Descendents of a long line of South Indian deity carvers cast

the Panca-tattva deities according to strict scriptural guidelines.

As this year slid slowly into February and the cold mornings blurred into soft-sun days, winter began to shed its skin in Mayapur. The residents breathed a sigh of relief; weary from long months of heat and thick monsoon rain, they had welcomed the cold weather, but were now just as anxious for some sun-filled days with warm breezes. On a morning that woke lazily under a blanket of fog, an electric charge filled the atmosphere as word spread: "Sri Panca-tattva are coming today!"

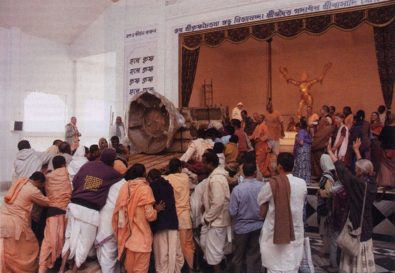

Devotees streamed out of the temple, through the main gates, and onto Bhaktisiddhanta Road, the main road that follows the Ganges into Mayapur. Their destination was the birthplace of Lord Caitanya (the yogapitha), one kilometer from Sri Mayapur Candrodaya Mandir. As devotees gathered at the gates of the yogapitha, where they would meet the deities, the tension increased. Finally, the distant sound of kirtana reached them. It was the chanting of hundreds of devotees who had gone on ahead and were now escorting the truck carrying the deities.

As the procession came into view, the sight was amazing colorful ags on bamboo poles danced in the air, held aloft by a stream of devotees who surrounded the heavy-load truck. Those waiting at the yogapitha fell to the ground, offering their respects to the precious cargo aboard the forty-foot flatbed. The smiling driver, Muruge-shan, had driven for five days and nights from Kumbakonam in South India.

The kirtana increased, the sound tumultuous, sweeping all into its irresistible embrace. From houses and shops, local villagers emerged, curious about the source of this wonderful celebration. Work stopped at the five-story construction site next to theyogapitha temple as laborers hung over balconies, their faces breaking into huge smiles.

As the truck made its way slowly along the narrow village road, Lord Nityananda's hand protruded from its careful packaging. It curved, gently and softly, towards the edge of the truck. One by one, devotees lined up to receive the first blessings and the loving touch of the most merciful Sri Nityananda Prabhu, His golden fingers caressing everyone.

As the truck turned into the back entrance of the Mayapur Candrodaya Mandir and rolled gently to a standstill, the cargo didn't budge; precious as it was, it was secured tight. No chances had been taken nothing, not even an earthquake, would shift it. For this special load was the Supreme Lord in His deity form Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu, along with His eternal associates Lord Nityananda, Sri Advaita Acarya, Sri Gadadhara, and Srivasa Pandita.

Fifteen-Hundred-Year Tradition

Sri Panca-tattva's journey began in the village of Swamimalai, where the deities were cast under the expert hands of Devasenapathy Stapathy and his sons, Radhakrishna and Srikand.  The family traces its lineage back to the era of King Chola fifteen hundred years, or three hundred generations. The king ruled the Tanjore district, and placed great importance in art, music, sculpture, and architecture. When he desired to build a temple, he brought families of sthapatis (deity carvers) from the north of India. The temple, which took thirty years to build and is still standing today, was the biggest temple in the world at the time. Its tower was constructed from a single stone, weighing eighty tons and covering the entire temple, so that the shadow of the temple never touches the ground. After the temple was completed, the sthapatis remained, and still today they make up the village of Swamimalai.

The family traces its lineage back to the era of King Chola fifteen hundred years, or three hundred generations. The king ruled the Tanjore district, and placed great importance in art, music, sculpture, and architecture. When he desired to build a temple, he brought families of sthapatis (deity carvers) from the north of India. The temple, which took thirty years to build and is still standing today, was the biggest temple in the world at the time. Its tower was constructed from a single stone, weighing eighty tons and covering the entire temple, so that the shadow of the temple never touches the ground. After the temple was completed, the sthapatis remained, and still today they make up the village of Swamimalai.

Before the deities were cast, there were many years of preparation. Bharata Maharaja Dasa, who was to play a major part in the deities' creation, began to study the Silpa Sastras, the scriptures covering deity making. He en-countered a major problem: Worship of Sri Panca-tattva is from the Bengali tradition, and no scriptures existed for their worship. So Bharata turned to the South Indian traditions but modified the deities' proportions according to the written records of the Panca-tattva's pastimes in Navadwip around five hundred years ago.

