Transcendental Commentary on the Issues of the Day

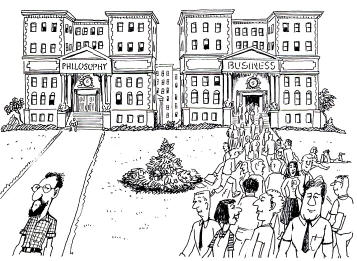

On December 12, 1986, the Wall Street Journal published the results of an attitude survey of college freshmen originally taken in 1967 and repeated in 1985. In 1967, 83 percent believed "it is essential or very important to develop a meaningful philosophy of life," and 44 percent believed "it is essential or very important to be well-off financially." In 1985, the answers appeared to indicate a reversal of attitudes: only 43 percent were more concerned about developing a meaningful philosophy of life, while 71 percent placed more emphasis on their economic development!

Were people more spiritually inclined twenty years ago, as these surveys seem to indicate? Actually, these statistics do not take into account economic changes of the last twenty years. Although the median income is nearly twice as much now as in 1967, the dollar buys much less. In more and more families both spouses work. People work all hours of the day and night, many businesses staying open very late or even twenty-four hours a day or seven days a week. Twenty years ago these were exceptions. People may be no less sensitive, intellectual, or spiritually inclined now, but for many of them earning a living has become harder and more complex. Generally, people postpone serious spiritual endeavors or inquiry into the higher purposes of life until they achieve economic stability. This helps to explain the differences between the answers in the 1967 and the 1985 surveys.

If we were asked those survey questions now, what would be our answer? Are we after more economic development or a satisfying, meaningful philosophy of life? Or do we want both? Is it possible to develop a meaningful philosophy of life without neglecting economic necessities according to our position and status? How can spiritual values be compatible with material values? To answer, one needs to analyze both.

The basis of economic development is easy enough to recognize it's work. After all, one has to keep body and soul together by working. To work according to one's psychophysical nature is known in Sanskrit as varna.

A meaningful philosophy of life depends on our state of consciousness how aware we are of ourselves and the world and universe before us. Our consciousness naturally expands as we mature: from awareness of mother, then father, siblings, friends, community, religion, nation, humanity, other living entities, and the world around us in general. The highest stage of consciousness is God consciousness, or, more precisely, consciousness of the Supreme Personality of Godhead. That consciousness is described and analyzed in the Vedic literature, especially Bhagavad-gita.

Although this higher consciousness is natural, like learning to walk, speak, or act, it is not automatic. Rather, God consciousness, or Krsna consciousness, is awakened by certain techniques, which can be practiced anywhere in the world even at home by anyone.

Initially, one may doubt that one can relate one's work to spiritual values. Owing to experience, one may conclude that to make spiritual progress one must give up everything considered material.

This misgiving is directly addressed by Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura (Srila Prabhupada's spiritual master) in his commentary to Text 61 of the ancient Brahma-samhita, or Hymns of Brahma. He formulates the basic question: How can one continue with worldly affairs if one is always engaged in the pursuit of spiritual happiness? And what would be the activities of such spirituality if one were required to withdraw from society?

In answer, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta explains that you don't have to withdraw. When worldly activities are performed as a basis for Krsna consciousness, they are considered subsidiary devotional, or spiritual, practices. In other words, one should begin spiritual life by considering how to organize one's worldly activities so that they are conducive to Krsna consciousness. One's worldly activities are favorable to Krsna consciousness when one meditates upon Krsna and obeys His instructions. In such a position one will not become lethargic about spiritual life even though engaged in working with agnostic or atheistic people.

Srila Prabhupada gives an example: Just as a married woman who has a paramour performs her household duties nicely so that her husband won't suspect that she is always meditating upon meeting her lover, one should do one's work conscientiously, never losing sight of the fact that one is a servant of Godhead, or Krsna.

If one's work becomes a means to such a spiritual end, then that work will eventually lose its material quality. Everything is originally spiritual because it comes from God, but when spiritual energy is covered by maya, or forgetfulness of God, it appears to be material. When so-called material things are used in Krsna's service, they regain their original spiritual quality.

Spiritual behavior or practices, technically called asrama, combine naturally with one's work, or varna. One who lives in this way is acting according to varnasrama, the system for spiritualizing one's life. The first stage of spiritual practices includes chanting the Hare Krsna mantra, studying scriptures, and serving others by passing on whatever Krsna consciousness one has understood. The purifying effects of these practices cause gradual detachment from such antispiritual habits as intoxication, nonvegetarianism, gambling, and illicit sexuality.

