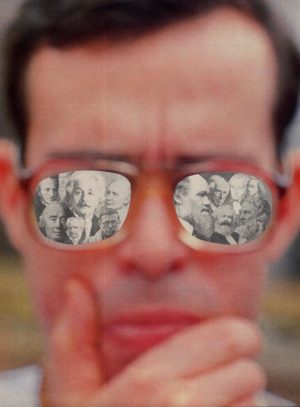

Ignoring a most important avenue of knowledge, Western philosophers have left us with

a hazy conception of the Absolute Truth.

A frequent criticism of the Krsna consciousness philosophical tradition is that it places too much emphasis on authority. This is not surprising, seeing as how philosophy in the modern world is based on a revolt against authority. And yet we gain a considerable amount of our worldly knowledge from authorities the media, schools, libraries, doctors, lawyers, and other experts. Devotees of Krsna consider this inconsistency between philosophical ideal and practical experience absurd. If authority is a valued source of our worldly knowledge, then how much more essential it must be in matters of a supra-sensory nature. From the Vedas we learn that without authority there is no real possibility of our penetrating the maze of relative truths in this world and reaching the Absolute Truth in the transcendental world. And it is precisely this Absolute Truth that we desire so much in our quest for certainty.

Our quest for certainty is part of the age-old effort to transcend belief. As the seventeenth-century French philosopher Blaise Pascal observed, we are not satisfied arbitrarily accepting any system of dogma to live by. We want to justify to ourselves and to others why we adhere to this or that particular set of values. We crave certainty. We want Truth the kind of Truth that Pascal described as "invincible to all skepticism."

Yet ironically, despite our yearning for Absolute Truth, most of us limit ourselves to two sources of knowledge that for centuries philosophers and scientists have known yield results that are far from "invincible to all skepticism." These sources are sense perception and inferential logic. Both rely on our sense organs, which are defective and unreliable. All of us have had the experience of being deceived by our senses. Perhaps we saw a mirage, or a stick that appeared bent because it was half immersed in water. There are many similar examples. And the process of inference, because it relies on our faulty sense perceptions, is also unreliable as a source of certain knowledge.

In support of the above conclusions, the Vedas list four characteristic defects that vitiate the reliability of all knowledge gained by perception and inference. First, we all make mistakes "To err is human." Second, we are all subject to illusion. Third, everyone has limited senses. Finally, everyone has the propensity to cheat. By their very nature, therefore, perception and inference fail to provide us access to the Absolute Truth. If we rely only on them, our quest for certainty is at a formidable impasse.

Some philosophers see this impasse, and being unaware of any alternative to sense perception and inference, they conclude that indubitable knowledge is impossible. These skeptics argue that even if there is a metaphysical truth underlying physical reality an ultimate cause of existence it is unknowable in any factual or verifiable sense because we have no access to it here in the world of phenomena. Therefore all metaphysical pursuits are futile. At best we can only conceptualize the Absolute in terms of our human experiences. But the Absolute may be entirely different from our human notions, and since we can never verify our speculations one way or the other, it is far more pragmatic to work cooperatively for the realization of humanistic ideals.

A good many people are taken in by this argument, but it has a serious flaw. The skeptics' declaration that we can never acquire knowledge is an example of the very thing they attempt to deny: an assertion of certain knowledge. In other words, it would take perfect knowledge to know there is no perfect knowledge. This is patently absurd, and thus extreme skepticism refutes itself. We can conclude only that some sort of indubitable knowledge is possible. Our task, then, is to investigate further for a source of knowledge more reliable than perception or inference.

To date in the Western world, a plausible alternative to these has not been devised. The Vedic literature, however, recommends a third source of knowledge: sabda-brahma, hearing from transcendental authority. The Vedas consider sabda-brahmamore reliable than perception or inference because it conveys knowledge free of all defects. Please note, however, that the Vedas do not dispense entirely with reason and experience. What they question is the validity of these methods in matters that do not fall within the range of reason and experience.

Some of the premises of the Vedas theory of knowledge are as follows: The Absolute Truth is that from which all else emanates; the Absolute Truth is inconceivable; that which is inconceivable can't be understood by any amount of mental speculation; the Absolute Truth can be understood only if it chooses to reveal itself. Now, keeping in mind that absolute means unlimited, unconditional, complete, perfect, unadulterated, and so on, let us carefully try to understand how one can realize the suprasensory Absolute Truth by the process of sabda-brahma.

The Vedas explain that because the Absolute Truth is the source of everything, all qualities, attributes, and varieties found in this world must innately exist in it. Otherwise, it could not be defined as complete, unlimited, and so forth. If everything originates from and inheres in the Absolute Truth, then personhood or personality must also be among its innumerable features. And since the Absolute Truth is transcendental, its personal feature must be a transcendental person.

Of course, a suprasensory Absolute Person is completely inconceivable in terms of our present mundane experience. But the consequence of denying the possibility of His existence is extremely grave. We are obliged to allow, at least theoretically, that a transcendental Absolute Person can exist just to fulfill the literal meaning of the term "absolute." The moment we deny personhood to the Absolute Truth, we immediately try to impose limitations on the Unlimited. We try to make the Inconceivable conceivable, the Complete incomplete.

A great many thinkers have difficulty coping with the Vedas' assertion that the Absolute Truth is a person. Though they readily agree that absolute means "unlimited," "complete," and so on, they somehow retain a limited conception of the Absolute. They speculate that the Absolute must be some sort of all-pervading, infinite, undifferentiated, impersonal, metaphysical substance a "Oneness" devoid of any personal characteristics.

These impersonalists, as they are called, generally derive their conception of the Absolute in response to the variegated nature of this world. Metaphysical reality, they reason, must be the complete opposite of physical reality. Therefore it must be formless, homogeneous, subjective, and impersonal.

