Durban’s Sri Sri Radha-Radhanatha Temple of Understanding opened thirty years ago, after many struggles during South Africa’s apartheid era.

A Rainbow never ceases to capture my eyes and dazzle my mind. It inspires thoughts of eternity and freedom, and even of another world beyond it. I am part of the diverse spectrum of people who make up the Rainbow Nation, a term for post-apartheid South Africa signifying peace and unity. Proposals for creating peace and unity in South Africa, however, are of limited value if based on material, rather than transcendental, vision. Only the sun can create a true rainbow, and on the horizon of Durban I see the Sri Sri Radha-Radhanatha Temple of Understanding blazing like a sun, radiating spiritual knowledge to all South Africans. This knowledge – of God and our relationship with Him – gives rise to spiritual freedom, to the end of the soul’s captivity in this world, to eternal life in God’s kingdom. The rainbow’s power to captivate us lies not so much in the colors themselves as in their harmonious combination created by the sun. The sun of spiritual understanding can harmonize the diverse colors of the Rainbow Nation, creating a captivating display of unity in diversity in service to God.

The Temple of Understanding has shed its light for thirty years as if untouched by time. I perceive it as a gigantic golden lotus opening its petals on a dazzling pond, or a celestial aircraft that has descended and landed on an ordinary spot. The temple’s architectural perfection intrigues me with its fusion of traditional and modern design. Towering above the shimmering octagonal roof, gold-leaf-edged domes display tilaka-shaped windows that delight the eye and the soul. Austrian architect Rajarama Dasa conceived the design, which follows principles of the Vedic Śilpa-śastra. The building’s very layout is meant to teach spiritual truths – and to suggest stories of courage, determination, and hope.

The temple’s story began in the 1970s, when South Africa, unlike the rest of Africa, was a land of plenty. Its booming economy, fertile landscapes, temperate climate, and rich heritage painted a beautiful picture.

But looking closer, we see the picture scathed by racial discrimination and ethnic divide. People of different races, colors, and cultural backgrounds lived under the banner of apartheid (“apartness” or “separateness”), the policy of racial segregation that forced whites and nonwhites to live separately and inflicted unfair treatment on the “lesser races” of Africans, Indians, and Coloreds (of mixed race). Violence and bloodshed stained the colors of the rainbow.

Elsewhere, Srila Prabhupada had founded his International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) in 1966. Circling the globe repeatedly, he brought together people from many countries and ethnic and religious backgrounds, unifying them on the principle that as spiritual souls we are one in the eyes of God and can unite in service to Him. Srila Prabhupada often commented that ISKCON was the real United Nations.

Srila Prabhupada’s Emissaries Arrive

Following in Srila Prabhupada’s footsteps in creating awareness of universal spiritual brotherhood, a few of his disciples, headed by Ksudhi Dasa, arrived in South Africa in 1972 to start the Society there. They were wary of the political turmoil, yet unafraid. Srila Prabhupada had spoken of how his guru, Srila Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati, had convinced him that spreading Krishna’s message could not wait for India’s independence. Prabhupada’s example inspired his missionaries to South Africa, but they wondered how they could spread Krishna consciousness when they were forbidden to mix with nonwhites, the majority of the population.

These pioneer devotees endured countless struggles and challenges, risking their lives to spread the message of the Bhagavad-gita. Some were persecuted and imprisoned, others deported. Somehow they were able to reach out to people and win their favor. The Gujarati community provided shelter in their homes, shielding the devotees from the oppressive government. Eventually the devotees had to run from the secret police, so they traveled from town to town and set up hall programs in the Indian districts. Still, they needed a base, a place from which to freely propagate their mission.

Srila Prabhupada had opened temples and bhakti-yoga centers in many parts of the world, and he hoped the same could be done in South Africa.

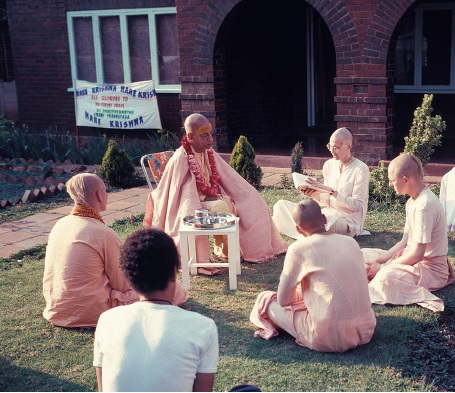

Even though a center was eventually established in Yeoville, near Johannesburg, Srila Prabhupada envisioned something greater. Visiting the country in October 1975, he saw a fertile ground in which to plant the seeds of Krishna consciousness despite the challenges the devotees faced.