This is explained in the Bhagavad-gita (2.59): "Though the embodied soul maybe restricted from sense enjoyment, the taste for sense objects remains. But, ceasing such engagements by experiencing a higher taste, he is fixed in consciousness." Srila Prabhupada comments, "One who has tasted the beauty of the Supreme Lord Krsna, in the course of his advancement in Krsna consciousness, no longer has a taste for dead material things. . . . When one is actually Krsna conscious, he automatically loses his taste for pale things."

Thinking Of Grandpa

by Dvarakadhisa-devi dasi

My grandfather used to be the president of a railroad company. A tall man with a deep, booming voice, he commanded respect on the job and at home. He was the undisputed patriarch of my mother's German family, and we kids were awed by his somber presence. We loved him, though, because his deep chuckles and twinkling blue eyes emanated humor and affection.

Now he lies in a sterile hospital bed, defeated by illness and age. Nurses hardly a quarter his age bounce into the room to roll him over or poke needles into his withered arm. "Now, this might sting a little bit, Mr. Schmidt," they coo, just as he used to coo at his numerous grandchildren. He closes his eyes and prays that the end will come soon.

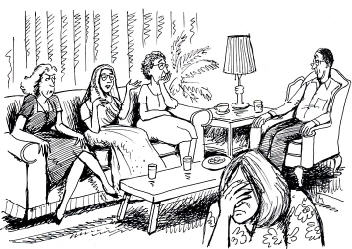

About thirty miles away my grandmother sits with our family in our living room, twisting her wedding band around her knobby finger. "He doesn't want to see anyone," she says. "And he doesn't want anyone to see him the way he is now. He can't move his legs. He's so weak he can't sit up, can't feed himself. He has the sweetest little nurse, but he won't even look at her. He's starting therapy now, but the doctors say his recovery will be slow because he's so depressed."

We listen, asking questions like "Do they think he'll ever walk again?" I think of my grandfather's large frame, wasted by old age and illness. I remember his expansive confidence and his kindness.

"I guess this is what it means to have a material body," I say with a sigh.

As soon as I say it, the room seems to chill, as if I had announced my grandfather's funeral plans. Mom shoots me a cold stare, and my grandmother seems ready to cry. Everyone else appears uneasy crossing and uncrossing their legs, pursing their lips, furrowing their brows. There she goes, they think, promulgating her sectarian religious views at this most delicate family conference.

Okay, maybe it was crass of me to bring up the grimmer aspects of human experience in such a matter-of-fact way. After all, it's not just any material body wasting away in a hospital bed it's Grandpa! To suggest some responsibility on his part for his intense suffering is a little bit too direct for my family's sensibilities.

It's just that they identify so completely with their bodies! I don't want to lecture them, but sometimes I marvel at the strength of their illusion. All of them have suffered through some bitter moments, and even the youngest children have been assaulted by health problems. But they manage to plug cheerfully along, smoothing the way with sympathy or intoxication, blithely ignoring the gradual deterioration of all they hold dear. Grandpa is dying in tremendous pain, yet they think life is wonderful.

As my grandfather lies longing for death's release, my family tries to devise methods to reawaken his zest for life. But what can they entice an eighty-year-old invalid with? Liquor? Girls? He's had everything that buckets of money could buy. Now when he thinks of his big house, his faithful employees, and the honor and respect he's received, he feels empty and sad. Nothing he accomplished in all those years is easing the pain of this: his body is falling apart, and he's finished. It's not the physical pain that's tormenting him; it's the mental anguish. Because now he sees . . .

Once my sister and I were laughing at a pudgy middle-aged lady with eyebrows painted across her forehead and piles of raven curls perched above her graying scalp. But in the middle of the laugh I suddenly felt sad. What was funny about this woman's ignorance? Of course she wasn't beautiful, but what was the difference between her illusion and my own? Anyone who accepts the material body as the self is a fool. She was a fool in her attempts to beautify her aging body. I am a fool as I worry over the wrinkles in the corners of my eyes. My sister is a fool as she ponders over what shade of lipstick to buy. And our foolishness isn't funny it's dangerous. This foolishness guarantees us immense suffering in this life, as Grandfather will attest, and when this body is through, we'll get another, and another. And the further we deviate from self-realization, the more miserable our bodies become.

Yet what can I say to my family to help them, if even my gentle reminder of the body's temporal nature brings about such consternation? I want to tell them that Grandpa's physical condition can only get worse. Can't we tell him about the transcendental nature of the soul? And what about Grandma? She hasn't much longer herself. And what about you and me. Dad? Is it too hard to hear that we're all going to die?

Since they're my family, and since I love them, I decide to try again.

"Now that Grandpa is so sick, we can help him come closer to God," I say to my grandmother.

She smiles in appreciation, but her eyes drift away. . . .