"Thinking myself in the company of a fellow truth-seeker, I decided to impress him with my views of the truth."

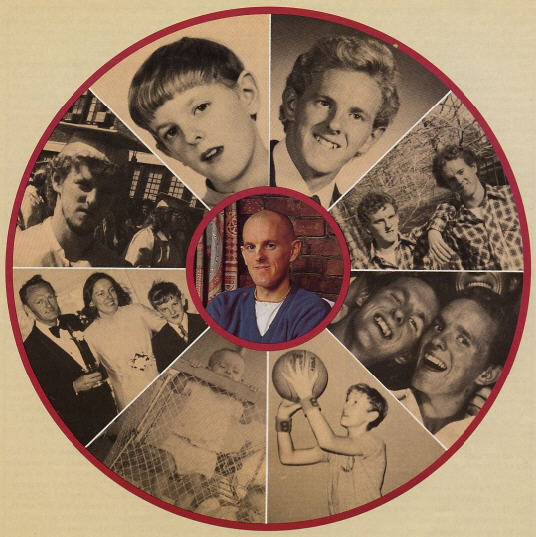

I lay on the ground near my home in Newark, Delaware, "just thinking" one autumn day in 1980. In the distance I saw my twin brother running down a cross-country path. I watched as he disappeared from view, and I thought of how time was separating our courses of life and of how it would eventually separate us forever. I felt sad. Does life have a purpose? I wondered. So often it seemed pointless. Cruel. Confusing. I had no answer. But I decided that if I ever came across the answer, I would live for it.

Although I grew up a Catholic and attended mass with my family every Sunday, God was a distant figure, and my Sunday excursions were a ritual I endured. So, by the time I left home for college, I had stopped going to church. I had decided I was no longer going to be a blind follower.

After two years at Black Hills State College in South Dakota, I returned home and enrolled as an art student at the University of Delaware. My grades were all right, but college was mostly another ritual. And I had no firm career plans. Some friends suggested perhaps I was asking too much from life to find "the purpose."

I read a lot of Thoreau and Whitman and took heart. They advocated the reality of individual experience and condemned conformity. I was moved by their spirit to experience life. Thoreau advised, "Live deep, and suck out all of the marrow of life." Sounded good, though he never concluded what that "marrow" was. And although Whitman was idealistic, he admitted, "I have not once had the least idea who or what I am."

One October afternoon my brother brought home some Back to Godhead magazines and a few other Krsna consciousness books. He told me he had met a shaven-headed man in robes who said that this literature contained the Absolute Truth. We both read the books and magazines, and I was immediately impressed by the depth of spiritual knowledge. What impressed me most was the well-reasoned presentation of how ordinary people can learn to live a God-centered life.

I decided to visit the nearby temple, where I met a devotee named Kalakantha dasa. I spoke with him at length and appreciated that although he was religious, he unlike other "religious" persons in my experience was not contemptuous. He treated me cordially as a guest, and during our conversation he spoke intelligently and candidly about his religious convictions. He did not stress faith without reason; rather, he backed everything he said with sound philosophical arguments.

One especially convincing point Kalakantha made was that everyone renders service to someone. The wife serves the husband, the employee serves his boss, the president serves the nation, and so on. Since it is our nature to serve, he explained, it is in our best interest to find the most rewarding person to serve. That person is God, Krsna. Serving Krsna fulfills all our desires, just as watering the root of a plant nourishes the entire plant. Krsna is the root of our existence.

Out of curiosity I asked Kalakantha what was required to join the organization. He told me of their restrictions: no gambling, no illicit sex, no intoxication, and no eating of meat, fish, or eggs. And every member must vow to chant the Hare Krsna mantraa prescribed number of times daily. I was surprised to hear of such strict principles, and I thought there must be some merit to the process. I had never heard of people living by such high standards.

When Kalakantha asked me what I wanted to do with my life. I expressed no particular ambition. I said my peers considered me unsociable, but that I couldn't conform just to please them. I found myself in a recurring quandary: whether or not to pursue interacting with others. Kalakantha could understand my predicament, and he explained that helping people to understand their real identity as eternal souls was a worthy reason to pursue relationships. This made sense to me. I was impressed that he didn't look down on me for my unsociable tendencies. Rather, he stated indirectly that without pursuing knowledge of self-realization, social exchanges were inconsequential; they were largely just forums for ego gratification.

Kalakantha introduced me to the Hare Krsna maha-mantra: Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. Although the philosophy of Krsna consciousness interested me, this aspect of it seemed superfluous. I knew a little about mantras, and I knew that they supposedly made one more energetic, proficient, and enthusiastic about whatever one aspired for. But I was doubtful. Besides, I didn't know for sure what was really worth aspiring for. Onemantra meditation group I had already visited wanted $150 for my "personal mantra." But Kalakantha offered me the Hare Krsna mantra free.

He explained that the chanting of the Hare Krsna mantra was the primary means for reviving our dormant God consciousness. We already have a relationship with God, he said, but we have forgotten it. By chanting Hare Krsna, we purify our consciousness and reawaken our original knowledge of God. This was a new concept to me, but it seemed a higher ambition than using a mantra to increase one's prowess.

