Two Auspicious Baths

After pulling ourselves from the grip of the Ganges, we clamber up the sand bluffs. The river glows like molten lead. The noon wind dries us. Languorous from water, wind, and sun, we make our way slowly up the long cart-track toward Belpukur, the family village of Lord Caitanya's mother, Sacidevi. As the train of devotees stretches itself along the rising trail, cows come streaming down it, lots of them, nudged along by village boys carrying switches. The hoofs of the cows raise a cloud of fine powder, as silky as talcum, that coats our bodies from head to foot. Thus we receive our second "auspicious bath" of the day.

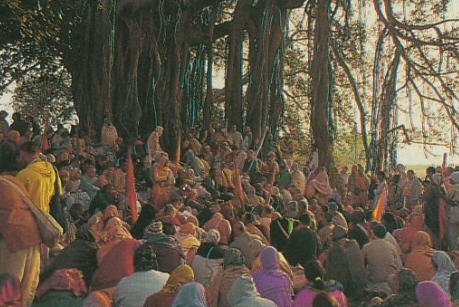

The United Nations of the Spiritual World

For seven days we wander among the fields, villages, and cow sheds deep in the West Bengal countryside, on parikrama. Parikrama means "walking about." We are walking about Sri Navadvipa Dhama, a place of pilgrimage, a tirtha or "ford" for crossing from the material to the spiritual world. This crossing was opened by Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu, who made his advent here 506 years ago. Both before and after the central event, the spiritual realm is manifest here within the material. Parikrama is the process by which the contiguous spiritual geography of Navadvipa is disclosed.

In mundane geography, Navadvipa Dhama encompasses an area thirty-two miles in circumference, centered on Mayapur, a three-mile tract resting on the eastern bank of the Bhagirathi River, a branch of the lower Ganges, directly north of the spot where the Jalangi empties into it. This is about sixty miles north of Calcutta as the crow flies.

On the first day out, our parikrama party holds 800 devotees from 46 different countries. India is represented by 230; Russia, 75; Germany, 60; United States, 50; Poland, 45; Australia, 35; Sweden, Belgium, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom each sends 25; Italy, Hungary, and Yugoslavia, 15 each. Those delegating between six and ten: Spain, France, Peru, Brazil, Denmark, Ukraine, Latvia, Austria, Singapore, Argentina, Bulgaria, Lithuania, South Africa, New Zealand, and Japan. Those with five or less: Fiji, Nepal, Bahrain, Norway, Croatia, Ecuador, Malaysia, Canada, Mauritius, Bangladesh, Slovania, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, Costa Rica, Indonesia, Hong Kong, the Philippines, and Santo Domingo.

Each day our numbers increase. By the seventh and final day our ranks have swollen by 300 more. But there is no documentation to say where they come from.

Thud-Thud-Thud

My first night on parikrama I bed down in an alcove within the sprawling tent complex set up for us. Fluorescent tubes glow its length and breadth. I try to fall asleep, but fairly close by an indefatigable little engine puts out a staccato thudding, an endless plosive stutter. For a long time I listen to that sound. The sudden silence, when it stops, awakens me. All lights are out, the engine driving the generator mute at last.

In the morning dark, I bathe under a portable water tower erected in a nearby field; I am hammered by the same stuttering beat. Crouched in the trampled grass a little engine sucks my bath water up from the lake.

I come to hear that sound everywhere. It is the sound of a two-stroke, three-horsepower diesel engine. Every night a clutch of them chug away about our camps bringing light, water, and amplification. "It is the engine of India," Prthu says.

As we pass through kingdoms of rice fields, the engines hang long strands of sound-beads in the rural silence. The machines hide within straw huts that punctuate the fields, banging tirelessly away. From the side of each hut a wide pipe pours tube-well water into the fields.

We clamber aboard wide-beamed wooden boats fifty feet long to ply up the Ganges. The boatmen crank the engines. Belches of black diesel smoke herald the beginning of the familiar thudding that will escort our flotilla for two hours on the wide waters.

