Food, education, employment, and devotion —

all one needs to have a successful material and spiritual life —

have become a reality in this remote village

“If the village perishes, India will perish too. India will be no more India.” —M. K. Gandhi

Can you imagine an India where everyone has enough food to eat, pure water to drink, and clean air to breathe; where no one has to travel long distances to earn their daily bread; where people have enough time to relax and enjoy and at the same time live a sublime life of purpose, meaning and fulfillment? In the middle of cutthroat competition where survival seems impossible, it is hard to imagine such a situation. Even in villages, where life is relatively simple, such a situation has become a dream.

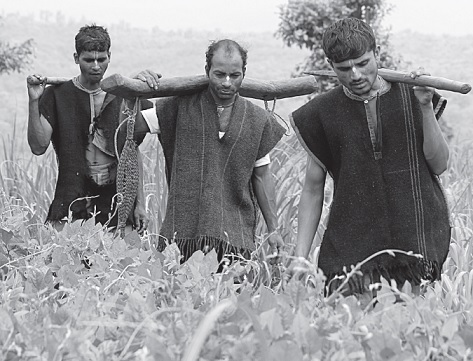

His Holiness Bhakti Rasamrita Swami Maharaja (center), Rupa Vilasa

Dasa (extreme left) and other members of Venu-Madhuri team

More than half the population of the world now lives in urban areas, and more people continue to move from villages to cities. With many industries providing employment in the metropolises, more and more people are allured to move out of the villages seeking a better life. And with the mechanization of agriculture, farming has become uneconomical.

Urbanization is seen as modern and progressive, whereas living in a simple village is considered unfashionable and primitive. But urbanization is not without problems. Global warming, pollution of the environment, rising poverty levels, are just a few. Scientists and philosophers are sending apocalyptic warnings. People are slowly realizing that if humanity does not give up the unsustainable lifestyle of living in a city, great calamities are likely to hit us and our planet will soon become uninhabitable.

Srila Prabhupada had envisioned this long ago. He would urge his followers to follow the principle of “Simple Living, High Thinking.” He had said, “As far as possible try to adjust to a natural way of life, free from dependence on machines” (Letter to Subhavilasa, Mayapur 16 March, 1977). If villagers had a fruitful, viable alternative in their own villages and were assisted through sustained rural development, they would not even think of migration to larger cities. At the same time, if they were inspired to take up Krishna consciousness and practice spiritual life, their lives would become happy and sublime.

Venu-Madhuri: The Seed and the Need

What began as a desire to fulfill Srila Prabhupada’s vision soon took the shape and form of Venu- Madhuri, a project conceived by senior ISKCON leader His Holiness Bhakti Rasamrita Swami Maharaja. Rupa Vilasa Dasa, a postgraduate in environmental science, joined him along with a few other devotees. Soon they laid out the vision and mission of this trust. Unlike other ISKCON farm projects where a city temple purchases a plot of land in the countryside and its members practice agriculture and cow protection, this project would be different. It would encourage and empower local villagers to adopt traditional time-tested practices of agriculture and animal husbandry. In this way, their occupation becomes economically feasible and even profitable. By cooperating and helping each other, a village can become selfsufficient in all the basic needs, thus reducing their dependence on city supplies to the minimum.

When I visited Kolhapur last October, Rupa Vilasa kindly agreed to take me to Ramanwadi, the actual site of Venu-Madhuri project. A small village of less than 100 houses in Kolhapur, Maharashtra, it is situated on the Sahyadri mountain ranges, or the Western ghats. Despite the heavy rainfall the region receives, the village used to face severe water crisis during summer. Barely 2.5 acres of land were under perennial irrigation. Apart from the four months of the rainy season when they grew paddy and finger millet, the villagers depended on the forests for livelihood by selling honey, fuel and timber to the city industries. They hardly realized how the forest was their shelter and how deforestation was depriving them of their basic necessities. After the rainy season, the farmers would move to Ichalkaranji, 95 kms away, to work in hellish power looms. Yashwant Patil, a former worker in this industry, recalls his terrible experience: “I was always treated as a bonded labor, because they knew I had no other alternative. Financial loans forced me to work extra hours, even at the cost of my health. I somehow tolerated the abuse for thirteen years.”

Local

villagers

coming together

to construct the

mud-check

dam

Social evils were on the rise. Family discords, abuse of women, and alcoholic addictions were not uncommon. Poor education and lack of proper medical facilities were other issues. Pregnant ladies would have to travel by bullock cart to come down the hill, and often they would deliver the child before they could reach the hospital, thus causing fatal injuries to both the mother and the baby.

