“I worship that transcendental seat, known as Svetadvipa . . . where every word is a song, every gait is a dance, and the flute is the favorite attendant.” (Sri Brahma-samhita 5.56)

What is th e purpose of art? In art college I learned that it is a way to express something about oneself, something original. Fair comments, but what about the point of it all? What should be the reason for a work of art, a dance, or a piece of music? For many, it is the creation itself, or even the desire for the fame that comes with making something never created before.

I left art college with this question burning in my heart, having been introduced to Krishna consciousness by a friend at school. I read Prabhupada’s books, but spent more time absorbing myself in the beauty of the artwork depicting the pastimes of God in all of their variety. Almost immediately I started to work on producing detailed illustrations of Lord Krishna and His Vrindavana pastimes. I discarded many of those over the years, but they served as foundations for later ideas.

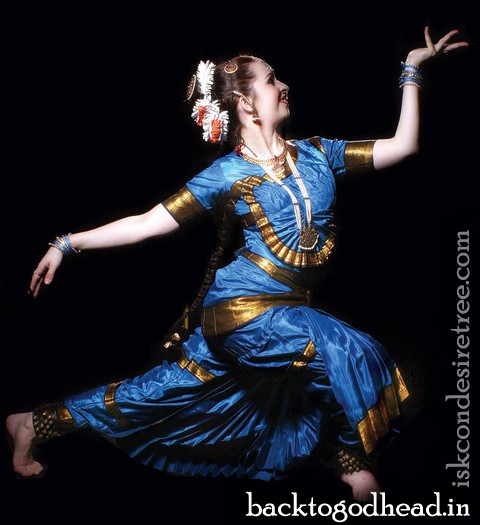

I stayed in the ashram for some time and then left for India, where the beauty of classical dance and music filled my senses. Sometimes I heard strains of the sweetest music coming from someone’s house or garden, and I would often stand in one place until I’d memorized the melody. Other times I would see dancers large black eyes, faces alive with expression, feet both powerful and elegant with the sound of dozens of tiny bells. I decided I’d make myself an artist for God, for Krishna, and this would be my meaning, the reason for being an artist.

Little did I realize then to what depth the ancient sages of India had researched music, dance, and art. Traditional India has a wonderful way of discovering the spiritual essence of any aspect of our human experience and creating powerful art as a consequence. An ancient story tells of the sage Bharata, author of Natya Shastra, India’s foremost treatise on the performing arts. Brahma, engineer of the universe, gave the Natya Shastra to Bharata, who along with groups of Gandharvas and Apsaras (celestial musicians and dancers) performed before Lord Shiva. On seeing this astonishing performance, Lord Shiva remembered His own majestic dance, the tandava-nrtya, and he and his consort, Parvati, taught Bharata the art of dance, which was later brought to earth.

Dance

Spiritual people sometimes see dance as narcissistic. Is it possible to dance for the Lord without slipping into the desire for fame and adulation? I believe so, but it must be done as sadhana, or spiritual practice.

In 1993 I started Bharata Natyam dance training with Guru Prakash Yadagudde, resident teacher at the Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, an organization with centers in India and elsewhere for the promotion of the Indian cultural arts. Alongside this, I studied Karnatic (South Indian) music to better understand how dance and music are woven together. I discovered I had an aptitude for singing, something I was only vaguely aware of before. Very soon I had taken up singing at diploma level and was even teaching.

The training for Bharata Natyam is arduous and requires commitment for success, but I became captivated by its spiritual depth and the exquisite beauty of the movements. In his book Bharata Natyam, Sunil Kothari describes the dance beautifully: “It is one of the most subtle, sophisticated and graceful styles of danceart in the world. Flowers open in the hands of the dancer, and birds fly off from the tips of the fingers, the body sways, now in pride, now in devotion. . . . Such a dance drama, performed according to the most delicate nuances of a musical piece, or a poem, through the vehicle of one body, is surely unmatched in any art.”

As a devotee of Krishna, I had learned that bhakti is the yoga of action, a way in which to channel one’s occupation into the service of Lord Krishna simply by engaging oneself in a mood of devotion. As a dancer, I discovered this to be true. After the initial austerity of learning to express myself in a way alien to my native culture, I learned to portray the pastimes of Sri Krishna with His characteristic mischief, playfulness, and cleverness. I spent hours in front of a mirror, trying to emulate Krishna and His devotees as naturally as possible.

