Transcendental Commentary on the Issues of the Day

The quality of service in America is at an all-time low, say the media. Now, more than ever, the worn cliche "You just can't get good help nowadays" has a resounding ring of truth to it.

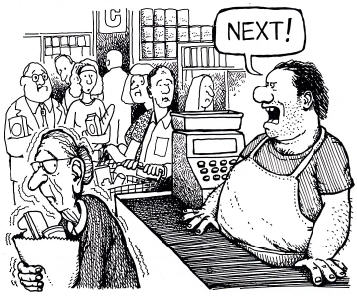

Across the land we hear the woeful tales: A plumber arrives only after your leaky pipe becomes a gush that floods the basement; a company representative leaves you on hold long enough to read this entire magazine; a banker treats your loan application like it's a demand for his personal fortune; a check-out clerk makes you feel it's your fault an item is not tagged with the price or department code; and at the restaurant the price is first class but all else is third class, or worse.

I have a tale of my own. In India last year I was held up for three days because an American airline did not inform an Indian airline, with which I had an onward ticket, that I'd arrived in Bombay, so I lost my seat and missed my connections. A mistake? Sure. And we all make one sooner or later, of course, but this time neither party accepted responsibility for the inconvenience and the expense to me and my family.

Since satisfied customers are the very bricks that build any solid service enterprise, one naturally wonders, "Why such slipshod service?"

I've heard a few explanations: "People just don't care anymore"; "It's a sign of the times; bad economy puts people on edge"; "This is the machine age; depersonalization has set in." All of these have some merit. But no analysis homes in on the problem as accurately as one based on the philosophy of Krsna consciousness.

Krsna teaches in the Bhagavad-gita that everyone in this material world is here primarily for sense gratification. That is to say, everyone came here from the spiritual world wanting to be served. No one came because of a desire to serve. Indeed, it was rebellion against serving Krsna we became envious of Him that got us out of His spiritual kingdom in the first place. We rejected Krsna's service, and, consequently, we had to leave the realm of pure consciousness and come to the mundane world, where we imagined we could set ourselves up as all in all. In other words, each of us came here on his own "god project."

Unfortunately our scheme is doomed. Our struggle for the post "Primary Object of Service" is very much like the fighting of nursery school kids over the same toy. I've even seen a bumper sticker that read, "The one with the most toys wins." Each child thinks he is more entitled to the toy than the others. Even if one child gets it, moments later he loses it to another. He ends up frustrated, depressed, and angry.

As adults vying for the most service for ourselves, we generally use more sophisticated "cultured" ways than kids: codes of dress, etiquette, modesty, and what have you. But, like everything material, the facade doesn't last. It eventually splits at the seams, and we glimpse the chaos behind.

The current crisis in the service industry is an instance of such a split. It holds no surprise for a Krsna conscious person. After all, when you consider that formerly we refused to serve Krsna, who is the all-attractive Supreme Person, the proprietor of all opulences namely fame, wealth, beauty, knowledge, strength, and renunciation why should we now want to serve anyone less qualified than He?

Rendering service, however, is unavoidable. Except for a distinction in motive and quality, rendering service is common to both the spiritual and the material worlds. In the spiritual world all service is rendered out of love, with full care and attention, without ulterior motive, and without cessation. Here in the material world, although the husband serves the wife, the teacher serves the student, the clerk serves the customer, the politician serves the public, and so on, the service is largely contingent on some sort of remuneration, some means to sense gratification usually money.

Service rendered on that basis is self-serving, or selfishness, performed primarily for the aggrandizement of the servant. But even our selfish motives do not instill in us a satisfactory service attitude. Thus we have a crisis in America's service industry. That's one excellent reason why we should practice Krsna consciousness: because rendering service to others with God in the center can alone inspire us to serve with care and attention, which is the way service ought to be done, every time.