The Cows Look Up

In all the villages we file through it is clear that kine are kin venerable family members who intimately share the courtyards with their human relations. These cherished cows don't eat off the ground like beasts. A kindly consideration provides them with pottery bowls, maybe four feet around, set in earthen pillars three feet high. As our party moves through the villages chanting, the humans line the paths to greet us, while behind them in the cow-crowded courtyards the cows look up from their bowls to acknowledge us with slow bovine stares before attending to their meals again.

Of Soul and Soles

On parikrama the ground underfoot assumes immense importance, because you're supposed to go shoeless. A Western tenderfoot, I start out in my shoes, but take them off the second day after we receive an admonishing lecture by Lokanath Swami, who promises "blisters become bliss." Others repeat the bodybuilder's slogan "No pain, no gain." Nevertheless, I keep my shoes handy in my shoulder bag, just in case.

I noticed the difference right away: barefoot I am definitely more here, in solid contact with the sacred soil. Grounded, or as they say in India, "earthed." However, now my vision perpetually scans the terrain immediately before my delicate feet, and much scenery flows by unseen. The cow paths and cart tracks deep in the country are wonderful: cool, soft powdery earth. Even the brick roads through some larger villages are not bad. But I grow to hate the "government roads" whose dead surfaces abrade the soles and are sown like minefields with sharp tiny stones. I sometimes go shod against the unforgiving asphalt. Is this, too, the holy ground? The question receives some discussion.

As we pick our way barefoot over a rough section, Jayapataka Maharaja tells me, "Kavicandra Swami said he read if you wear your shoes you lose twenty-five percent of the benefit. Hey, only twenty-five percent! That's not so much! Makes you reconsider about the shoes!"

In spite of my caution, my feet at the end have taken their punishment: blistered, pierced, cut, and bruised not just from walking ten vulnerable kilometers a day, but also from incautious dancing and leaping about on unyielding tile or cement. However: the bliss of the soul overcomes the pain of the soles.

The Owls at Mamgachi

Awash in the strong scent of tulasi plants, I am sitting under an ancient bakul tree in a temple courtyard in Mamgachi. I can see the graceful Deity Madana Gopala, once worshiped by Lord Caitanya's associate Vasudeva Datta. The priest who has taken care of Madana Gopala for fifty-four years, man and boy, stands white-haired and stooped on the temple plinth and addresses us. His name is Jagat Bandhu Dasa Brahmacari. The bakul tree is very old and sacred, he tells us; its enormous trunk is hollow; as a child he used to climb down inside it. In the branches of the tree dwell two white owls, emissaries of Laksmi Devi, the goddess of fortune and consort of Visnu. Formerly, the two owls used to appear every evening at the time of arati, when the priest would ring the bell and circle the five-flamed ghee lamp before Madana Gopala and dusk would gather in the branches of the bakul tree. And there the owls would be, watching large, pale, auspicious. But nowadays, the priest says, you don't see them. They appear only very, very rarely.

The Trolley

In the middle of the procession rolls the loudspeaker trolley. A "trolley" in Bengali denotes a certain ubiquitous carrier for goods a man-powered three-wheeled cycle with a flat wooden bed, about five feet long and three wide, set between the rear wheels. The driver of the trolley in our procession never rides; he just pushes. A bamboo mast, about five feet high, is lashed to the seat support; mounted fore and aft are two powerful loudspeakers. Tied above them is the receiver for the cordless microphone, its silver antenna jutting out like a gaff. Two hefty truck batteries and an amplifier ride the flat bed. Also: assorted shoulder bags and backpacks, canteens and bottles of Bisleri water, and the occasional footsore child, who runs the risk, however, of inner-ear damage.

India has embraced sound amplification with unbridled enthusiasm. To Western ears, the whole country seems to have its volume set too high. Mobile and stationary loudspeakers seek you out everywhere. Prthu expounds to me on the theory that in India, Loudness is Truth. The holy name is sweet, but we do keep our distance from the sound trolley.

