In the Vedic Tradition

The beginnings of New Talavan,

ISKCON's farming community in Southern Mississippi.

When Nico Kuyt was growing up, he lived in small towns in Canada and the northern United States. "I never lived on a farm, though," he recalls. "My father did engineering for big mining companies. But I always liked the woods, the country."

In 1968, while studying at the State University of New York (at Buffalo), Nico attended a philosophy course taught by Rupanuga dasa, a leader of the Hare Krsna movement. Rupanuga lectured from the Bhagavad-gita and hearing him, Nico became intrigued enough to visit the Buffalo Hare Krsna center a number of times.

During summer vacation, Nico went to Boulder, Colorado, to spend some time in the mountains. As the sun rose each morning over the Rocky Mountain peaks, he would meditate on the Hare Krsna mantra and study the Bhagavad-gita. I just wanted to see if there was anything to it," he says.

Apparently there was. When Nico returned to the East Coast, he joined the Hare Krsna movement in Buffalo and soon received the name Nityananda dasa. From Buffalo, Nityananda dasa traveled south to New Orleans, where he spent the next few years establishing a thriving Krsna conscious center,

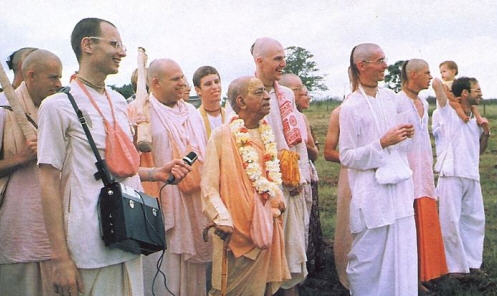

Then, in March 1974, Nityananda traveled to India for the yearly Hare Krsna International Festival, in Mayapur, West Bengal. (Mayapur is famous as the birthplace of the Hare Krsna movement. Five centuries ago, Lord Caitanya (an incarnation of Krsna) appeared there and taught everyone to chant the Hare Krsna mantra.)

Early each morning Srila Prabhupada, the founder and spiritual preceptor of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, would take a walk with some of his leading disciples and answer their questions about spiritual life and the practicalities of managing a worldwide society.

Using his 8mm movie camera as an excuse, Nityananda got permission to go along. As the group strolled on the bank of the Ganges in the predawn mists, he filmed them and listened intently to his spiritual master's words.

On these walks Srila Prabhupada told his disciples that he wanted to start farm projects all over the world. For many years the devotees had been trying to get people to accept the concepts of Krsna consciousness, as they appear in books likeBhagavad-gita. "But," Srila Prabhupada said, "if the people are in chaos, how will they be able to accept this great philosophy?" He told them that urban-industrial civilization left little scope for spiritual growth. Life in the country would be more favorable.

Beyond this, he pointed to the likelihood of a nuclear war that would clear away the mad civilization of cities and machines. Afterward, millions would be looking for a new way to live.

To Nityananda these ideas were a revelation. "Now we were to purchase land in the country and start farms! All of a sudden, I could see that we could bring the lost Vedic civilization back if we simply started Krsna conscious farming villages all over the countryside. People would live simply and peacefully again and cultivate spiritual awareness. My mind was running with excitement."

From Bengal to Mississippi

As soon as Nityananda got back from India, he began studying books on agriculture, animal husbandry, and village crafts. Then he decided to go out and find a piece of land. It wasn't easy. To the east, west, and south, New Orleans was bordered by swamps. To the north there was farmland, but it was too crowded. The only area left north of New Orleans was in southern Mississippi, around a town called Picayune.

On July 8, 1974, after much hunting, Nityananda signed the papers for a two-hundred-acre farm. "As we stood out in the yard watching the sun set behind the pine forests, we wondered what we were going to do next."

"At first we got off onto some side trips," he recalls. They went heavily into machinery and established a modern dairy, hoping to sell the milk commercially. "Before long we realized we were just increasing our headaches. We had come out to the farm to live simply, but we wound up worrying all the time about our big shiny red tractors, wagons, choppers, blowers, grinders, loaders, and unloaders.

At one point, I became very discouraged, Nityananda says. "Then I saw that I had to get a broader vision of what the farm was all about. I started meditating on what we were trying to accomplish."

Also, he consulted with other devotees who were developing farms in other parts of the country.

"But the biggest inspiration was Srila Prabhupada," he remembers. In March 1975, Srila Prabhupada was traveling through America, and Nityananda flew to Dallas to meet with him. Late one evening, he showed his spiritual master some 8mm films he'd taken at the farm. During the showing, Srila Prabhupada remained pensive and quiet, but afterward he eagerly questioned Nityananda about the farm and offered many practical suggestions.

"Srila Prabhupada emphasized the need for self-sufficiency," says Nityananda. "He said that we should obtain everything locally rather than from distant factories and cities. Srila Prabhupada wasn't looking toward the modern machine civilization for his ideas." Instead, he was taking them from India's ancient, agriculturally-based spiritual civilization (remnants of which still exist in Bengal and Orissa).

