One of the first American young people to take an interest in Prabhupada was Robert Nelson. Although he had grown up in New York City, he was more like a slow, simple country boy with a lumbering, homespun manner. At that time he was about twenty years old and was receiving unemployment checks. Robert (or, as Prabhupada called him, Mr. Nelson) was a loner. He was not part of the growing hippy youth movement, he did not take marijuana or other drugs, nor did he socialize much. He'd had some technical education at Staten Island Community College and had tried his hand at a record manufacturing business, but without much success. He was interested in God and would attend various spiritual meetings around the city. In this way he had wandered several times into Dr. Misra's Yoga Society and had heard lectures. He remembers the night he first saw Srila Prabhupada.

Svamiji [Srila Prabhupada] was sitting cross-legged on a bench. There was a meeting, and Dr. Misra was standing up before a group of people. There were about fifty people coming there, and he talked on "I am consciousness." Dr. Misra talked and then gave Prabhupada a grand introduction with a big smile. "Svamiji is here, "he said. And he swings around and waves his hood for a big introduction. It was beautiful. This was after Dr. Misra spoke for about an hour. Prabhupada didn't speak; he sang a song.

I went up to Prabhupada. He had a big smile and said, "Yes." Then he said that he likes young people to take to Krsna consciousness. He was very serious about it. He wanted all young people. So I thought that was very nice. It made sense. He said the young people are different. When they get older it is like a waste of time. Prabhupada said when he meets someone young it becomes entirely different. So I wanted to help.

We stood there about an hour. Misra had a library in the back, and we looked at certain books Arjuna, Krsna, chariots, and things. And then we walked around. We looked at some of the pictures of svamis on the wall. By that time it was getting very late, and Prabhupada said to come back the next day at ten to his office downstairs.

The next day, Robert Nelson went to Room 307 and knocked on Prabhupada's door. He remembers the Svami inviting him in and handing him a small piece of paper with the Hare Krsna mantra printed on it. "While Swamiji was handing it to me he had this big smile like he was handing me the world." Srila Prabhupada showed Robert three volumes of the Srimad-Bhagavatam, which Robert purchased for $16.50. Robert remembers that the walls of the room were painted "a dark, dismal color." The place was clearly not intended to serve as a living quarters there was no toilet, shower, chair, bed, or telephone.

So we spent the whole day together [Robert Nelson relates]. At one point Prabhupada said, "We are going to take a sleep." So he laid down there by his little desk, and so I said, "I am tired too." So I laid down at the other end of the room and we rested. I just laid on the floor. It was the only place to do it. But he didn't rest that long-an hour and a half I think and then we spent the rest of the day together. He was talking about Lord Caitanya and the Lord's pastimes, and he showed me a small picture of Lord Caitanya, and then he started talking about the disciples of Lord Caitanya, Nityananda, and Advaita. He had a picture of the five of them [Lord Krsna's incarnation as Lord Caitanya, with His four principal associates] and a picture of his spiritual master. It wasn't much of a room, though. You'd really be disappointed if you saw it.

Presents and Presentations

Robert Nelson couldn't give Prabhupada the kind of assistance he needed. Lord Caitanya has stated that a person has at his command four things, of which he should give at least one to the service of God: he can give his whole life; or if he cannot do that, he can give his money; if he cannot give his money, he can give his intelligence; and if he does not have intelligence, he can at least give his words, by telling others about the glories of God. Robert Nelson did not seem able to give his whole life to Krsna consciousness, and as for money, he had very little. His intelligence was also limited, he spoke unimpressively, and he did not have a wide range of friends or contacts with whom to speak. But he was affectionate toward Srila Prabhupada, and out of the eight million people in the city, he was at this time almost the only one who showed personal interest and offered what little help he could.

Robert, with his experience in manufacturing records, had a scheme that he could make a record of Prabhupada singing, so he tried to convince Prabhupada to put out an album of devotional songs. One could put out an album with almost anything on it, he told Prabhupada, and it would make money, or at least break even. An album that costs only thirty-five cents to make could always be put in an assortment and sell for sixty cents, so it would be almost impossible to lose money. Robert thought this was a way he could help make Prabhupada known, and he convinced Prabhupada that it was worth making a presentation to a record manufacturer.