The Vedas, however, explain that the complete Absolute includes both the personal and the impersonal aspects. By way of analogy, consider the sun. The sun is like the personal feature of the Absolute, the sunlight like the impersonal feature. Both exist simultaneously as the energetic source and the energy, but one is localized, the other expansive and all-pervasive. Similarly, the Absolute Person exists simultaneously with the impersonal Absolute. This is necessarily true, although paradoxical, because the source of all emanations must simultaneously contain and reconcile all contradictory notions.

The Vedas give numerous details about the name, form, qualities, pastimes, and entourage of the Absolute Person. His name, we are told, is Krsna, the All-Attractive One. His transcendental body is made of eternality, knowledge, and bliss. No one is equal to Krsna or greater than Him. He is the prime cause of all causes. His transcendental abode in the spiritual realm is far, far beyond the material realm. There Krsna always revels in transcendental loving exchanges with His pure devotees. These relationships are untainted by mundane feelings such as envy, hate, anger, fear, illusion, and lust.

From time to time, Krsna manifests Himself within the physical world and enacts many wonderful, incomparable pastimes. He also delivers to human society knowledge of the Absolute Truth unavailable from any other source. Krsna does not have a material body. Thus He is never afflicted by any of the four human defects. He is absolute, and His words are absolute. For this reason, His devotees accept the scriptures spoken by Krsna, such as Bhagavad-gita, as authoritative and perfect absolute knowledge. Hence the basis of scriptural authority for Krsna conscious persons is the Absolute Truth Himself.

Since I used the Vedas as the reference to establish the personhood of the Absolute Truth and the authority of Bhagavad-gita, one may naturally wonder about the basis of the authority of the Vedas. The Vedas themselves explain that they emanated from the Absolute Truth. They are not man-made. And in the Bhagavad-gita (15.15) Krsna says, "By all the Vedas, I am to be known. Indeed, I am the compiler of Vedanta, and I am the knower of the Vedas."

Still, some philosophers try to discredit the Vedas' claim that they rest on the authority of the Absolute Truth. These thinkers sometimes cite the fallacy of circulus in probando, circular reasoning, to refute the Vedas' claim. They object to the fact that theVedas refer to themselves to give evidence for their authority. The argument looks something like this:

A: Krsna is the Absolute Truth.

B: How do you know this is true?

A: It is stated in the Vedas and the Bhagavad-gita.

B: How do you know they are reliable?

A: Because Krsna spoke them.

In logic this type of reasoning is not admissible evidence. But when the discussion is about evidence for the Absolute Truth, this argument is valid. Logical reasoning dictates that there can be no source of verification for the Absolute Truth but the Absolute Truth Himself. Furthermore, these philosophers overlook that the Vedas' claim albeit an astounding one is completely consistent with the premise of its theory of knowledge: that knowledge of the suprasensory Absolute can come only from the Absolute Himself. In this particular instance, therefore, the fallacy of circulus in probando does not apply.

There is another important reason why the fallacy of circular reasoning is not applicable in this case. The Vedic literature gives a scientific methodology whereby one can test its theory of knowledge. All sages and saintly persons who followed the Vedas'recommendations to the point of mature transcendental realization such as Narada Muni, Madhva, Ramanuja, Sri Caitanya, and His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada all confirm that the Vedas emanated from the Absolute Truth, and that the Absolute Truth is Krsna.

The knowledge Krsna reveals about Himself in the Vedas is as good as His autobiography. Krsna is the superexcellent authority and the last word on Himself, just as Shakespeare is the last word and authority on himself. Devotees find no contradiction or fallacious reasoning in the theory that transcendental knowledge must come from transcendental authority. Rather, they find it sublime. It is so sublime that even if you withdraw the support of the Vedas, it still stands up to the critical examination of reason.

The final point concerning the theory of sabda-brahma is understanding the authority of the guru, the spiritual master. Lord Krsna, besides being the basis of authority for the scriptures, is also the authority for the disciplic succession of gurus. He explains this in the Bhagavad-gita. He is the original guru, having enlightened Lord Brahma with transcendental knowledge. Lord Brahma enlightened Narada Muni, whose disciple was Vyasadeva, and so on down to the present day.

Transcendental, indubitable knowledge is first given by Lord Krsna and then transmitted as it is without any adulteration through the disciplic chain. Each guru repeats the message in just the way he heard it from his predecessor guru.

Hearing from the lips of a bona fide spiritual master is as good as hearing from Krsna directly. The guru's teachings and behavior must be in consonance with the Vedic version. The moment a "guru" deviates from this principle, the disciple is no longer obligated to follow him.

In the Vedas, Krsna repeatedly exhorts us to seek out a bona fide guru, surrender to him, and please him by submissive inquiry and service. In this way the disciple gradually transcends all material limitations of his senses, mind, and intellect. Then by spiritual cognition, called vaidusa-pratyaksa, he can see Krsna face to face. But he can be successful in this endeavor only if he humbles himself before the authority of scripture and the authorized spiritual master.

Actually, accepting authority is the universal principle in learning virtually any subject. Granted, authority has been corrupted and abused in the past and it certainly will be in the future but the validity of the principle still stands. Hundreds of years of philosophical speculation have not produced a more feasible method for understanding the Absolute Truth than sabda-brahma.

Those who think the process of Krsna consciousness places too much emphasis on authority would benefit immensely by studying the Vedas' theory of knowledge. They would be pleased to find it "invincible to all skepticism," although on a personal level they may balk at accepting the discipline. That raises a question of their integrity. As far as the quest for certainty is concerned, there is simply no other way to get around the impasse created by perception and inference. Sabda-brahma has been tried and proven true. It does deliver the indubitable Absolute Truth.