The other part of the system, the cordless mike, is an unmitigated boon. In procession, the lead Hare Krsna chanter can move at will up and down the line, the percussion section sticking to him like bodyguards around a head of state. When we stop at various holy places, the trolley can sit even at a distance when walls, steps, or slopes block passage, and everyone can hear the preachers and storytellers, who are able to pass the mike around conveniently among themselves.

Best of all, at our stops the cordless mike gives unprecedented freedom to the kirtana leader. With the broadcasting trolley docked alongside the kirtana hall or temple yard, the untethered lead singer is free to plunge into the action on the floor, to spin around, to race back and forth, even to roll on the ground, and thus unbound by cordage to draw energy from the dancing troupe, while the invisible etheric umbilicus carries his mounting enthusiasm to the trolley, which delivers it to the happy crowd.

The Prabhupada-Bearer

At the head of our procession, just behind the banner stretched between two poles, comes Srila Prabhupada in deity form. He's carried each day by Parama Gati Swami, a tall and graceful Brazilian who leads our temple in Paris. Parama Gati Swami has gotten in shape for this service, walking for days before in bare feet to toughen up his soles. As Prabhupada's bearer, he can't break stride or hop around like the rest of us to avoid rough terrain.

Robed in saffron, garlanded with marigolds, Srila Prabhupada rides between gold cushions upon a golden throne. Parama Gati Swami grasps the heavy vyasasana by its sides and bottom, bearing it straight out in front of his solar plexus. To insure a smooth ride, Prabhupada has to be held slightly away from the carrier's body. Every evening Parama Gati Swami has to have his arms and shoulders massaged for a few hours to work the cramps out.

State of the Art

Pennants flying, our pilgrim-laden boat beats up the Ganges and disturbs a huge flock of ducks. A dense cloud of birds bursts into the sky, each tiny dark laboring form precisely etched on pulsing blue. Awestruck, we watch the flock wheel about, drop over the water, rise up, wheel about again, and again, and again in a spectacular display of precision aerial acrobatics. As it slides past shifting vistas of earth and water and air, the racing bird-cloud continually alters shape while all the sharp-edged bird-forms in unison switch aspect from front to side to back. The display reminds me strongly of something. What? Ah! High-powered computer graphics!

We are walking a high dike-road; rice paddies stretch in both directions as far as the eye can see. Ponds for breeding small fish border the road twenty feet below. Suddenly, a large bird, stiletto-beaked, darts athwart us and hovers at eye level just beyond the embankment. I stop and gawk at this kingfisher the size of him! hanging like a hummingbird. Parked in sheer space, the bird peers down intently at the water below. Suddenly it become a falling needle-nosed dart that slips beneath the surface as smooth as grease; a moment later it regains the air in a blue-and-white flurry of feather and froth, a sliver of silver disappearing into its beak. I have looked with awe on stealth fighters and jump-jets, but that was before the demonstration of this hunter's aeronautics.

Excess at Narasimha Palli

It is my first day on parikrama, and when we arrive at Narasimha Palli our final destination I have a headache. I want to be someplace quiet, and dark. I want to be by myself. But I am quite surrounded; the whole village has turned out to sell or watch. The kirtana hall a roofed, open-sided terrazzo stage in front of a small domed temple is crammed with a melee of devotees, who are spilling from the flanks and plunging in again. The sound trolley, drawn up alongside,  demonstrates its potency to the wondering villagers. I crawl into a shady spot in a twin hall (meant for eating) adjacent the kirtana hall. There the uproar is getting wilder and wilder. I see arms flailing about, and the maelstrom in the middle of the press move up and down the hall. Amazingly, I see feet in the air. A roar goes up. I see a well-known sannyasi, of considerable heft, borne up over the devotees' heads. I disapprove. Each crash of drum and cymbal fires a squib of pain in my head. I am wondering where I can escape to, when a muscular, sweat-soaked figure emerges from the mob and lopes half-crouched toward me. It is Ayodhyapati Dasa, a former football player from Memphis, Tennessee, just the sort of fellow who made my life miserable in high school. He seizes my arm in a hard, meaty grip and pulls. I shake my head no, and he pulls harder. I am on my feet and a second later in the middle of the hubbub, buffeted violently on all sides. Ayodhyapati puts his face two inches before mine and screams like a Marine Corps drill instructor at the top of his lungs. He is screaming: "Hare Krsna! Hare Krsna! Krsna Krsna! Hare Hare!"