“When Srila Prabhupada visited,” recalls Partha Sarathi Dasa Goswami, one of the pioneers in South Africa, “there was no integration of races, so in his lectures he strongly emphasized that we are not a man or a woman or black or white but we all are eternal servants of God, and therefore equal. In that political climate, stressing equality was controversial, but Srila Prabhupada fearlessly spoke about this from Bhagavad-gita, Chapter Two, at public programs at the Durban City Hall, with over two thousand people attending, and at the University of Witwatersrand (WITS), addressing students and lecturers across the racial divide.”

Srila Prabhupada’s disciples tried to boldly spread Krishna’s message as their spiritual master was doing. Along with a few other devotees, Gokulendra Dasa, the first South African to join ISKCON, approached the chief registrar in Pretoria to register the society as the International Society for Krishna Consciousness. The government was cautious about allowing international organizations into the country, fearing they would encourage free mixing of races. So the registrar refused; he said it had to be registered as the “Society for Krishna Consciousness in South Africa.” After Gokulendra failed to convince him otherwise, he remembered the Simply Wonderfuls (round butterand- powdered-milk sweets) he had brought, and he slipped some onto the registrar’s tea plate. While the haughty official drank his tea, he looked at the sweets, picked one up, and took a bite. As he savored the delicious prasada, he turned to his secretary and said, “Give them their name.”

Shortly afterwards, a 120-acre farm in Cato Ridge became the main center and haven for the devotees. Living in the countryside ensured less resistance to their efforts and more freedom to approach the mixed races. Partha Sarathi Dasa Goswami started “tent campaigns,” traveling with others to different areas in the province, setting up a tent, and inviting people to an evening of spiritual discourses, dramas, kirtana, and prasada. These programs inspired many from the Indian community to become committed devotees. The devotee farm community grew, but still a temple closer to a city was needed.

In the meantime, the government discovered that many foreign devotees, routinely denied missionary visas or extensions on their tourist visas, were living illegally in the country. The devotees risked being prosecuted and deported. Tulasi Dasa, the Cato Ridge temple president, reported this injustice to the Leader, an Indian newspaper. The Leader ran an article exposing the devotees’ plight, causing an uproar among the Indians. Mr. Rajbansi, a member of parliament who represented Indians, submitted an official plea to the government. But the government had to be cautious. It was creating a tricameral parliament; although still white dominated, it would give a limited political voice to the country’s colored and Indian groups. The government withheld judgment for a year, and then, to gain favor with the Indian community, it issued work permits to the devotees. Now the foreign devotees’ stay was unhindered.

Selfless Efforts To Build the Temple

The need for a central base kept growing. Finally, in 1980, Mr. Rajbansi helped the devotees procure a large piece of land in Chatsworth, on the outskirts of Durban. There a temple like no other in the southern hemisphere would be built. ISKCON’s Governing Body Commissioner (GBC) at the time, Bhagavan Dasa, saw the temple as the way to convince the government that ISKCON had a prominent role to play in the country. Together with Tulasi Dasa, the coordinator of the project, he urged the devotees to stop their other activities and start fund-raising.

“We loved to speak to people about Krishna and distribute Srila Prabhupada’s books,” Ramanujacarya Dasa explains, “but to build the temple everything had to stop, and some of us had to sell oil paintings. We had to grow our hair and replace our devotional attire with smart Western dress. We set up shops to sell paintings, the main method of collecting funds. We also had groups of devotees traveling throughout South Africa and Namibia, soliciting donations and selling paintings.”

Sri Murti Devi Dasi, one of the first Indian women to join at Cato Ridge, described the new-temple project as a war, so great were the devotees’ sacrifices. For example, her late husband, Śyamalala Dasa, was traveling in a remote part of the country to collect funds when his car went over a cliff. For days, no one knew where he was. But Krishna had saved him.

Today, when I look at the goldrimmed tilaka windows on the domes, I see the devotees’ faith and devotion reflected in them. Tilaka, the markings on a Vaisṇava’s body, symbolize victory by the Lord’s protection. The devotees trusted Krishna’s protection and knew their success depended on Him. But the tests didn’t end. Money was scarce and living conditions austere. The devotees didn’t give up. They formed their own construction company, and with much effort a temple started to emerge.

Nandakumara Dasa, one of the first presidents of the Temple of Understanding, recalls, “The gold leafing of the tilaka windows and of the base of the spires took place early in the morning when it was still dark and there was no wind. The gold leaf was thinner than paper, and there had to be no wind so that it could not fly away or get spoilt whilst we tried to ‘paint’ it on. We were thirteen floors up on scaffolding, without any safety measures in place. It was quite daunting and scary, as we had to use both hands while trying to balance on the metal piping that made up the scaffolding.”

The devotees spent days focusing on the task, and the tilaka on the domes began to shine.

“During the initial part of the construction, there was a drought,” says Ramanujacarya Dasa, speaking of how Krishna responded to their efforts. “No rain meant the construction could go on unimpeded. Also, the water meter broke, which reduced our costs for the tons of water we were using for the construction. No doubt Krishna was helping us.”