Ramanwadi is not unique with such cases. Thousands of villages all over India are facing similar problems. The government’s apathy toward rural development and its overemphasis toward industrialization have encouraged greedy capitalists to exploit cheap labor found in villages. The gap between the rich and the poor is deeply widening, putting millions into poverty. Venu-Madhuri project was developed with a view to improving the condition of such Indian villagers, who are mere helpless spectators of an unsustainable civilization.

The project outlined its purpose:

• Work with existing villages to make a model village aimed towards self-sufficiency

• Promote sustainable development through traditional Vedic wisdom

• Share the message and practices of Krishna consciousness with the villagers and make their lives happy and sublime.

Construction of

the irrigation

pipe-line

Tasting the First Success

After studying the condition of the village and the people, the Venu-Madhuri team concluded that water supply and management was the most important issue they need to address. In May 2003, it got together all villagers and rallied for months to contribute money and free labor. Finally they constructed a 40-feet long and 15-feet high mud-check dam using locally available construction material. Although their efforts faced a setback during the first monsoon, when the dam got partially washed away due to the force of water, the villagers came together and repaired the dam.

Children from the local

village school

In March 2004, they started work on irrigation. An underground perennial stream was tapped and the water was channeled through a three-inch PVC pipe, 2,700 feet long. Traditional village techniques enabled the channeling of water from a high elevation to low-lying fields using gravity. Use of PVC pipes avoided losses due to percolation and evaporation.

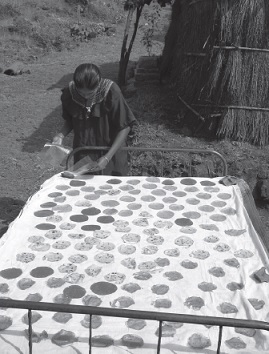

A woman making papad

The villagers contributed 50% of the total cost by contributing money, free labor, and grains. Eleven acres of wasteland came under perennial irrigation, and the villagers got back their investment within the first three months.

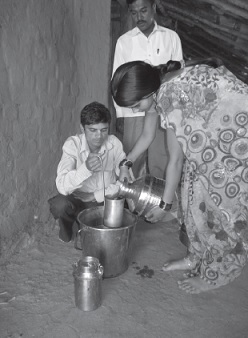

Construction of mudstoves

In December 2006, work started on the final phase of the project. A 9,500-foot PVC pipeline, four inches in diameter, was laid to transport water from a perennial stream. This time the villagers faced a daunting task, given the challenges posed by the natural terrain. The pipe had to be laid through streams, valleys and extremely uneven land so that the entire water distribution is carried using earth’s gravity alone, without electricity. Again the villagers contributed with money, free labor and grain. In this second phase, thirty-seven acres of land came under perennial irrigation. Because there is no electrical consumption, the two phases of project together conserve about 69,120 units of electricity every year.

Farmers have started employing

bulls for tilling the land

This entire project created a revolutionary change in the economy of the region. In 2004, the village sugarcane production here was 75 tonnes. By 2012, it increased to 1000 tonnes, selling at 2500 rupees per tonne. Labor worth Rs. 2,25,000 is now generated annually in the village through sugarcane harvest. The villagers also now grow oilseeds, vegetables, and millets for personal consumption and surplus products are sold in the market.

Green Farming and Energy Conservation

Indian farmers, especially those in Maharashtra, have suffered the most due to extravagant promises made by agribusiness giants. Understanding the need for safe agricultural practices, Venu-Madhuri team ran frequent education drives about the harmful effects of chemical farming and the use of insecticides and pesticides. By adopting the use of cow dung, cow urine, vermicompost, and the traditional bija-samskara, more than fifteen farmers have started shifting to organic farming. Over thirty-five vermicomposting units and more than 1200 horticultural plants were distributed among fifty-five families. They even started collaborating with other non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to learn about the best practices in farming and agriculture. Rupa Vilasa has initiated an allfarmer gathering in Kolhapur where they discuss common grievances and challenges that the villagers face and how to implement the best possible solution.

Ghani yoked to a bull for making oil

A major cause of health disorders in villages, especially among women and children, is indoor air pollution (IAP), caused due to firewood and agro-waste. According to World Health Organization, over 500,000 women and children in rural India die prematurely every year due to diseases linked to long term exposure to IAP. The Venu- Madhuri team offered to introduce biogas as an alternative fuel. But first they needed to get enough number of cows and bulls.

