The pioneering work of WWF-India (The World Wide Fund for Nature)

and Friends of Vrindavan

EACH DAY, KRSNA and the other cowherd boys used to go to the forest with the cows. Once, His friends became trapped by a forest fire, and they called in fear for Krsna to save them. Krsna's response was simple: He swallowed the flames and extinguished the fire, saving the trees, the cows, and the boys.

The enduring image of Krsna swallowing the flames of the forest fire symbolizes His promise to protect His devotees and the creatures of the Vrndavana forest. Krsna lived as a simple cowherd boy in the land of Vraja, the region along the banks of the Yamuna River between Delhi and Agra. Here, amidst lush forests, Krsna herded cows, played with His friends, and danced with the cowherd girls. In Vraja are Govardhana Hill, which Krsna once lifted, and the perfumed groves of Vrndavana, where He would meet Radha at night.

It is surely no coincidence that this unique vision of God as a cowherd boy who loves and protects nature is so beloved by Hindus. Indian culture has always seen nature as divine, for nature stands in relation to God. There is something magic about the vision of God surrounded by nature. It has charmed generations of pilgrims to come to Vrndavana in search of the divine flute player.

Yet today the sacred forests of Krsna in Vraja are fast disappearing. Starting in the early sixteenth century, to answer the needs of pilgrims, devotees built temples and, around the temples, guest houses and asramas. Eventually the town of Vrndavana came into being. Today it is home to seventy thousand people and the annual destination of two million pilgrims.

The town of Vrndavana is one of India's hidden gems a monument to thousands of years of intense spiritual experience and the arts and culture thus created. The sad truth, though, is that the growing influx of pilgrims has virtually destroyed Krsna's sacred groves. The town of Vrndavana itself is built exactly where Krsna once performed his famous rasa-lila amid thick groves of kadam, tamal, andchampak. In place of the old stands of trees are now acres of brick, concrete, and tarmac. In place of the cry of peacocks, the air is rent by the harsh sound of autos.

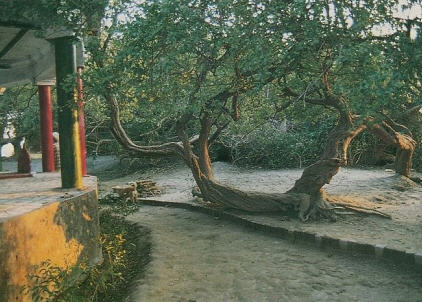

Nevertheless, the region of Vraja still abounds with sacred groves, the diminished remnants of the dense woodlands where Krsna roamed. Most of the woodland has been lost to a combination of commercial developments, reduced rainfall, falling water tables, and land clearance for farming. Worst of all is the loss of the age-old traditions of forest conservation that had been practiced for so long in India's villages. Along with the woodland have disappeared the stocks of groundwater that the trees kept beneath their roots. The woods have shrunk to a hundredth of their original extent. Now only small scattered groves, most an acre or two, dot the parched landscape of Vraja. These remaining islands of vegetation are now oases of shade, sustenance, and water for birds, animals, and humans.

Sacred Protection

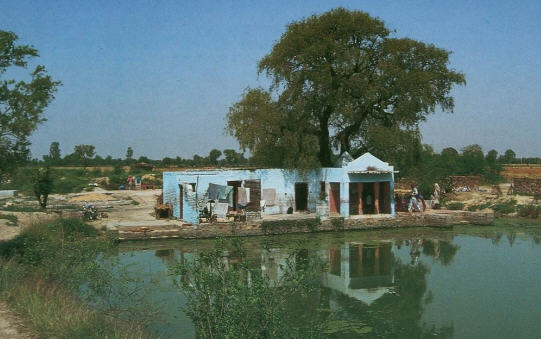

These groves have survived because of local religious traditions. For example, a few miles from Varsana, the birthplace of Radharani, is a grove of ancient kadam trees called Kadambkandi. Next to this grove is the small village of Navena. Local tradition has it that when the tyrant Kamsa sent demons to Varsana to persecute the villagers, Radha, the childhood sweetheart of Krsna, sought shelter in this grove. As a result it has remained a sacred spot, and here the kadam trees have stood, protected by the people of Navena, for thousands of years. The trees shelter a magnificent lake, broad and deep, which provides water for the villagers, shelter for many species of waterfowl, and a cooling dip for cattle and buffalo. This grove has survived where many others have vanished because of its link with Radha. That link has been a powerful charm of protection.

Many such groves are scattered across Vraja. Not far away, near the village of Nandagram, or Nandgaon, where Krsna lived as a boy, is a grove called Kadamter. The grove shelters two ponds and a small temple dedicated to Krsna, who came here as a small child to herd cows. When Krsna was very young He wanted to go out with the calves and His friends, but His mother, Yasoda, feared for His safety. So she let Him go only as far as she was still able to hear His flute. As long as she could hear His sweet flute-song, she knew He was safe. Kadamter is as far as He went. What a wonderful place to be! And no wonder this grove has survived for thousands of years, because it has been loved by the locals just as Krsna has.

Nearby is another grove, called Vrndakunda. Here two small ponds sit within a grove whose old trees have vanished, save one magnificent imli tree, under which nestles a small shrine to Vrnda, the goddess of Vrndavana. Vrnda has special significance to Vraja, because she presides over the forest pastimes of Krsna, communicating with the animals and plants through her parrot messengers. Vrnda is the choreographer of Krsna's Vraja pastimes. Vrndakunda was for years looked after by Madhav Baba, a local renunciant who lived there as caretaker. But sadly, in the last years of his life when he was suffering from ill health, Madhav Baba was unable to prevent many of the trees being lost. Before he died he asked devotees of ISKCON to continue to protect the grove. This they have done, forming the Vrinda Trust for that purpose.