demonstrates its potency to the wondering villagers. I crawl into a shady spot in a twin hall (meant for eating) adjacent the kirtana hall. There the uproar is getting wilder and wilder. I see arms flailing about, and the maelstrom in the middle of the press move up and down the hall. Amazingly, I see feet in the air. A roar goes up. I see a well-known sannyasi, of considerable heft, borne up over the devotees' heads. I disapprove. Each crash of drum and cymbal fires a squib of pain in my head. I am wondering where I can escape to, when a muscular, sweat-soaked figure emerges from the mob and lopes half-crouched toward me. It is Ayodhyapati Dasa, a former football player from Memphis, Tennessee, just the sort of fellow who made my life miserable in high school. He seizes my arm in a hard, meaty grip and pulls. I shake my head no, and he pulls harder. I am on my feet and a second later in the middle of the hubbub, buffeted violently on all sides. Ayodhyapati puts his face two inches before mine and screams like a Marine Corps drill instructor at the top of his lungs. He is screaming: "Hare Krsna! Hare Krsna! Krsna Krsna! Hare Hare!"

I scream right back. He grins and shoves the microphone into my hand. The drums and cymbals crash. Jolts of energy surge into me from the press of buffeting bodies. The world starts spinning.

Fifteen minutes later, soaking wet, banged up about the ribs, I worm out of the line of scrimmage and fall panting on the sidelines, wondering what came over me. As I try to recover by breath, I feel that meaty grip biting on my arm again. I offer no resistance. He pulls me to a tiny side-door of the temple. "Special mercy," he points out. A devotee is stretched flat into the temple sanctum, his hands grasping the feet of the ancient black image of Narasimhadeva. The devotee gets up, and I stretch into the cool, sweet-scented darkness and hold the feet of the ferocious half-man, half-lion incarnation of Krsna, who once stopped at this place a very long time ago.

Satisfied, the sankirtana drill instructor, coach, instigator, and rabble-rouser hauls me back into the kirtana, where I am good for the course. Later, as we prepare to bathe in the lake, I thank Ayodhyapati. He is limping from a pulled tendon; his forearms bear gashes from the edges of the wide brass cymbals called "whompers." A few scrapes decorate his forehead. "A little rough," I comment. But my headache is quite gone.

As we sit the following morning in a shady grove for breakfast, Sivarama Swami delivers an announcement. He says that the kirtana at Narasimha Palli was somewhat excessive. Of course, you can do anything in ecstasy, but still, he says, we don't see that Lord Caitanya's associates ever picked devotees up and carried them around while others grabbed their feet. (Some of us are looking down abashed.) Sivarama continues: We should keep the holy name in the center. We should take care not to concoct anything and not to get rowdy.

He is right, of course, and after that our kirtanas are never so outre. Even so, I crave them. Narasimha Palli has made me an addict. And Ayodhyapati, of course, still goads us on somewhat subversively, I think.

Digestion

We sail past a sandbar in the Ganges occupied by a party of large, satiated vultures standing at their ease about the remains of some washed-up carrion. Having dined, they are peaceful, satisfied, dignified reminding me of nothing so much as a convocation of pious, prosperous burghers after a memorial banquet.

The Bats of Lord Siva

We gather first in the village square before the empty temple, a small, pretty structure with a fresh pale-yellow wash on its plastered walls and a newly thatched roof. (I learn later that the renovations were paid for by the Bhaktivedanta Swami Charity Trust, established by Srila Prabhupada to restore pilgrimage sites.) Sitting before the temple, we hear about the unusual deity who takes up residence here only twelve days in the year; the rest of the time he reposes under the waters of a nearby lake. He is called Hamsa-vahana Mahadeva, Lord Siva Who Rides A Swan.