Me and Prabhupada went around to this record company on Forty-sixth Street. We went in there, and I started talking, and the man was all business. He was all business and mean they go together. So me and Prabhupada went in there with the tape, and we tried talking to the man. Prabhupada was talking, but the man said he couldn't put the tape out. I think he listened to the tape, but he wouldn't put it out. So we felt discouraged. Prabhupada was discouraged, but he didn't say much about it. He wanted to have an album put out. It would have been so nice if that man had put out the album.

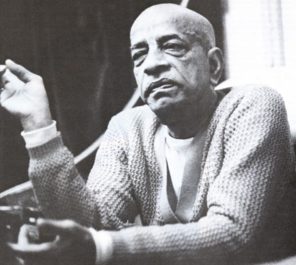

Robert Nelson and Srila Prabhupada made an odd combination. Srila Prabhupada was elderly and dignified and was a deep scholar of the Bhagavatam and the Sanskrit language, whereas Robert was artless in both Eastern and Western culture and inept in worldly ways. They walked together, uptown on various adventures Srila Prabhupada wearing his winter coat (with its collar of imitation fur) along with his Indian dhoti and white pointed shoes, Robert wearing old khaki pants and an old coat. Srila Prabhupada walked with rapid, determined strides, outpacing the lumbering, rambling, heavyset boy who had befriended him.

Robert was supposed to help Srila Prabhupada in making presentations to businessmen and real estate men, but he himself was hardly a slick fellow. He was quite innocent.

Once we went over to this big office building on Forty-second Street, and we went in there. The rent was thousands of dollars for a whole floor. So I was standing there talking to the man, but I didn't understand how all this money would come, because Prabhupada wanted a big place and I didn't know what to tell the man. The man was asking some big price just for the rent. That was between Sixth and Broadway on Forty-second Street. Some place to open Krsna's temple! We went in and up to the second floor and saw the renting agent, and then we left. I think it was $5,000 a month or $10,000. We got to a certain point, and the money was too much. And then we left. When he brought up the prices. I figured we had better not, we had to stop. Previously I had seen a sign, and it was my idea to take Prabhupada there.

Another time Robert took Srila Prabhupada to the Hotel Columbia, at 70 West Forty-sixth Street. The hotel had a suite that Srila Prabhupada looked at for possible use as a temple, but again he found it too expensive.

Sometimes Robert would make purchases for Srila Prabhupada with money from his unemployment checks. One time he bought orange-colored T-shirts. Another time he went to Woolworth's at Fiftieth Street between Sixth and Seventh Avenues and bought frying pans and picture frames for Prabhupada's pictures of Lord Caitanya and his spiritual master.

"One time I wanted to know how to make capati cakes," Robert said, "so Prabhupada says, 'A hundred dollars, please, for the recipe. A hundred dollars, please.' So I went and got some money, but I couldn't get a hundred dollars. But he showed me anyway. He taught me to cook and would always repeat, 'Wash hands, wash hands,' 'You should only eat with your right hand.'

Whoever met Srila Prabhupada was almost always impressed, Robert remembers. "They would start smiling back to him, and sometimes they would say funny things to each other that were nice. Prabhupada's English was very technical always. I mean, he had a big vocabulary. But sometimes people had a little trouble understanding him, and you had to help sometimes."

Robert Nelson's observation that Prabhupada liked young people to take to Krsna consciousness is significant. Srila Prabhupada was already seriously considering that his message would be appreciated especially by the youth of America. In Bengal, Lord Caitanya had started His movement of sankirtana, congregational chanting, when He was fifteen or sixteen years old, and many of His followers were also teenagers. In the Bhagavatam a young boy devotee, Prahlada, preaches to his schoolmates that they should take to spiritual life while very young, because as one grows older he becomes entangled in household life, and then spiritual life becomes impossible. Of course, Srila Prabhupada was not discriminating, or thinking that only people of a certain age group should receive Krsna consciousness. Indeed, it was mostly older people who had so far given him a hearing.

