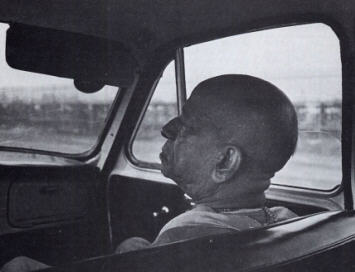

The Departure 1967: The Lower East Side, New York.

Srila Prabhupada leaves his small storefront temple to open a center in the heart of San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district.

The temple at 26 Second Avenue was thriving, but now it was time to break new ground. And the most fertile field was San Francisco's Haight-Ashhurv district, where the cultural revolution that had begun on the Lower East Side was about to explode with a mass migration of searching, frustrated young people.

Kirtanananda, Brahmananda, Acyuta-nanda, Girgamuni, Satsvarupa, Hayagriva, Umapati, Jadurani, Rupanuga, Damodara their lives had all been transformed. Over the months they had transferred the center of their lives to Swamiji, and everything revolved around the daily routine of classes and kirtana and prasadam and coming and going to and from the storefront.

Brahmananda and Gargamuni had given up their apartment several months ago and moved into the storefront. The ceiling of Acyutananda's apartment had caved in one day, just minutes after he had left the room, and he had decided to move to the storefront also. Hayagriva and Umapati had cleaned up their Mott Street place and were using it only for chanting, sleeping, or reading Swamiji's Bhagavatam. Satsvarupa had announced one day that the devotees could use his apartment, just around the corner from the temple, for taking showers, and the next day Raya Rama had moved in, and the others began using the apartment as a temple annex. Jadurani kept making her early-morning treks from the Bronx. (Swamiji had said that he had no objection to her living in the second room of his apartment, but that people would talk.) Even Rupanuga and Damodara, whose backgrounds and tastes were different, were also positively dependent on the daily morning class and the evening class three nights a week and in knowing that Swamiji was always there in his apartment whenever they needed him.

There were, however, some threats to this security. Prabhupada would sometimes say that unless he got permanent residency from the government he would have to leave the country. But he had gone to a lawyer, and after the initial alarm it seemed that Swamiji would stay indefinitely. There was also the threat that he might go to San Francisco. He said he was going, but then sometimes he said he wasn't.

But at least in the morning sessions, as his disciples listened to him speak on Caitanya-caritamrta, these threats were all put out of mind, and the timeless, intimate teachings took up their full attention. Krsna consciousness was a hard struggle, keeping yourself strictly following Swamiji's code against mya "No illicit sex, no intoxication, no gambling, no meat-eating." But it was possible as long as they could hear him singing and reading and speaking from Caitanya-caritmrta. They counted on his presence for their Krsna consciousness. He was the center of their newly spiritualized lives, and he was all they knew of Krsna consciousness. As long as they could keep coming and seeing him, Krsna consciousness was a sure thing as long as he was there.

One of Prabhupada's main concerns was to finish and publish as soon as possible his translation and commentary of Bhagavad-gita, and one day something happened that enabled him to increase his work on the manuscript. Unexpectedly, a boy named Neal arrived. He was a student from Anti-och College on a special work-study program, and he had the school's approval to work one term within the asrama of Swami Bhaktivedanta, which he had heard about through the newspapers. Neal mentioned that he was a good typist, if that could be of any help to the Swami. Prabhupada considered this to be Krsna's blessing. Immediately he rented a dictaphone and began dictating tapes, Hayagriva donated his electric typewriter, and Neal set up his work area in Swamiji's front room and began typing eight hours a day. This inspired Prabhupada and obliged him to produce more. He worked quickly, sometimes day and night, on his Bhagavad-gita As It Is. He had founded ISKCON five months ago, yet in his classes he was still reading the Bhagavad-gita translation of Dr. Radhakrishnan. But when Bhagavad-gita As It Is would be published, he told his disciples, it would be of major importance for the Krsna consciousness movement. At last there would be a bonafide edition of the Gita.

Whatever Swamiji said or did, his disciples wanted to hear about it. Gradually, they had increased their faith and devotion to Swamiji, whom they accepted as God's representative, and they took his actions and words to be absolute. After one of the disciples had been alone with him, the others would gather around to find out every detail of what had happened. It was Krsna consciousness. Jadurani was especially guileless in relating what Swamiji had said or done. One day, Prabhupada had stepped on a tack that Jadurani had dropped on the floor, and although she knew it was a serious offense to her spiritual master, the major importance of the event seemed to be how Prabhupada had displayed his transcendental consciousness. He silently and emotionlessly reached down and pulled the tack from his foot, without so much as a cry. And once, when she was fixing a painting over his head behind the desk, she had accidentally stepped on his sitting mat. "Is that an offense?" she had asked. And Swamiji had replied, "No. For service you could even stand on my head."

Sometimes Brahmananda would say that Swamiji had told him something very intimate about Krsna consciousness in private. But when he would tell what Swamiji had said, someone else would recall reading the same thing in Srimad-Bhagavatam.Prabhupada had said that the spiritual master is present in his instructions and that he had tried to put everything into those three volumes of the Bhagavatam, and the devotees were finding this to be true.