The Law And The Profits

by Mathuresa dasa

Over the past twenty years Americans have been suing each other with increasing frequency and winning (or losing) a growing number of million-dollar settlements. Million-dollar verdicts rose from two in 1963 to 401 in 1984.

Although most of the plaintiffs in the more than 15 million civil suits filed each year have some legitimate grievance, the opportunity for easy riches lures plaintiffs and lawyers alike into using the tort system like a lottery: file the lucky suit, legitimate or not, and hit the jackpot.

Even when the grievance is clearly legitimate, awards are often outrageously high. This is particularly true when the plaintiff gets reimbursed for "pain and suffering" resulting from personal injury, from losing a relative, and so on. Pain and suffering are hard to measure, harder still to put a price on. Pain and suffering may also be invisible, and the court may have only the testimony of the plaintiff and his doctor or psychiatrist to go by. If the testimony is convincing and the judge and jury are sympathetic, the award can be astronomical.

Advocates of tort reform point out that since money can pay for medical bills, disabilities, or property damage but can't really allay pain and suffering per se, there should be a cap on awards. Colorado has already passed a law limiting compensation for pain and suffering to $250,000. In other states similar legislation is pending.

In the Bhagavad-gita Arjuna comes to a similar conclusion about the efficacy of money in eliminating suffering. Faced with the painful possibility of his relatives being killed in battle, Arjuna declares that his entire kingdom (what to speak of a few million dollars in tort awards) would appear worthless to him if his loved ones died.

Commenting on this part of the Gita, Srila Prabhupada explains that no amount of wealth can eliminate life's problems. By economic means alone we cannot succeed in making ourselves or our families happy. Even if we can afford the good things in life, we have to face the miseries of disease, old age, death, and rebirth, as well as a host of lesser afflictions law suits among them.

Every one of us is trapped in the painful cycle of repeated birth and death. To become free from this repeated suffering we have to take shelter of Lord Krsna, as Arjuna did. "Those who worship Me," says Krsna in the Gita (12.6), "being devoted to me without deviation, … for them I am the swift deliverer from the ocean of birth and death." Surrender to Krsna is the only way to escape misery.

This should be a lesson not only for plaintiffs with legitimate pain and suffering, but also for plaintiffs and lawyers who are merely playing the tort "lottery." After all, everyone is trying to escape suffering of some sort, and everyone thinks money is the solution.

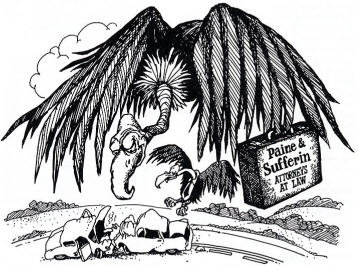

For instance, an American lawyer has to pay bills, taxes, mortgages, and so on, just like everybody else. To avoid the pain and suffering of not being able to afford all these things, he has to compete with 700,000 other American lawyers (which is two-thirds of all the lawyers in the world) and he also has to charge exorbitant fees. Legal expenses eat up about two thirds of all tort settlements.

In fact, the overabundance of lawyers is often cited as the primary cause of the tort crisis. Just as having too many surgeons may lead to unnecessary operations, so having too many lawyers leads to phony lawsuits.

I have a relative who was persuaded by a lawyer to file suit against one of her former friends. "If we win," the lawyer told her, "you can get rid of your old VW bus and buy a brand new Cadillac." A year later when my relative relented and decided to call off the suit, the lawyer delivered his ultimatum: either pay my legal fees for the past year or let me finish the suit and take my fees from the settlement. So the suit was really the lawyer's from beginning to end, and the "grievance" is the lawyer's crying need for money, which he mistakenly feels will end his own pain and suffering.

So the tort crisis might diminish if plaintiffs, lawyers, judges, and juries learned to rely on the court system only for reasonable payment of tangible expenses like medical bills and property damage and for payment of reasonable legal fees, while learning to rely solely on Lord Krsna for the ultimate alleviation of all pain and suffering.