A man by the name of Harvey Cohen, who was then in his thirties, proved an important link with the young people of New York City. A commercial artist who lived on the Lower East Side, Harvey had seen Prabhupada one evening at Dr. Misra's yogastudio, and he began to describe Srila Prabhupada to some of his friends at the Paradox restaurant, at 64 East Seventh Street. It was Dr. Misra who had given Srila Prabhupada shelter uptown, where he had at least survived, but it was through Harvey Cohen and then others from the Paradox that a whole new phase of Prabhupada's life in America began. Young seekers began to be attracted to him. A young friend of Harvey's named Bill Epstein, who was then in his early twenties, says his own coming to see Prabhupada was due to Harvey Cohen and the Paradox restaurant: "Harvey Cohen came to me and said, 'I went to visit Misra, and there's a new svami there, and he's really fantastic!'

The Paradox, a macrobiotic establishment, was a center for spiritual-cultural interests in the 1960s. Run by a man named Richard O'Kane, the Paradox served natural food based on the philosophy of George Osawa and the macrobiotic diet. It was a kind of meeting place reminiscent of Parisian cafes or Greenwich Village in the 1920s. In this storefront, one flight down from the sidewalk, small dining tables were placed around a room which was generally lit by candlelight. There was also a courtyard in the back, where people could sit at tables under trees. The food was inexpensive and well reputed. Tea was served free, as much as you liked. A person could spend the whole day at the Paradox without buying anything, and no one would chase him out.

For some, the people at the Paradox were like a mystical congregation. It was not merely a New York scene, but was frequented by people traveling from Europe and other parts of the world. The people at the Paradox were always interested in teachers from India or the East. The Paradox culture was originally not oriented toward LSD or other drugs, but was centered on internationalism, spiritual inquiry, and the Osawa diet. It gradually turned out, however, that people who had taken LSD were attracted to the restaurant, because of its atmosphere of mind expansion and mystical interest. "Even the mystics have to eat," said James Greene, who was then a thirty-year-old freelance carpenter teaching at Cooper Union and reading his way into Eastern philosophy. He was another who heard about Srila Prabhupada while regularly taking his evening meal at the Paradox in the spring of 1966.

Bill Epstein was an employee at the Paradox, and once he became interested in Prabhupada, he made Prabhupada an ongoing topic of conversation. Quite in contrast to Robert Nelson, Bill Epstein was a dashing, romantic person with long, wavy dark hair and a beard. He was good-looking and effervescent and took upon himself a social role of informing people of the city's spiritual news. It was through Harvey Cohen that he first met Srila Prabhupada.

When Harvey Cohen came down to the Paradox [Bill Epstein relates], at first I couldn't care less. I was involved in macrobiotics and Buddhism, but Harvey was a winning and warm personality, and he seemed interested in this. He said, "Why don 't you come uptown? I would like you to see this. "So I went to one of the lectures on Seventy-second Street. I walked in there, and I could feel a certain presence from the Svami. He had a certain very concentrated intense appearance. He looked pale and kind of weak; I guess he had just come here and he had been through a lot of things. He was sitting there chanting on his beads, which he carried in a little bag. One of Dr. Misra '5 students was talking, and he finally got around to introducing the Svami. He said, "We are the moons to the Svami's sun." He introduced him in that way. The Svami got up and talked. I didn't know what to think about it.

So I went back to the Paradox and said, "Well, Harvey, I went to see the Svami. " He said, "What did you think?" I said, "Well, you know, it is interesting. "At that time the only steps I had taken in regard to Indian teaching was through Rama-krishna, but this was the first time that bhakti religion had come to America.

Then another time Harvey came to the Paradox, and I asked, "How is the Svami living? Where is he getting his money from?"

He said, "I don't know."

I asked, "Does he have food?"

He said, "I don't know if he's got anything up there."

I asked, "Have you gone to see him where he's living?"

He said, "Yes. He lives now on the third floor, in Room 307."