Here is the story: Once Suta Gosvami, the famous reciter of Srimad-Bhagavatam at Naimisaranya forest five millennia ago, came to this island in Navadvipa and, endowed with foresight, narrated the future pastimes of Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu. Eager to hear Suta's discourse, Lord Siva mounted his vahana, or carrier, the bull Nandi, and left his abode. Nandi was slow, and Lord Siva became increasingly impatient. Stopping at the abode of Lord Brahma, Siva swapped his bull for Brahma's much swifter swan-carrier, and on that he swooped down onto Navadvipa in time to eagerly drink with his ears the nectar of Lord Caitanya's pastimes.

The Hamsa-vahana deity memorializes Lord Siva's unusual appearance on Brahma's swan, impelled by his ecstatic attraction to Lord Caitanya. The worshipers of Hamsa-vahana say that the deity is always extremely hot, so they must keep him continuously covered with water, like the core of a nuclear reactor. That's why he stays submerged in a lake. On the twelve days in April when Hamsa-vahana comes out to be viewed in the temple, water is poured over him nonstop, around the clock. Otherwise he would heat up and start smoking. All day and all night long queues of people waiting to bathe Hamsa-vahana stretch through the village streets.

Popular opinion holds that Hamsa-vahana is hot from anger (as Siva exemplifies destructive rage), but the truth is that the heat arises from Lord Siva's intense love for Lord Caitanya.

After hearing about Hamsa-vahana, we make our way out of the shady village, chanting loudly. A dirt cart-track takes us through dazzling rice fields toward a bosky tree line, ballooned out by the form of a massive banyan. These trees drink the waters of the lake in which Hamsa-vahana lies submerged.

As we close in on the great banyan, the sky over us erupts with the screeching fluttering forms of monstrous bats, five feet from wingtip to wingtip. These are the fruit bats of the Old World tropics, known aptly as "flying foxes." There are scores of them. Jinking and gyrating madly, they careen about the banyan, and their shrill cries of alarm usher us into the shade of the banyan's soaring vault.

The mammoth trunk is a thick braid of interwoven risers, fused into a U. It perches on the high edge of a slope, crosshatched with knobby roots, that drops away to the lake shore. The entire amphitheater is covered by a vast umbrella of leaf, the ribbings of heavy branches arching far out over the waters. From the overhead vaulting hang multiple ropy descenders, arboreal tails, their tips finely tasseled with roots-to-be, eager for earth.

After working through an obstacle course of living wood, I gain the trunk and sit on a fat root at the mouth of the U, which faces the lake. I peer in. The interior is about two feet across at the opening and reaches back about ten feet, widening out by another foot. Twelve feet up, the sides converge to make a roof. The interior wall, a weave of semi-fused tube-shaped slick-skinned risers, looks uncannily like the extraterrestrial organic structures depicted in Hollywood science fiction films.

The enclosure has been floored with mud, finished with a smooth, dun-colored plaster of cow dung. There is even a step. It is an exquisite bhajana kutir, a sitting place for meditation for a sage with matted locks, a lookout providing a beautiful view of the shaded slope and shore and the hyacinth-covered waters of the lake itself. Most of all, the banyan cave is a place of darsana, of viewing the deity, for in a direct line of sight from the entrance, about fifteen feet out into the plant-choked lake, stands a patch of clear water, in the middle of which rise out the struts of a sunken bamboo frame. Just here, on the lake bottom, coolly reposes Hamsa-vahana Mahadeva.

When Hamsa-vahana comes out of the lake, Subhaga Maharaja says, he is placed in the tree cave and worshiped before being carried to the thatched temple in the village. We set the deity of Srila Prabhupada, seated on his golden vyasasana, within the tree-kutir. First I bend inside to brush out a few dead leaves and curls of dried snakeskin. I get a closer look into the interior. Against the wall hang arrases of well-knit spider webs, the X of a large black spider in the center of each one. The bellies of the spiders are marked horizontally with three parallel white lines the forehead ornament of Lord Siva.