Still there were countless details to be resolved, including the height of the deities and their pose. Towards the end of 1997, the Sri Mayapur Project Development Committee (SMPDC) decided upon the poses from drawings submitted by Caitanya Candrodaya Dasa, an artist who worked in the SMPDC's London office.

Bharata Maharaja's study of the scriptures and his involvement with the sketching and the subsequent molding of clay models gave him a strong idea of how the deities would look. He worked strictly under the direction of Jananivasa Dasa, the headpujari (priest) at Mayapur. Jananivasa's instructions related to the mood and characteristics of each personality of the Panca-tattva.

"We didn't just have the deities carved according to some formula or computer-generated calculation," Bharata Maharaja said. "Jananivasa put the personality and mood into each deity; he captured the expressions that you see on each face."

"We didn't just have the deities carved according to some formula or computer-generated calculation," Bharata Maharaja said. "Jananivasa put the personality and mood into each deity; he captured the expressions that you see on each face."

Jananivasa would relay his directions to Bharata, who would then produce a clay model of the particular part of the body discussed. Then the artists would copy it and produce the final cast. In this way, the deities developed individually.

Recently, sitting behind the closed doors of the altar in the Panca-tattva temple and adding the finishing touches to the deity forms, Bharata Maharaja admitted that it was unavoidable that Western concepts would inuence the shape and form of the deities.

"Different cultures have different conceptions of beauty," he explained. "In African tribal traditions, for example, a long neck is considered beautiful. In South India, their concept of beauty is different from a Bengali viewpoint. So in this way, through the involvement of South Indian sthapatis and Western devotees, we have produced these deities."

Bharata Maharaja smiled as he looked up at the outcome."The ultimate result is uniquely beautiful."

A Needed Push

Towards the end of 2001, though, things had been at a standstill. Ganga Dasa and Bhagavatamrta Dasa, both long-time residents of Mayapur who were involved in the deity-casting project from start to finish, decided the time was right to get things done. They were keen to revive the project and see it through to the end.

Ganga told Bharata, "We thought we could just get on our motorbikes, ride down to South India, and get everything moving get these deities made!"

It was to take a lot more than that, but it was no doubt because of the involvement of these two devotees that things took a giant step towards completion. They once again approached Devasenapathy, who sent his eldest son, Radhakrishna, to Mayapur. Radhakrishna discussed the desires of the team and showed examples of his previous work. Because of Devasenapathy's ill health, the job was given to Radhakrishna and his brother, Sri-kand, and the fiberglass models of the deities were sent south to their workshop. When the father saw the model of Lord Caitanya, he approved, saying it was made according to the South Indian scriptures that guided his tradition. He gave the nod for the work to commence, telling his sons, "Take extra care with this work it's a special project." Sadly, Devasenapathy would not live to see the result: He passed away in 2002 before the casting began.

One of the main contributions to the deities' form from the South Indian tradition is the ornaments and intricate engraving on the bodies. This was one of the conditions that Devasenapathy made to Jananivasa that he would cast the deities as long as he could include these traditional ornamental carvings. He told Jananivasa this condition must be met; otherwise his entire line hundreds of generations would be cursed, since sthapatis never make deities without clothing. Jananivasa agreed. The result speaks for itself.

Bharata Maharaja was called to South India to oversee the refinements that were added at each stage of the carving.

"Every stage of the work saw changes made," said Bharata, "and every person involved added something. We didn't move backwards."

The preparations for the castings began, starting with puja (worship).

"The casting is not a manufacturing process," Radhakrishna explained. "Everything is done according to culture."

First, Radhakrishna and Srikand, along with their wives, invited brahmanas to the area where the casting would take place. Purification rites were performed during a fire sacrifice, and the brahmanas were asked to give their benediction that work would flow smoothly. This was followed by Go-puja (worship of the cow) and Tulasi-puja (worship of the sacred Tulasi tree). Finally, Agni-pujaworship of Agnideva, the god of fire was performed, as the process of casting is done under conditions of intense heat. Sixty to a hundred devotees performed kirtana continuously throughout the casting period.

In April 2003, Lord Caitanya was cast first, followed by Nityananda, then Gadadhara, Advaita Prabhu, and finally Srivasa. The casting of each deity was performed strictly according to astrological calculations. Auspicious days, hours, and minutes were chosen, as directed by scripture.