Diminishing Trees

Although these and many other groves have survived thus far, their continued survival is under constant threat. With diminishing annual rainfall and falling water tables, the trees are not replenishing themselves as they used to. Farmers are becoming more bold, and the groves are no longer protected from encroachment and the ravages of grazing animals especially the numerous flocks of goats that annually pass through the region on their way to markets in Delhi. Property developers and land disputes are a major threat. Every year groves are being lost forever. Once a grove with its ancient trees is gone, it is impossible to bring back.

These surviving groves must be protected, and with them the wildlife and culture they nourish. Each year large numbers of pilgrims traverse Vraja, visiting many of the groves. Each year they find fewer trees. One day people will wake up to this disaster and wonder how it could have been allowed to happen. To re-create such sanctuaries would be almost impossible, but to save the ones already there, and to ensure their regeneration, requires only water and enclosures, and encouragement and support to the local communities.

A series of simple projects to protect the groves is starting. The essence of the projects is to form alliances with the village people and support them in preserving their own long-term interests. The villagers need no convincing, only support and encouragement.

Projects

Some of the projects are under the banner of the WWF Vrindavan Conservation Project, and others are supported by Friends of Vrindavan (FoV). Devotees of Krsna started FoV in 1992 to raise support for the groves of Vraja and campaign for their protection. At present FoV receives most of its funds from volunteers in England and the U.S.A., through its annual sponsored cycle ride, the Yamuna Cycle Expedition. Riders pay to come to India and cycle from the Himalayas down to Vrndavana, following the course of the sacred Yamuna River. They raise sponsorship from friends and workmates, and this sponsorship is donated to FoV. In the longer term, FoV also plans to raise support in India.

Fov has started a pioneer project at Manasarovar, in partnership with WWF-India. Manasarovar is a beautiful wetland grove and bird sanctuary a few miles from the town of Vrndavana, on the opposite bank of the Yamuna River. Here the lake was drying up and overrun by water hyacinth and pollution, and the trees were disappearing. Now a team of volunteers, backed by trained helpers and local village councils, are reversing the trend and ensuring the survival of Manasarovar. According to local tradition this sarovar, or lake, was formed of the tears of Sri Radha, while in an intensely emotional state of "wounded love" (man). Pilgrims come here to worship the image of Radha, who stands alone in the small temple.

WWF and Friends of Vrindavan have sacred grove projects underway in places in Vraja such as Ral, Baelvan, Basanti, Naradkund, and Manasarovar. Many more are planned. In addition, the WWF Vrndavana Conservation Project runs a Trees For Life program in Vraja. The program helps local farmers set up nurseries specializing in fruit trees, for the benefit of their village and local farms. The nurseries include many indigenous species. For a very modest outlay, about 10,000 rupees ($250) per site, plus backup assistance from trained staff, the nurseries not only provide meaningful employment and boost local economy, but also make available trees that could not otherwise be obtained.

In the town of Vrndavana, WWF-India runs the Vrindavan Conservation Project, which includes several nurseries, numerous community projects, and a comprehensive education program in the town's thirty-five schools. Friends of Vrindavan runs a rapidly expanding street-cleaning program, which employs thirty cleaners who patrol several quarters of the town, and is developing recycling programs. Lately the Vrndavana ISKCON temple has joined with Friends of Vrindavan in cleaning up the neighborhood around the temple and helping solve the serious sanitation problems ISKCON's success has helped generate.

Apart from helping run Friends of Vrindavan, ISKCON devotees have set up the Vrinda Trust for the protection of Vrinda Kunj, a sacred grove, and now run a well-stocked nursery of indigenous trees and plants in Vrndavana. But the real work to save Vrndavana's environment has hardly begun.

Pilgrims to Vraja do not need to encounter a land ravaged by drought and deforestation; their pilgrimage can be an opportunity to witness nature protected as an integral part of Krsna devotion. Krsna cared for the forest He swallowed fire to protect it. We also must be prepared to swallow pollution and abuse of nature to save from destruction His groves and the whole ecology of Vraja.

Ranchor Dasa (Ranchor Prime) studied architecture and art before becoming a student and then a teacher of Krsna consciousness, in 1970. He now works as a freelance writer and broadcaster, and as adviser on religion and conservation to WWF and to the Alliance on Religions and Conservation, in Britain and India. He has contributed to several books on religion and the environment, most recently Sacred Britain (Piatkus 1997), and is the author of Hinduism and Ecology (Cassell 1992), Wealth of Faiths (WWF 1994), and Ramayana (Collins & Brown 1997). He is co-founder and director of Friends of Vrindavan. He was born in England in 1950 and lives in London with his wife and two children.

The Vrindavan Conservation Project is described in depth in Hinduism and Ecology, by Ranchor Prime, published in the U.K. by Cassell and in India by Motilal Banarsidas in association with WWF.

Join the Yamuna Cycle Expediition

IN THE MAY/JUNE issue of BTG Ranchor Dasa wrote about his experiences on the Yamuna Cycle Expedition. The 1998 expedition will take place October 9-25, to help raise funds for Friends of Vrindavan projects. It is a superb opportunity for an adventure holiday among the Himalayas and in sacred Vrndavana in the company of devotees and like-minded souls, while at the same time benefiting the environment of Vrndavana. Anyone interested in taking part is invited to contact Ranchor Prime, Trustee, Friends of Vrndavana, 10 Grafton Mews, London W1P 5LF, UK. Phone: +44 (0171) 380 749; fax: +44 (0171) 380 0749. E-mail: ranchor@easynet.co.uk. Or write to Friends of Vrindavan (India), Jaya Singh Ghera, Vrindavan 281 121, U.P., India.