The devotees were soon to see the Lord for whom they had made difficult sacrifices. Sri Sri Radha- Radhanatha, forty-two-inch marble deities of Radha and Krishna , arrived in South Africa from Jaipur, India. The late Bimala Prasada Dasa, the head pujari, had overseen the sculpting, arranged the safe transport of the deities, and dealt with customs and other complications.

The Installation: October 1985

Finally, the day arrived for the grand installation, and 1985 summoned a new hope for the Rainbow Nation when thousands of people thronged to the two-day event. The visitors flooding through the entrance gate, crossing the bridge, and entering the temple didn’t know they were leaving the Iron Age, crossing the bridge of material life, and entering another realm. But when they entered, they felt the transition. The air was thick with a spiritual presence. Everyone was mesmerized by the octagonal temple floor covered in cream-colored marble, the hundreds of mirrors adorning pictures of Krishna’s pastimes, the dazzling chandeliers hanging below eight panels of three-meter-long Krishna paintings, and the thousands of lights that lit up the floral designs and intricate artwork. Madhavendra Puri Dasa, the interior designer, used materials from all over the world to create the stunning effect.

Standing amid this artistic splendor, the devotees focused their eyes on the altar. There, on large lotusshaped bases, stood the charming forms of Sri Sri Radha-Radhanatha and Sri Caitanya Mahaprabhu. Adding to the devotees’ excitement was the news that a sacred thread on Lord Radhanatha’s body had revealed itself. Surely this was a sign of His pleasure and His reciprocation with the devotees for their efforts.

At the opening ceremony, guests and devotees from around the world listened to talks by leaders of the movement and the country. The speakers assured the audience that Krishna consciousness would now spiral to new heights in South Africa.

Better Times, But Challenges Remain

“Apartheid continued for some years after we opened the temple,” says Bhakti Caitanya Swami, a pioneer in ISKCON’s development in South Africa and now one of the two GBC representatives for the country. “In 1988, when I was regional secretary for Gauteng and temple president of the Muldersdrift/Johannesburg temple, we were prosecuted for allowing nonwhites to live in the temple or attend programs there. We had to stop nonwhites from coming, or face fines for each day we allowed them to come. Fortunately, the idea of the racial laws being dropped was becoming more and more accepted. None of the law authorities showed up for the hearing, and the whole matter was dropped.”

Today, racial prejudice is not the challenge it was then.

“South Africa is an extraordinary country, in which there is great diversity amongst the people,” Bhakti Caitanya Swami continues. “Not only are there black African people, white people, Indian people, and colored people, but even within each group there is great diversity. Through Krishna consciousness all these different people can live together and engage in devotional service happily, without worrying about the differences. In this way ISKCON in South Africa is a wonderful display of unity in diversity.”

The Sri Sri Radha-Radhanatha Temple of Understanding continues to help unify the colors of the Rainbow Nation. Even though Indians predominate at the temple, its activities touch people of all races. Devotees go out into the streets to share Krishna’s message with anyone interested to hear it. Busloads of schoolchildren and other tour groups from all ethnic and religious backgrounds enjoy temple tours, and many of the guests – especially the children – respond loudly to the chanting of Krishna’s holy names. Tribal groups in traditional costumes have chanted and danced before the deities.

The temple has given prominence to the province by winning the Kwa- Zulu Natal Landmark Tourist award for 2013, but those who worked to build the temple see its real value. As the devotees celebrate its thirtieth anniversary and the fortieth anniversary of Srila Prabhupada’s visit, the resplendent temple continues to radiate the same message at the dawn of new struggles in the Rainbow Nation. Political instability, the increase of crime, and other crises in the country show that our internal enemies – lust, greed, anger, pride, selfishness, and envy – must be eliminated. Only spiritual understanding and practices will conquer these treacherous enemies, the roots of the evils of society. Fortunately, the Lord’s holy names resonate from the Sri Sri Radha- Radhanatha Temple of Understanding, purifying the atmosphere and the hearts of those who hear it. With God in the center, a bright rainbow shall paint the sky.

Nikunja Vilasini Devi Dasi, a disciple of His Holiness Giriraja Swami, lives with her husband and two children in Durban. She writes for Hare Krishna News (a local publication), and is writing books for children and young adults, which she plans to publish.

The author offers thanks to Svarupa Damodara Dasa (former temple president), who gave advice and ideas for the articles, to his wife Sukumari Devi Dasi, who transcribed the interview, and to all those who submitted photos and information. Thanks to Riddha Dasa for his book Mission in Service to His Divine Grace, which provided the historical timeline and some of the initial historical information. A special thanks to Rasa-sthali Devi Dasi for her encouragement and support. She edited the interview, coordinated photos, and helped in gathering information and communicating with devotees.