There were no secrets in Swamiji's family of devotees. Everyone knew that Umapati had left for a few days, disappointed with the Swami's severe criticism of the Buddhists, but had come back, and in a heavy, sincere exchange with Prabhupada, he had decided to take to Krsna consciousness again. And everyone knew that Satsvarupa had quit his job and that when he went to tell Swamiji about it, Swamiji had told him he could not quit but should go on earning money for Krsna and donating it to the Society and that this would be his best service. And everyone knew that Swamiji wanted Gargamuni to cut his hair Swamiji called it "Gargamuni's Shakespearean locks" but that he would not do so.

The year ended, and Swamiji was still working on his manuscript of Bhagavad-gita, still lecturing in the mornings from Caitanya-caritamrta and Monday, Wednesday, and Friday evenings from Bhagavad-gita, and still talking of going to San Francisco. Then New Year's Eve came, and the devotees suggested that since this was a holiday when people celebrate, maybe they should hold a Krsna conscious festival.

Rupanuga: So we had a big feast, and a lot of people came, although it wasn't as crowded as the Sunday feasts. We were all taking prasadam, and Swamiji was sitting up on his dais, and he was also taking prasadam. He was demanding that we eat lots of prasadam. And then he was saying,

"Chant! Chant!" So we were eating, chanting Hare Krsna between bites, and was insisting on more and more prasadam. I was amazed. He stayed with us until around eleven o'clock, and then he became drowsy. And the party was over.

Sometimes, during the evening gatherings in his room, Swamiji would ask whether Mukunda was ready on the West Coast. For months, Prabhupada's going to West Coast had been one of a number of alternatives. But then, during the first week of the New Year, a letter arrived from Mukunda: he had rented a storefront in heart of the Haight-Ashbury district, Frederick Street. "We are busy converting into a temple now," he wrote. And Prabhupada announced: "I shall go immediately." Mukunda had told of a "Gathering of Tribes" in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury. Thousands of hippies were migrating from all over the country to the very neighbourhood where Mukunda had rented storefront. It was a youth renaissance much bigger than what was going on in New York City. In a scheme to raise funds for the temple, Mukunda was planning a "Mantra Rock Dance," and famous rock bands were going to appear. And Swami Bhaktivedanta and the chanting of Hare Krishna were to be the center of attraction!

Although in his letter Mukunda had closed a plane ticket, some of Swamiji's followers refused to accept that Swamiji would use it. Those who knew they could not leave New York began to criticize idea of Swamiji's going to San Francisco. They didn't think that people out on West Coast could take care of Swamiji properly. Swamiji appearing with rock musicians? Those people out there didn't seem to have the proper respect. Anyway, there was no suitable temple there. There was no printing press, no back TO godhead magazine. Why should Swamiji leave New York to attend a function like that with strangers in California? How could he leave them behind in New York? Timidly, one or two dissenters indirectly expressed some of these feelings to Prabhupada, almost wishing to admonish him for thinking of leaving them, and even hinting things would not go well, either in San Francisco or New York, if 'he departed. But they found Prabhupada quite confident and determined. He did not belong to New York, he belonged to Krsna, and he has to go wherever Krsna desired him to preach. Prabhupada showed a spirit of complete detachment, eager to travel and expand the chanting of Hare Krsna.

In the last days of the second week of January, final plane reservations were made, and the devotees began packing Swamiji's manuscripts away in trunks. Ranacora, a new devotee recruited from the Tompkins Square Park, had collected enough money for a plane ticket, and the devotees decided that he should accompany Prabhupada as his personal assistant. Prabhupada explained that he would only be gone a few weeks, and that he wanted all the programs to go on in his absence.

He waited in his room while the boys arranged for a car to take him to the airport. The day was gray and cold, and steam hissed in the radiators. He would take only a suitcase mostly clothes and some books. He checked the closet to see that his manuscripts were in order. Kirtanananda would take care of his things in his apartment. He sat down at his desk where, for more than six months, he had sat so many times, working for hours at the typewriter preparing his Bhagavad-gita and Srimad-Bhagavatam, and where he had sat talking to so many guests and followers. But today he would not be talking with friends or typing a manuscript, but waiting a last few minutes alone before his departure.

This was his second winter in New York. He had launched a movement of Krsna consciousness. A few sincere boys and girls had joined. They were already well known on the Lower East Side many notices in the newspapers. And it was only the beginning.

He had left Vrndavana for this. At first he had not been certain whether he would stay in America more than two months. In Butler he had presented his books. But then in New York he had seen how Dr. Mishra had developed things and the Mayavadis had a big building. They were taking money and not even delivering the real message of the Gita. But American people were looking.

It had been a difficult year. His God-brothers hadn't been interested in helping, although this is what their Guru Maharaja, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura, wanted, and what Lord Caitanya wanted. Because Lord Caitanya wanted it, His blessings would come, and it would happen.

This was a nice place. 26 Second Avenue. He had started here. The boys would keep it up. Some of them were donating their salaries. It was a start.

Prabhupada looked at his watch. He put on his tweed winter coat and his hat and shoes, put his right hand in his bead bag, and continued chanting. He walked out of the apartment, down the stairs, and through the courtyard, which was now frozen and still, its trees starkly bare without a single leaf remaining. And he left the storefront behind.

He left, even while Brahmananda, Rupanuga, and Satsvarupa were at their office jobs. There was not even a farewell scene or a farewell address. (To be continued.)