The famous dancer Rukmini Devi Arundale said, “A truly spiritual artiste is one who also forgets himself and in that self forgetfulness achieves bliss which is called ananda.” It should be added here that self-forgetfulness indicates that the dancer allows herself or himself to become a vessel through which a deity is channelled. Anyone who has seen great dancers will have realized that their fame has come about not because of their physical technique, as there are many technically perfect dancers, but for the way in which their portrayal of divinity can make a two-hour performance seem like two minutes. There is something awesome about a dancer who appears on the stage clad in red and taking on the personality of a fierce goddess, then re-enters as the gentle mother of Lord Rama, Kaushalya. Our emotions follow the transformations, and we become absorbed in thoughts and emotions related to the Lord and His servants.

Music

My journey into music has been one of the most spiritually transformative experiences of my life. Three years ago I started a BM us degree in North Indian/Sikh music with Professor Surinder Singh, head of an organization called Raj Academy, a London-based group focused on the healing aspects of Indian music. Traditional Indian music is based on something called raga, a concept with many layers of meaning. On the most basic level, raga is a musical scale of five to seven ascending and descending swaras, or notes. There are thousands of ragas, many of them having the same swaras. What makes the difference is that each scale is given character and rasa, or flavor, by placing different emphasis on certain notes and relating them to each other in various ways. A raga, then, is an expression of profound emotion in all of its complexity. Ragas can be spiritual or mundane, depending on their musicology, or the way in which they were designed.

I once saw someone who exemplified what it means to devote one’s life to the sadhana of art as devotion. Pandit Ram Narayan is known to many as the sarangi maestro of India. The sarangi is an instrument thought to have been created by Ravana, the ten headed demon of the Ramayana and an expert musician. The word sarangi means “all colors,” indicating that the instrument can capture every emotion, both mundane and spiritual. Panditji explained to the audience that the deity was indeed present in a raga. He then played the raga Sri, the personification of Parvati, consort of Lord Shiva. When Panditji had finished, silence filled the room, the audience initially too stunned to applaud. The presence of the goddess was undeniable.

India’s science of music is almost lost these days, even to Indian musicians, many of whom consider much of what is said in ancient texts to be mythology. One of the most famous musicologists of the Vedic period was Narada, thought by many to be the Narada Muni of Krishna’s pastimes. In his Naradiya Siksa, the sage outlines ragas and their relation to mood, colors, planets, chakras, and other esoteric factors fundamentally connected to sound and its manifestation in the world. In particular, his text is the first to describe what are known as Srutis, or the sounds that exist between the twelve commonly used notes. Ragas are played or sung with high or low emphasis on the Srutis. Although to the average person these minute changes in sound are imperceptible, they are perceived subtly and can alter our moods and feelings. The conscious use of Srutis and the characteristic sliding notes of ragas are what make Indian music obviously different from the music of the West.

Many of our Gaudiya Vaishnava predecessors were expert musicians with extensive knowledge of raga music, poetic meter, and taal, or specific rhythms. Jayadeva Goswami in his Gita Govinda names the raga to accompany each poem and explains its appearance and character. Candidasa, a poet loved by Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu, wrote his Sri Krishna Kirtana in different ragas, as did Govinda Dasa and Vidyapati in their treatises. While our focus should always be on the holy name rather than our expertise in music, I believe we can only gain by having some understanding of the effect of raga music and applying it to our bhajanas and kirtanas.

Art

A dancer engages the body in the service of the Lord, a singer, the ears and voice. For the artist, the eyes are absorbed in the beauty of the form of God, which manifests from the heart and onto the canvas. Hours become moments as Sri Krishna’s form appears His restless eyes, His rain-cloud-blue skin, His curling black hair. A song by Bhaktivinoda Thakura says, “O son of Nanda, let me worship You with the lamplight of my eyes.”

As a spiritual artist, I have created Nataki, a website dedicated to the propagation of spiritual dance, music, and artwork. The word nataki means a woman performer, usually a dancer. In ancient India this would almost always imply a devotional career as a temple performer. I created Nataki because of my deep belief that all healing, all devotion, and all spiritual advancement can be attained through the medium of being an artist. While I’m still a student, I hope that my website will encourage others to realize, as I have, the depth, beauty, and devotion inherently present in Indian traditional art forms. Ancient India has made every possible facet of life into art. Indeed, this is perhaps the most outstanding contribution of the Vedic literature. We all seek a way to engage our senses in something that has absolute meaning for our souls.

Indulekha Devi Dasi, who lives in London, has been a member of the Hare Krishna movement since 1988. She regularly performs as a dancer and is establishing herself as a teacher of Indian dance and music, as well as promoting her artwork. Her website is www.nataki.co.uk.