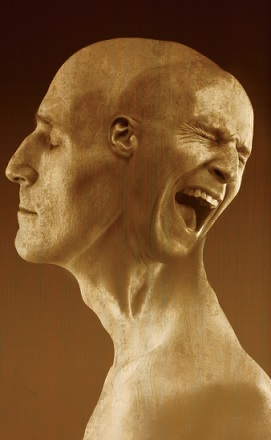

Being our closest companion, the mind needs to be constantly monitored, under the lens of divine intelligence

The word mind, as used in common parlance, connotes many things including awareness, intellect, memory, attention, intention and determination. Despite its familiar connotations, what the mind actually denotes remains vague and elusive. This is evident in logical positivist philosopher A. J. Ayer’s refusal to study the mind because "it has no locus." Translated to nonjargon, he essentially admits not knowing where or what the mind is.

The Bhagavad-gita, however, gives a clear understanding of the mind, placing it an intermediate level within a three-level model of the self:

1. The body is our visible material covering that we feed and dress, and normally identify ourselves with.

2. The mind is the subtle material mechanism that interfaces between the soul and the gross material body.

3. The soul is the essence of who we are – it the source of the consciousness that makes the inanimate body and mind seem alive.

Whereas some thought systems conflate the mind and the soul, Gita wisdom clearly differentiates the two: the soul is the root of consciousness, whereas the mind is the route of consciousness. The mind is the medium through which the soul interacts with the body and the world outside. The soul is conscious, whereas the mind, being material, is not – it merely reflects the soul’s consciousness.

Channel of Distraction

To better understand how the mind shapes the soul-body interaction, let’s use a computer metaphor. We can compare the body to the hardware, the mind to the software and the soul to the user. Stored in the mind are impressions of past pleasant and unpleasant experiences. These impressions condition it to certain patterns of functioning that over time become its default script. This script determines its ideas of what needs to be done for getting pleasure or avoiding trouble. Unfortunately, much of this script is distorted and distorting. The mind imagines pleasures where there are none or exaggerates insignificant pleasures till they seem irresistible. And it imagines problems where there are none or exaggerates inconsequential problems till they seem insurmountable. By thus distracting our attention from important tasks to unimportant or even unnecessary ones, the mind drains our energy.

That’s why we can’t just outsource our tasks to the mind and expect them to be done. We need to mind the mind, that is, we need to act as hands-on monitors, terminating those thought processes that take our consciousness in unwanted directions. Pertinently, the Bhagavad-gita (6.26) urges us to use our intelligence to restrain and refocus the mind whenever it wanders.

To better understand how the mind dissipates our energy in false alarms, let’s consider another metaphor.

Aggravator of Worry

We know the story of the boy who cried wolf, misinforming villagers about a marauding wolf when actually there was no threat.

The mind does something similar to us when it goes into a hyper-anxiety mode. By magnifying small problems till they appear like colossal catastrophes, the mind cries wolf.

Actually, the mind does much worse than crying wolf – it also acts as the wolf. When faced with a problem, the mind runs off into the past to the crises we had undergone and imagines that history is about to repeat itself. Or it runs off into the future, painting grim pictures of the many things that may go wrong. Either way, it sabotages our capacity to function effectively in the present. And the present is the only time that we have – or will ever have – to do anything right, be it correcting a past error, preparing for a future complication or choosing a fresh action plan. But the mind depletes our presence in the present by devouring our consciousness. Thus it acts like a predatory wolf.

Because the mind is like the misleading boy and the marauding wolf rolled into one, it is the worst wolf. No wonder the Bhagavad- Gita (6.6) warns that the mind can, when uncontrolled, be our worst enemy.

The Distracting Companion

Significantly, the same verse states that the mind can, when controlled, be our best friend. This implies that we can control the mind.

To understand how we can control the mind, we need to remember that the mind can never take the steering wheel from us. The body is like a car and the soul, the driver. In our bodily car, we are always in the driver’s seat.

The mind is our default traveling partner sitting permanently next to us. It frequently proposes ideas of where we should travel and fabricates images of the pleasures that await us there. By its propositions and fabrications, it prompts, prods, pushes, pinches and punches us to fulfill its wanderlust. However, it cannot usurp us from the driver’s seat. So, it can only impel us – never compel us. That is, though the mind can push us, it can’t force us. We have the power to not just neglect it, but also counter and silence it.

Countering the mind, however, is not easy. That’s because the mind doesn’t just persuade us to obey it – it also makes us believe that its voice is our voice. The mind subtly and sinisterly causes us to misidentify with it.

To understand how it effects such misidentification, we can compare it to a ventriloquist.

The Ventriloquist

Ventriloquism is the art of projecting one’s voice so that it seems to come from another source, say, a dummy. Those unaware of ventriloquism mistakenly think that the inanimate dummy is speaking, but those aware can figure out what’s actually happening.

The mind is like a most crafty ventriloquist. While ordinary ventriloquists may perform a show for us to see, the mind makes us its show. Ordinary ventriloquists may project their voices to inanimate objects for entertaining onlookers, but the mind projects its voice onto us and makes us believe that its voice is our voice. Because we are often unaware of the mind’s insidious tactics, we fall prey to its ventriloquism and act out its selfish desires, assuming that they are our desires. Only later when the short-lived pleasure of acting out ends and the consequences start registering do we ask in dismay: "Why did I do that?"