We then entered a room where there were musical instruments. Kalakantha played a harmonium (a hand-pumped organ) and sang the Hare Krsna mantra, while I responded: Hare Krsna, Hare Krsna, Krsna Krsna, Hare Hare/ Hare Rama, Hare Rama, Rama Rama, Hare Hare. I appreciated my host's ear for music, but it was the sincerity of his chanting that impressed me most: it was not a performance, but glorification of the Supreme Lord.

With reverence I immersed myself in the mood of the chant as Kalakantha had described it to me: "My dear Lord Krsna, please engage me in Your service." Very soon I experienced a change in consciousness. My usual concerns and anxieties became irrelevant, and I felt aloof from the influence of the external world. Following Kalakantha, I carefully enunciated each syllable of the mantra, meditating on its meaning. What else could I be meant for, I thought, than to engage in God's service?

Afterwards, I promised Kalakantha I would return Sunday for their weekly festival. I chanted all the way home.

During the next few days I read the first volume of the Srimad-Bhagavatam. Unlike with Thoreau and Whitman, here I found answers. Everything seemed to relate to my deepest, most persistent questions about the purpose, the "marrow," of life. I came across this verse:

Your questions are worthy because they relate to Lord Krsna and so are of relevance to the world's welfare. Only questions of this sort are capable of completely satisfying the self. Bhag. 1.2.5

It reminded me of what Kalakantha had said about how only discussions concerning self-realization were of consequence. I became hopeful that life did have a specific purpose. Somehow I had found what just might be the greatest discovery of my life.

I returned to the temple for the Sunday program and noticed that the majority of guests were Indians. It was a slight "culture shock" for me, but I appreciated their mannerly behavior. Seeing so many Indians impressed on me that Krsna consciousness was not just a fad, but it had cultural roots and a substantial following in India.

The devotees interested me, and their books were convincing. But what about their lives? Were these people finding the deep fulfillment I had read about in their books? They certainly seemed dedicated. They were always ready to answer any philosophical inquiry and they made every effort to see to the satisfaction of their guests. They were active, yet not ambitious for ordinary remuneration or recognition. During the feast the devotees waited on me, serving me whatever dishes I might want more of. They even teased me, persuading me to eat until I could barely get up. I had nothing to offer them in return, but still they selflessly served me (and many others) with obvious satisfaction. Clearly, they were happy in Krsna consciousness, and their primary concern was for others. Never had I seen such conviction. The devotees were the most secure persons I had ever met.

Kalakantha showed a film that described the soul (or self) as a spiritual spark of consciousness. The soul was unaffected by material qualities. Designations such as "man," "woman," "black," "white," "young," "old," "American," "Chinese," and so forth had to do with the temporary body, not with the eternal soul. As I watched the film, I was deeply impressed. Never before had such ideas occurred to me. Without the soul, the body was just a lump of dead matter. The soul doesn't die; it transmigrates to a different body. Only when the soul reawakens his original relationship with the Supreme Soul, God, can he be relieved of the inconvenience of accepting another material body. This reasoning was theoretically acceptable to me. I was becoming convinced that Krsna consciousness was the solution to the mystery of life.

The next two mornings I attended classes on the Srimad-Bhagavatam. On the second morning I stayed after class to get a set of japa beads from a devotee named Baladeva, who showed me how to chant on the beads. Thinking myself in the company of a fellow truth-seeker, I decided to impress him with my views on the truth. I said that by confronting surprises and adversities in life one could grow to be able to weather any calamity; and in such a state, one would become indifferent to miseries and thus enjoy life.

Baladeva then explained that there were two ways of acquiring knowledge: by the ascending process and by the descending process. The ascending process was the empirical method, gaining knowledge through the senses. The descending process was the method of acquiring knowledge by hearing from higher authority. Empirical knowledge, Baladeva explained, is never complete or conclusive. Better to hear submissively from a learned transcendentalist in disciplic succession who has realized the Absolute Truth.

But I was stubborn. For the next three hours I argued with Baladeva, insisting on the value of my subjective experience. Not only was he unimpressed by my arguments, but he dismantled them one after another. He pointed out that experiences in this world were short-lived and they never added up to a solution to life's problems. He defined life's problems as disease, old age, repeated birth, and death, and he explained that if I did not use my human energy to develop self-realization, or knowledge of my ultimate relationship with God, then I was essentially no better than an animal. A human distinguishes himself from the animals when he uses his superior intelligence for understanding his eternal relationship with God. If he denies this opportunity, he lives only a "polished animal life."

I knew I was defeated. I had been humbled. Although I was proud of my acquired wisdom, I realized I was merely speculating on things beyond my mind and senses. Feeling embarrassed, I left the temple without saying when I would return. But I knew my life would never be the same.

My reading of the Bhagavatam, my observations of the devotees, and my discussions with Kalakantha and Baladeva had convinced me of two things: I had an eternal relationship with God, and up until now my life had been in ignorance. Now that I had found the truth, how could I go on living in blind defiance? The answer was obvious. That night I moved into the temple, and I've never looked back.