I said, "Well, you know what I think I'm going to do? I'm going to take him some food from here and bring it up there and see f he could use it."

He said, "Yes, that sounds like a good idea. I don't know how he's getting his food."

So I went in the back, and I asked Richard, the manager, "I'm going to take some food to the Svami You don't mind, do you?" He said, "No. Take anything you want. "So I took some brown rice and other stuff and I brought it up there.

I went upstairs and I knocked on the door, and there was no answer. I knocked again, and I saw that the light was on because it had a glass panel and finally he answered. I was really scared, because I had never really accepted any teacher. He said, "Come in! Come in! Sit down." We started talking, and he said to me, "The first thing that people do when they meet is to show each other love. They exchange names; they exchange something to eat." So he gave me a slice of apple, and he showed me the tape recorder he had, which probably Harvey Cohen gave him so he could record his chants. Then he said, "Have you ever chanted?" I said, "No, I haven't chanted before." So he played a chant, and then he spoke to me some more. He said, "You must come back." I said, "Well, or I come back I'll bring you some more food."

Almost all the people going up to see Srila Prabhupada at this time were coming from the Paradox. People taking their dinner in the restaurant would be approached by Bill Epstein or others with the proposal, "Let's go up to the Svami's." Whenever Bill Epstein went he would bring food and sit and chant. Some of the people who went thought that Prabhupada was being too exclusive by saying that the only way to reach God was to sing Hare Krsna. But because most of them were people who were open to experimenting with new things, they began chanting, and then they would like it. Those who had experienced the visit uptown to the Svami talked favorably about it at the restaurant to those who had never gone.

Coming Downtown

Another sympathizer who met Srila Prabhupada through the restaurant was James Greene. Older and more responsible, he had been living for eight years on the same block as the Paradox.

Initially we had gone to attend one of Dr. Misra's lectures [James Greene relates.] It was really Harvey and Bill Epstein who got things going. I remember one meeting at Misra's. Svami was only a presence; he didn't speak. Misra's students seemed more into the bodily aspect of yoga. This seemed to be one of Svamji's complaints.

His room on Seventy-second Street was quite small. He was living in a fairly narrow room. It must have been ten feet by fifteen feet. It had a door on one end, and Svamiji had set himself up along one side, and we were rather closely packed. It may have been no more than eight feet wide, and it was rather dim. He sat on his thin mattress, and then we sat on the floor.

At that time we didn't chant. We would just come, and he would lecture. There was no direction other than the lecture on Bhagavad-gita. I had read a lot of literature, and in my own shy way I was looking for a master, I think. I have no aggression in me or go-getting quality. I was really just a listener, and this seemed right hearing the Bhagavad-gita so I kept coming. It just seemed as if things would grow from there. More and more people began coming. Then it got crowded, and he had to find another place.

Another of the first seekers who came to see Prabhupada uptown was Paul Murray. Eighteen years old, he had just moved to the city, optimistically attracted by what he had read about experimentation with drugs. Paul remembers a clash between the Paradox group and the more conservative, older guests who had been attending Prabhupada's classes. The young men, he says, found "a kind of fussbudgety group of older women on the West Side" listening to Prabhupada's lectures. At that time it was unusual for people to have long hair and beards, and when such people started coming to the West Side to visit Prabhupada, some of the older people were alarmed. "Swami Bhaktivedanta began to pick up another kind of people," one of them says. "He picked them up at the Bowery or some attics. And they came with funny hats and grey blankets around themselves, and they startled me."

We weren't known as hippies then [Paul Murray relates]. But it was strange for the people who had originally been attracted to him. It was difficult for them to relate to this new group. I think most of the teachers from India up to that time had older followers, and sometimes wealthy widows would provide a source of income. But Svamiji changed right away to the younger, poorer group of people.

The next thing that happened was that Bill Epstein and others began talking about how it would be better for the Svami to come downtown to the Lower East Side. Things were really happening down there, and somehow they weren't happening uptown. People downtown really needed him. Downtown was right and it was ripe. There was life down there. There was a lot of energy going around.