone who has already created life, to the person who has created all the life that we see around us.

"Oh, no," you say, "now he's going to tell us about God." But what's the matter with that? Do you have a better explanation for life? If so, you'd rival the scientists now vying to be society's high priests. But just as I don't think the scientists, with all their Ph.D.'s, can figure out where life comes from, I don't think you can either.

I'm not asking you to accept my explanation simply on blind faith. Nor is it actually my explanation. It's the explanation of the Vedic literatures of India, the Sanskrit texts that form the oldest and most comprehensive body of spiritual and physical knowledge in the world. These books, which are available in English translation from ISKCON Educational Services, provide thorough, scientific answers to the question of the origin of life and the universe. I encourage all of you to investigate on your own and see whether the Vedic literatures can answer these questions for you, as they have for millions of people for thousands of years.

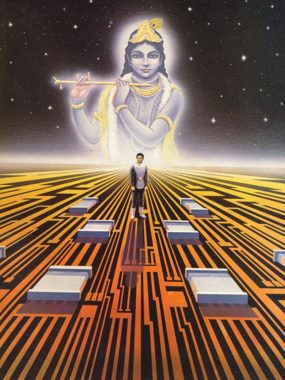

Perhaps Time could have named the "Person of the Year" instead of the "Machine of the Year" or even the "Man of the Year." And if they had made an exhaustive study, they would have had to conclude that the real "Person of the Year" is God, Lord Krsna. It is He alone who is the source of all life and who has created the entire universe by His innumerable inconceivable potencies. Who could be a better "Person of the Year" than God, on whom everything rests, the Bhagavad-gita affirms, "like pearls strung on a thread"?