The novice farmers should grow their own grain, fruit, and vegetables, said Srila Prabhupada. They should keep cows for milk-which they could then turn into yogurt, butter, and curd. They should use oxen to plow the fields. They should grow sugar cane for sweetener. They should grow castor beans and use their oil to burn in lamps; that way they would be able to get along without electric lights. They should grow cotton, spin it into thread, and weave their own cloth on handlooms. For building materials they should use logs and bricks. "Become self-sufficient," Srila Prabhupada said again and again. "There is no need to go thirty or fifty miles to work." Finally, he encouraged Nityananda to build a magnificent temple as the center of the community. "Be patient, determined, and always enthusiastic," Srila Prabhupada told his disciple. "Be convinced of success; then Krsna will surely help you."

Later that year, in July, Srila Prabhupada visited the farm. "It's just like Bengal," he said, looking out over the fields. Earlier, Srila Prabhupada had spoken mainly of self-sufficiency, but now he gave Nityananda practical instructions about organizing the community. "Avoid machines. Keep everyone employed as a brahmana [priestly teacher], ksatriya [administrator], vaisya [farmer], or sudra (laborer]. Nobody should sit idle." He was explaining India's ancient social system, natural divisions that allow people to make the most of their special aptitudes and inclinations.

"The brahmanas," said Srila Prabhupada, "study transcendental literature, such as Bhagavad-gita and the Upanisads. And they lecture and instruct, as well as worship the Deity in the temple. They should have ideal character," he said, "and the other classes provide food and shelter out of appreciation for their guidance." The ksatriyas, taking advice from the brahmanas, manage and govern the village; also, they apportion land to the vaisyas. The vaisyas use the land to produce grains, fruits, and vegetables and to raise cows for milk. They give twenty-five percent of their produce or earnings to the ksatriyas, who spend it for village projects. The sudras, the artisans and craftsmen, assist the other three classes.

"This is an ideal society,'' Srila Prabhupada affirmed. To begin with, everyone works in an area that perfectly Suits his psychophysical nature. If someone likes intellectual activities, he works as a brahmana. If someone likes managing and organizing, he works as a ksatriya. If someone likes business and agriculture, he works as a vaisya. And if someone likes the arts and crafts, he works as a sudra.

All four classes are needed. Like the human body, the social body requires a brain (the brahman, as) to give guidance, arms (the ksatriyas) to organize and defend, a stomach (the vaisyas) to produce energy, and legs (the sudras) to offer support. When all four classes cooperate, everyone is employed and the society runs smoothly.

Closer to Self-sufficiency

"We are not against machines, "Srila Prabhupada told Nityananda as they walked around the farm. "If we can use machines, that is good-but not at the risk of keeping men unemployed. These modern administrators are rascals-they do not realize that by using so many machines they are keeping millions of men unemployed. And the welfare department is paying them. The government is paying them to become hippies, criminals, and prostitutes. A boy keeps a girl friend; the girl is getting welfare; and he is using the money to buy drugs."

"It was obvious he wasn't talking about some vague, theoretical philosophy," says Nityananda. "He was showing us that we could take the insights of the Vedic culture and put them to practical use on this farm in southern Mississippi. After that visit, my vision for developing the farm became strong and clear."

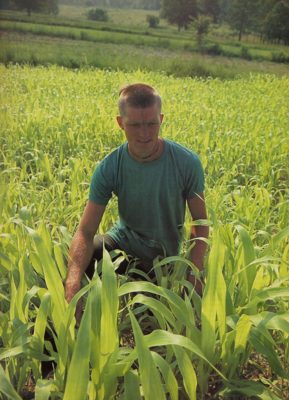

Right after Srila Prabhupada left, Nityananda started getting rid of most of the machines. And now, three years later, he's brought the farm many steps closer to the goal of self-sufficiency. "For heat and hot water we use wood stoves," he says. "We cut oak and pine in our woodlands. We're growing our own vegetables. Last summer we had more eggplants than we could eat and good crops of potatoes, spinach, and squash. We have lots of pecan trees. We produce all our own milk, butter, and yogurt-we haven't bought any in five years, and usually we have enough extra to send to the temple in New Orleans. We grow all our own hay for the cows, and we milk them by hand. We're not dependent on milking machines; that's another step we've taken.

"We don't buy any chemical fertilizers, herbicides, or insecticides," he continues. "All our farming is completely natural. For fertilizer we use cow manure. Instead of putting up barbed wire fences, we plant thorny hedges. We wash all our clothes by hand. We still have an electric pump for our well, but this year we'll replace it with a windmill.

"We'll gladly give two to five acres to families who will use it for growing crops or carrying on a craft or trade," Nityananda adds. "And we'll give them free materials and help them build a house. We have a first-rate school for the children, and the parents can come to the temple and learn about the science of self-realization.

"We're getting ready for the day when thousands of people will come here," he says. "Civilization as we know it will be finished some day soon-by economic disaster or war. People won't be listening to their former leaders; they'll be looking for a better way to live. And when that happens, we'll be ready with Krsna conscious farming villages like this one."