On the day of casting Gadadhara, heavy rain surrounded the area and threatened the workyard. Because of the intense heat of the liquid metal, not a drop of water can be mixed into the metal; such a mixture could result in small explosions capable of injuring those onsite.

Radhakrishna approached Jananivasa and said to him, "Maybe today there will be no casting."

A dose of mercy was needed, and it seems that Krsna gave it.

"While all around the sky was black and rain fell continuously," Ganga Dasa said, "the entire work area was dry."

Work continued day and night. When it was suggested that outside help be brought in to speed things up, the workers refused: No one but them was going to work on these deities! They increased their pace. Radhakrishna says that without Bhagavatamrta's pushing, the deities would never have been finished in time. Although the work was going on, Bhagavatamrta came daily, pushing harder and harder, encouraging everyone to work faster. He was the main force behind Sri Panca-tattva's arriving in Mayapur on time. He was anxious to share the excitement with devotees worldwide. His emails, sent hurriedly from South India, captured the mood that was prevalent as the deities prepared to leave for Mayapur.

A Well-Earned Title

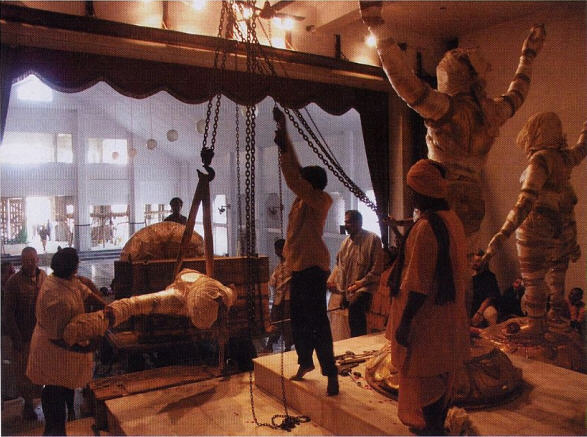

Loading the deities onto the truck and unloading them at the other end would prove to be another obstacle, which lasted several days. Along for the ride was Ravi Chandra, the chief engineer in charge of ensuring that the deities were taken care of properly and unloaded without damage.

The job was left in his capable and in the end, damaged hands. When Lord Nityananda was being worked on in December, He broke free of His ropes not once, but three times. The third time, Ravi put both his hands out to stop the deity from falling quite a remarkable feat, considering the deity weighs in at around two and a half tons. Somehow, Ravi's hands did the job, and Lord Nityananda was saved. But Ravi's left hand was trapped underneath the deity's left hand the same hand that reached out of the packaging and beckoned the devotees while still on the truck and required twenty-four stitches. He also broke a finger on his right hand. Regardless, he showed up for work the next day.

Refinements continued up to the installation. Radhakrishna was particularly thoughtful when asked if he was satisfied with the result.

"Ordinarily, when we began to work, our father would guide us. After finishing a job, we would ask his approval. This time, our father was not here, so we wanted to make this job better than anything we had done in his presence, so that we knew he would be pleased, wherever he may be."

He added that seeing the deities complete and watching the devotees' reactions to the first darsana (audience) was a moving experience for him.

"I was standing at the front of the altar, but when the doors opened and the devotees roared with delight, I was thinking I should have stood at the back, because I wanted to see the looks of joy on the faces of the devotees, to see their longing to see the Lord."

During the abhiseka (bathing) ceremony at the installation, which Radhakrishna describes as "the most grand abhiseka I have ever seen anywhere," he was amazed at the devotees' reactions: Tears of joy poured from their eyes, and their love for the deities was evident in their chanting and in their blissful faces.

When asked how he felt about leaving the deities in the care of devotees in Mayapur, Radhakrishna said, "Usually the father likes to see that the son is very well situated, not doing as well as the father, but better. Similarly, when I made Lord Caitanya and His associates, they became like my sons."

Radhakrishna pauses, choosing his words carefully. "When I saw how everyone was worshiping the Lord so nicely, with so much love, I was very happy."

He lifted the corner of his cloth, wiping the tears from his eyes.

"I can say with confidence, 'the son is doing very nicely.'"

It is evident that Radhakrishna is pleased with the outcome.

"I have made many deities before these, but only now, after making Lord Caitanya, can I say that I have earned the title 'sthapati.'"

Thousands of devotees worldwide will certainly agree.

Braja Sevaki Devi Dasi is a disciple of His Holiness Tamal Krsna Goswami. She is the author of three books, and her poetry has been published in Aus-tralia and Britain. She lives in Mayapur with her husband, Jahnu Dvipa Dasa.