I am asked to addressed the assembly. Overhead the leather-winged foxbats still squeak and gibber as they pivot about the treetop. Looking down at the bamboo slats jutting out of the water, I appeal to Hamsa-vahana Mahadeva to help us distribute Lord Caitanya's mercy in this Kali-yuga, when so many people are ruled by the dangerous and destructive forces of the mode of darkness that Lord Siva himself controls. As the foremost devotee of Krsna, Lord Siva should bestow his mercy to those people plagued by intoxication, insanity, rage, and despair so that they can receive Lord Caitanya's gift of love of God.

Finally we leave the shelter of the banyan tree and again traverse the open fields. Five minutes later we halt in a high pasture, grass grazed to the nub, next to a mango grove. This is the place Suta Goswami recited the pastimes of Caitanya; this field is identical with Naimisaranya, in northwest India, where Suta spoke Srimad-Bhagavatam. Naimisaranya is regarded as the hub of the universe, so any sacrifice performed here redounds to the benefit of all people. Mindful of this, to save all souls, we sit and chant a round of the Hare Krsna mantra on our beads, and then stand and chant Hare Krsna congregationally. The kirtana is mellow and sweet. In the distance I see the flock of bats streaming away from the banyan tree. I watch them wandering over the brightly lit fields, their formation scattered and splayed. Idly, I wonder if they are disoriented by all the light, for it is now well into morning. I return my attention to the kirtana. Suddenly they are massed directly over our heads, fairly low, wheeling about in a tight spirals, their squeaks audible through our chanting. And then the sky is empty.

The Elders

I hear that a number of young devotees profess astonishment to see us old folk all around the half-century mark frolicking in kirtana like kids, forgetful of our dignity and decorum. We do let ourselves go. Afterwards, we sit around complaining to one another about our backs, our hip joints, our ankles, our arches. We vow we won't go overboard like this again; we remind ourselves that we don't have those elastic, quick-mending bodies of youth; but the next day we throw caution and common sense to the wind and whoop it up carelessly, in defiance of gravity.

In his evening years the poet W. B. Yeats wrote, some thought excessively, on carnal themes. "You think it horrible," he addressed these critics, "that lust and rage/ Should dance attention on my old age." He answered them with a rhetorical question: "What else have I to spur me into song?"

Well, here is something else. Here is our singing and dancing school, where aging men clap and sing, disdaining their bones and their dignity, no lust nor rage spurring them into song.

The Real Dirt

"Whoever rolls in the dirt of Surabhi Kunja, chanting the names of Lord Caitanya and Nityananda, receives the special mercy of Nityananda," our guide announces, consulting his guidebook. I file into the entranceway of Surabhi Kunja with the first group to look for a good place to roll in the dirt. It's not easy. Right now, Surabhi Kunja is a construction site, full of stacks of bricks, cement mix, and iron re-bars. Finally, someone discovers a patch of nice sand, and we throw ourselves down into it, rolling and chanting.

Shortly, Jayapataka Maharaja arrives. "Hey!" he exclaims. "This is construction sand! It was brought in from outside! Over here! Look! Here is the real dirt!" I dash over. Sure enough, there is a wide swatch of dark, crumbly earth. It looks good. We fling ourselves down and start rolling.

Subala Vesa

In a field outside a village the cows have been frightened by the crowd of passing pilgrims. Herders chase two mothers and their calves through the rice stubble, trying to get them to cross the road. At the edge the cows balk and bellow, eyes rolling and bulging, and bolt back through their herders. Our group stand well clear until the two cows finally trot swiftly up the road. A cowherd boy picks up the littlest calf, hugging it tightly to his chest, and walks off after its mother.

"Subala vesa," Bhurijana says to me. "You know that story?"

"No."

This is the story he told me; it is about Radha and Krsna.

