On the day the giant South Works of U.S. Steel closed last year, a cortege of automobiles formed at the Local 65 union hall in Chicago. The drivers, many of whom had been employed by U.S. Steel since the Second World War, drove in procession to the South Works' gates for a farewell visit to the machine shops, welding shops, and furnaces, where they had spent so much of their lives. They felt they had lost not only their jobs but a dear friend.

In the past ten years, U.S. Steel, Interlake, LTV, and others have laid off thousands of workers at mills across the country. In some parts of the country, factory closings by U.S. Steel and consequent, foreclosures on steelworkers' homes have prompted angry demonstrations and even threats against the lives of U.S. Steel executives and their families, "You have profited so much from our labor," the steelworkers are in essence saying, "how can you now leave us out in the cold?"

Steel executives might reply that workers have also profited. It is in large part the high wages demanded by unions that have given foreign companies a competitive edge and put American manufacturers out of business. Out of the steel business anyway. The difference between the companies and the workers is that many companies have been able to shift their capital into oil investments and other pursuits, whereas the workers have no such alternatives.

On the one hand, we could side with the workers by arguing that steel companies, or employers in general, ought to guarantee not only good wages but job security as well. According to the Vedic social system called varnasrama,employers should look upon workers as family members, caring for them as they would for their own relatives. How can we coldly view laid-off workers as inevitable fatalities of the free-market system, letting the welfare of an individual or a community be determined by profit-margin calculations?

But on the other hand, there's more to be considered than simply the question of job security. Even with a big weekly paycheck, a steelworker's living conditions are hardly ideal. The south shore of Lake Michigan, for example, is both the most highly industrialized area in the world and one of the most blighted. In neighborhoods with names like Irondale and Slag Valley, rows of bungalows stand right outside factory walls, where chemicals rain from factory smokestacks and fine gray grit from nearby slag dunes fills the air.

After they've worked all day in smelters and machine shops, this is what steelworkers come home to. Former employees of South Works may have fond memories of their years there, and fonder feelings still for their homes, but such living and working conditions nevertheless take their mental, physical, and spiritual toll.

The obligation of employers to treat employees like family members is hardly fulfilled by assuring workers job security in manmade hells. According to thevarnasrama system, the emphasis in any economic system should be on agriculture. The necessities of life grains, fruits, vegetables, milk, cotton, wood, and so on are products of nature, not of factories. And the conditions required for developing these necessities are ideal for developing ourselves physically, mentally, and spiritually. What good is "progress" that robs us of sunshine, fresh air, and the vision of nature's beauty? Although advocates of industrial development bill agrarian life as primitive and backwards, the fact is that the relatively few people who realize significant profit from industrial enterprises build homes in the country, not atop the slag heaps on the south shore of Lake Michigan.

Unlike the wealth produced from industrial enterprises, nature's wealth is available to everyone. Any person (or, in industrial jargon, any "worker") can live comfortably, if simply, by cultivating a few acres of land and keeping a cow. The cow gives milk, from which we get butter, cheese, and a variety of other foods, while the bull or ox assists in producing food by plowing, hauling, and so on. Agricultural surpluses can be exchanged for other necessities, and thus agriculture and trade are the simple alternatives to industrial hell.

So what are the nation's unemployed steelworkers supposed to do? Trade their mortgaged homes for log cabins, their cars for horses, and their refrigerators for plows? Of course not. But the United States government, if it is at all concerned with the plight of working people, should introduce measures to gradually direct the nation toward an economy in which a larger percentage of the population obtains most of life's necessities directly from the land, an economy that enjoys a healthy independence from the products of the factory.

Critics of agrarian life point out that farming is hard work, with few vacations and with forced dependence on the weather. But compared to factory life, farm work is itself a vacation. And while the farmer depends on God to provide suitable weather, the factory worker must depend for his livelihood on the whims of his all-too-human employers. The sun rises and sets every day without fail, the seasons go their fairly predictable ways, and although there is the chance of drought and other natural disasters, God's creation, unlike man's industrial enterprises, never shuts down for good. Even with the disastrous droughts of the past few years, American farmers have produced enormous surpluses. In thevarnasrama system, one primary duty of the mercantile community, or of the government, is to distribute such surpluses to areas struck by drought, famine, and other disasters.

But if agrarian life is so simple and conducive to human well-being, why has almost everyone left the farm? Yes, they were driven away by combines and other machines that can do the work of hundreds of men. (And they continue to be driven away when they can no longer pay for the hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of factory-made equipment needed to run a modern, profit-oriented farm.) But most historians contend that the lure of city jobs, not the drudgery of farm life, was the prominent factor in taking people off the land. City jobs enabled workers to purchase the refrigerators, televisions, and washing machines that supposedly make life more enjoyable. People left the farms, in other words, to exchange a simple dependence on God for a quest after superficial bodily comforts.

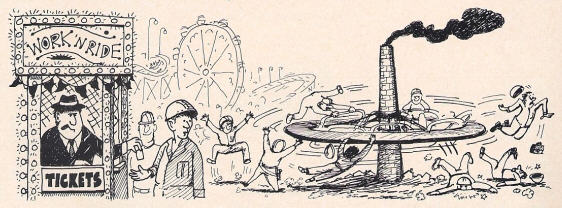

What do farmers, or "workers," do when they reach the city? They hire themselves out to manufacture or service or repair or sell the very amenities they came to enjoy. They build refrigerators, televisions, washing machines, automobiles, electric can openers, and so on, then go out and spend their paychecks on the same things. Sure they profit. Sure they earn more than they did back on the farm. How else could industrialists sell their wares? Not on the employees' labor alone are industrial fortunes built, but on the employees'patronage as well. Employers thrive by the invention, promotion, production, and sale of newer and newer amenities, while employees "thrive" by purchasing those amenities for their homes in Slag Valley and Irondale. Round and round the workers go, manufacturing and buying.

Does all this make life more enjoyable? No. Automobiles, washing machines, and fast-food restaurants are a bad trade for clean air, clean rivers, and fresh, unprocessed food. More essentially, a life directed toward artificially increasing bodily comforts is a bad trade for a simple life of depending on God. Not that the entire ingrown, exploitative, industrial cycle makes either employer or employee any less dependent on agriculture (ever eat a ball-bearing?), on nature (does U.S. Steel really manufacture steel?), or on God (can IBM make the sun rise?). It only makes us less conscious of that dependence.

Members of the Krsna consciousness movement are trying to make people more conscious of the Supreme Lord. A practical feature of their endeavors is the network of Krsna conscious farm communities, through which devotees intend to reestablish the varnasrama principles of social organization delineated in the Vedic literature. The basic principle of the varnasrama system is that the individuals who comprise society, as well as the various social divisions farmers, merchants, politicians, soldiers, educators, and so on cooperate to satisfy the Supreme Person. A society fully dedicated to God is fully protected by Him also, enjoying both social harmony and material prosperity. The more the farm-based varnasrama society expands, the less the workers of the world will be inclined to jump aboard the glittering and treacherous merry-go-round of industrial progress.