How do we protect ourselves from the mind’s deceitful ventriloquism?

By stopping the mind when it is speaking in the second person ("You do this and enjoy") and not letting it take on the first person voice ("I want to do this and enjoy"). To understand this, let’s explore the ventriloquism metaphor further.

When ventriloquists make a dummy speak, they have to be present somewhere nearby; the voice can’t be projected over long distances. If onlookers are informed and alert, they can, as soon as they hear the dummy speaking, look around, spot the ventriloquist and say, "That’s you speaking." By thus catching the ventriloquism in the act, they can avoid getting deluded.

Similarly, the mind has to be in our vicinity before it can make us misidentify with it. Of course, ontologically speaking, the mind is always in our vicinity; it exists inside us. But functionally speaking, the mind is not always aroused and active with its nefarious schemes; it’s not always a ventriloquist in the act.

When the mind becomes captivated by some unhealthy fancy and wants us to act it out, it initially has to speak in the second person: "Why don’t you do that? You will enjoy it. You need a break; you need some fun." At this stage, we sense that something within us is prompting us towards some unwholesome indulgence. Though the voice may be insistent, we are still aware that it is different from us; the mind is still speaking in the second person.

However, if we listen to the proposals of the mind, we give it the chance to cast its ventriloquistic spell on us. With frightening swiftness, it projects its voice on us. Soon, sometimes in a matter of moments, the mind starts speaking in the first person: "I want to enjoy that." But because we have been taken in by its ventriloquism, we no longer realize that it is the mind speaking; we mistake its voice to be our own. Once we take ownership of the mind’s desires, then all our inner safeguards crumble and we end up doing something foolish or selfdestructive.

The Trajectory to Self-destruction

The Bhagavad-gita (2.61-62) delineates eight stages in the trajectory to self-destruction. Let’s understand these using an example of how a recovering alcoholic may relapse:

1. Contemplation (dhyayato): The alcoholic starts considering the prospect of drinking: "Look at that – doesn’t that look good?"

2. Attraction (sanga): He starts feeling that a drink will be enjoyable: "It’s nice – you can relax and enjoy."

3. Obsession (kama): He starts feeling strongly infatuated by it: "I want it – and want it now."

4. Irritation (krodha): He starts feeling irritated at anything that stops him from getting it: "Who can stop me from doing what I want?"

5. Delusion (sammoha): He gets completely confused about what is good and what is bad: "I don’t need anyone’s advice – I know what to do."

6. Oblivion (smriti-bhramsad): He forgets the hangover, the bondage and the misery that alcohol has caused in the past: "There’s so much pleasure here – why should I not enjoy?"

7. Stupefaction (buddhi-naso): He loses his intellectual capacity to discern before acting and decides to act on the spur of the moment: "I am going to drink right now."

8. Destruction (pranasyati): He falls headlong into a relapse and wallows in it till he wakes up with an awful headache and throws up in the washroom.

In the stages of contemplation and attraction, the mind’s voice keeps getting louder and more demanding. But it is still speaking in the second person: "Why don’t you enjoy that? It looks promising." From the stage of obsession, however, the mind starts speaking in the first person. We start identifying with its desire and thereafter start feeling angry at whatever obstacle blocks us: "Who can stop me from enjoying?" Hereafter, the mind’s ventriloquism makes a complete fool out of us; we cast aside our intelligence and binge, and thus get ourselves into trouble.

To protect ourselves, we need to be alert and catch the mind when it is speaking in the second person: "Ah! That’s the mind speaking. I am not going to listen to it." Though the mind may still push us, just by disowning it we can win a major part of the battle. And we can win the battle fully if we immediately focus on something engaging, illuminating, empowering. Once we get engrossed in something constructive, the mind’s destructive proposals can no longer allure us. Being starved of our attention, it is eventually forced to fall back, whimpering and defeated.

Move away from the mind – and move towards Krishna

To mind the mind, we need to:

· Distance ourselves from it and

. Distance the real situation from its distorted depiction of things.

Some ways to do this distancing are: deep breathing, meditating, journal-writing, praying and, most importantly, studying scripture with spiritual guides and chanting the holy names.

Scripture serves as a standard guidebook for human behavior. When we study scripture regularly, we become equipped with a ready reference point for evaluating the mind’s proposals and rejecting them whenever they contradict scriptural guidelines. As the import of scripture and its relevance in our daily lives may not be immediately apparent to us, we need the guidance of spiritual mentors, who can counsel us according to our specific situation.

The supreme scriptural guideline is to become devoted to Krishna , for that alone reinstates us on the spiritual platform of existence that is our eternal home. And moving closer to Krishna automatically moves us away from the mind, especially its distracting proposals. And as Krishna is allattractive, moving towards Him is much easier and sweeter than just moving away from the mind. Moreover, He being our greatest well-wisher, as the Gita (5.29) states, helps us by His omnipotent grace to ward off the mind’s unwholesome advances.

As Krishna is all-attractive, moving towards Him is much

easier and sweeter than just moving away from the mind

The best way to move towards Krishna is by chanting His holy names, because that divine sound offers us an accessible and relishable channel for raising our awareness to a higher, spiritual level of reality, thereby automatically moving away from the mind and its obsession with petty things.

Caitanya Caraëa Dasa is the associate-editor of Back to Godhead (US and Indian editions).