Srimati Radharani is the embodiment of the internal pleasure potency of Sri Krsna, the Supreme Personality of Godhead. He is the supreme male; she, the supreme female; and the play of their ever-growing love affair is the most secret mystery enacted at the fountainhead of reality. Radha eternally belongs to Krsna, and Krsna to Her, but for the sake of increasing love, the couple forget themselves in dramatic arrangements, by which Srimati Radharani's relation with Krsna is illicit, and scandalous. Defiers of convention, flaunters of morality, the lovers are kept apart by committees of vigilant elders. In anguish, they long for each other and, with their confidantes, obsessively conspire to meet secretly in the Vrndavana forests.

Their success breeds tightened security, and Radha is virtually a prisoner in her own house. Yearning for Krsna, all day long she goes about her duties under the sharp eye of Jatila, her mother-in-law. Others track Krsna's movements. On the day in question, however, a close friend of Krsna's named Subala goes toward the house of Radha's in-laws, with whom she lives. He has a calf with him. At the right spot, Subala gives a twist to the calf's tail; it races off, and as planned charges straight into the courtyard of Radha's family, Subala coming in hot pursuit. Jatila is instantly alert. Warning bells go off.

"What are you doing here?" Jatila demands of the panting Subala after stopping him just past the gate. "You're great buddies with that juvenile delinquent Krsna. The two of you are up to something! I know it! Get out of here!'

"No, no, no," Subala protests. "Mother, you've got it all wrong. I'm just trying to get my calf back, that's all." He smiled charmingly. "And Mother, I have to agree with you about Krsna. I'm finished with him. We had a fight this morning, and I've seen the light. You won't see me hanging out with him anymore, getting into trouble. Now, I'm just trying to do my duty. Please, let me get my calf."

Jatila is persuaded, and she lets Subala go find his calf.

He finds Radharani, and swiftly he gives her his clothes to put on. Subala and Radha could be twins, so alike are their features, so when she is dressed in Subala's cow-herding clothes, she is a dead ringer. Then she wraps her arms about the calf and raises it up. Her breasts are completely hidden.

Giddy with the thought of meeting Krsna, Radharani walks away from her house, directly under the piercing gaze of Jatila, who only sees Subala carrying his calf out. He looks back at Jatila, and with a smile nods in farewell.

That's how Radha came to be dressed in subala-vesa, Subala's clothes. This pastime is still celebrated in Vrndavana temples. If you go on the right day, you'll see the Deity of Srimati Radharani dressed up in the outfit of a cowherd boy and holding a calf to her chest. Because she's dressed in a man's dhoti, it's one of the few times you can see her feet, usually hidden by her skirt or sari.

Tamal Krishna Goswami Suffers A Defeat

After a four-hour march, we are gathered at our final stopping place, in a great hall before the Deities at the yoga-pitha, the birthsite of Lord Caitanya. Devotees have been coming to the microphone on the stage and sharing with the crowd their "parikrama realizations." The other devotees are both instructed and entertained by these presentations, which have gone far past the scheduled time. We are supposed to take breakfast here and arrive back at our temple in time for the noon arati. We won't make it. As people speak, Tamal Krishna Goswami, sotto voce, gathers support among the leaders onstage for a proposal to forgo breakfast in order to return in time for the noon arati: if we are late, the Deities will not be on view, and our final kirtana will suffer.

Satisfied that he has support, Tamal Krishna Goswami puts it to the crowd. He slants the presentation, making his preference clear. We should skip breakfast and be back in time for a grand-finale kirtana. What is eating compared to ecstatic chanting?

"How many want to skip breakfast and leave right away to we can have a huge kirtana?" Strangely, only a few hands go up.

"How many want to honor breakfast prasadam now, and take our chances on getting back?" The hall explodes with cheers and waving arms.

Moral: the sankirtana army, like all armies, moves on its stomach.

Receptions

Devotees Kirtan And Dance in Yoga-pitha

Villagers line the roadside to see us passing by. Sometimes we see them come running across the fields. They press their palms together in respect and, lifting their arms, shout, "Gaura haribol! Gaura haribol!" Sometimes a man will prostrate himself in the road and try to touch the passing pilgrims' feet. Often villagers will spill buckets of water in our pathway as a sign of respect, and then smear their bodies with the water after everyone has passed through. Many times we are received by women with a chorus of shrill ululations, sounding something like the rising and falling trill of cicadas. It is an auspicious sound, like that of a conch shell, and goes by the name of ulu-dhvani.

On the last stretch of our journey, on the road between the yoga-pitha and our own temple, a woman stands, unexpectedly, in the exact center of the highway, facing our advancing column. She waits for us motionlessly, her eyes downcast as we advance toward her. A steel bucket, brimming with water, sits by her feet. A few yards in front of her, we comes to a halt; she stands directly before Srila Prabhupada in Parama Gati Swami's hands. She is a strikingly lovely young woman. She has freshly bathed and is dressed with care in clean, new garments. The white Vaisnava tilaka mark and the large red bindi dot on her forehead, the bright vermilion anointing the part in her shining hair have all been applied with precision. She keeps her eyes shyly downcast. As the half-mile-long column comes gradually to a stop behind us, we stand there as if mesmerized by her intensity of purpose, her shyness, her perfection of dress.

She tips the bucket forward, and the clear water washes toward us, flowing around Parama Gati Swami's feet. She raises a white conch shell to her lips, and three husky, drawn-out notes vibrate the air. She lowers the conch. Then her mouth opens to an O, the tip of her pink tongue oscillates rapidly from side to side, and three long, trilling ululations, rising and falling, fill the air. When the shrill sound fades, she slowly offers obeisances, her forehead on the wet tarmac, and then she steps aside.

The column moves forward.

Mantras of Sacrifice

We turn from the road and approach the great gate to our burgeoning Mayapur City. A reception party has come out. Two elephants stand swaying side to side. Greeters move among the returning devotees heaping garlands of marigolds on them and plastering their foreheads with sandalwood paste. Priests come forward bearing a golden "auspicious pot" of sacrifice on a tray covered with banana leaves; they are surrounded by gurukula boys, who chant the beautiful Purusa-sukta mantras from the Rg Veda.

Led by the elephants, we proceed slowly toward the temple. In front of me ring out the mantras of the ancient Vedic yajna, or sacrifice, the primary dispensation for a time now long past. From behind sounds the driving chorus of Hare Krsna, the mantra of the sankirtana-yajna, the dispensation for the present age. The eternal sounds of the two sacrifices, old and new, mingle and swirl about one another like the waters of the Yamuna and the Ganges in confluence. The mantras of sacrifice sweep us into the temple, where Sri Sri Radha-Madhava are receiving arati.

Saffron Feet

The sound trolley has been drawn up inside the temple, and the microphone moves in the eye of the storm all around the vast hall. The best chanters of the parikrama Krpamaya, Mahamantra, Indradyumna Swami are pushing the outer limits of enthusiasm, and the dancing hosts sway and sashay up and down the hall, join to race in snapping, human chains, link arms shoulder to shoulder and describe counter-rotating circles within circles, form up in tight opposing ranks that close in on each other and recoil like shock troops in close combat. The floor has become heaped with the litter of marigolds from our garlands, and the constant pounding of dancing feet has stirred and pounded them into a mash. The marble turns slick, the hall redolent with the tang of the crushed flowers.

The feet of all the dancers have been dyed saffron up to the ankles by the marigold juice. After two hours I drop to the wayside, hors de combat, to recover in the lee of a pillar. The chanting roars on without me. I look at my feet. The stain is well worked in; the scrape of an experimental fingernail across the skin has no effect.

It will take three days for the saffron to disappear.

Ravindra Svarupa Dasa is ISKCON's Governing Body Commissioner for the U.S. mid-Atlantic region. He lives at the Philadelphia temple, where he joined ISKCON in 1971. He holds a Ph.D. in religion from Temple University.