Villagers celebrating Bendur,

a festival centered on bulls

Villagers stopped abandoning their cows and started getting them back from the forests. Three village youths pledged cow protection. A full-time veterinary doctor volunteered to provide medical care for all the animals. Using derivatives like cow dung and urine, villagers started producing tooth powder, distilled cow urine, cow dung dhoop (used for religious worship) thus earning a decent livelihood. Overall the villagers realized the great economic value of cow protection and decided to care for them just as their own family members.

With increasing number of cows coming under care, the villagers started utilizing cow dung for producing biogas. Venu-Madhuri supplied a biogas plant each to 23 families. Biogas production automatically eliminated the need to cut down forest trees for fuel. Household women and children no longer had to inhale hazardous smoke in kitchen as IAP had gone down. Deforestation reduced by a significant level: 113 tonnes of firewood, or roughly 900–1000 full grown trees of around 20 years age, are conserved annually. In terms of reducing air pollution, 206.8 tonnes of carbon-dioxide gas are prevented from getting released to the atmosphere.

Rupa Vilasa explains, “Saving cows is a crucial factor in socioeconomical and cultural lif e. Cow yields milk, urine and manure dung, all of which have tremendous medicinal importance. The bull is a mini-tractor that works without diesel. This is the secret of sustainability. Cows produce cows while tractors produce debts that lead to suicides. In 2001, Ramanwadi villagers had 12 cattle; today we have more than 90. We have a special breed of bull, the Dangi breed; his job is to procreate only. As a result, all the future cows are healthy. The villagers have also restarted the traditional festival, known as Bendur, centered on worship of bulls.”

Towards Self-sufficiency

The Venu-Madhuri team along with Ramanwadi villagers has revived the traditional ghani system for producing oil from oilseeds. Ghani is a cylindrical pit made of either stone or wood that holds oilseeds. A heavy upright pestle kept in the center is yoked to a bull. As the animal moves in a circular ambit, the pestle rotates, exerting lateral pressure on the upper chest of the pit, first pulverizing the oilseed and then crushing. out its oil. The machine is also used for producing oilcakes that are used to feed cattle. Another bull-driven machine is used to produce wheat flour.

Dairy selling cow urine

Today a cow urine dairy sells cow urine at Rs. 5/liter — a good source of income. Production of organic jaggery and cow derivatives has increased. All these benefits have stopped migration of many villagers to the cities, and even reversed the migration back to the village. They prefer to work in the village and spend more time with their family than spend torturous hours toiling in mechanized industries, separated from their beloved ones.

Yuvraj Patil, a Ramanwadi resident, says, “My family had just two buffaloes in 2001, and to sell its milk we had to go up and down the hill every day — a distance of 8-10 kms. We could preserve just about 400 ml of milk for our personal consumption. Today, we have six cows and eight bulls. We have ample milk for consumption and we distribute free buttermilk to our neighbors. Firewood use has fallen to almost nil after we started using biogas. Because of these increased savings, I could spend Rs. 24000 to convert half acre of land into cultivable land. We even have a small mud house, built with our own hands.”

Cow-based derivatives like soap

and tooth powder

Other initiatives that have added to the economic development of the locals are:

• Special training in handloom art

• Bamboo-stripping

• Teaching village women on making papad and cloth bags, that are sold in cities

• Imparting the knowledge of house building

• Routine health checkups, where villagers are made aware of the need to follow proper hygiene and dietary regulations.

Keeping Krishna in the Center

Besides helping the villagers economically and in attaining selfsufficiency, Venu-Madhuri also focuses on the overall spiritual growth of every individual. Under a charming village-style temple for their Lordships Sri Sri Radha-Krishna , villagers come together to participate in various devotional programs that constitute prayers, lectures, and services. Weekly satsanga programs and annual Vaishnava festivals are regularly held. On Ekadasi days, everyone comes together in the evening for long hours of kirtana. Annamrita, a Venu-Madhuri initiative, provides free, nutritious and sumptuous meals (Krishna -prasada) for the village schoolchildren.

The results of such spiritual programs have been incredible. Many caste-based groups have dissolved, thus creating an atmosphere of unity and love. Animal slaughter during social festivals has completely stopped. Putting aside all their sectarian differences, people come together for marriages and other social events and serve each other with affection. The unity among them was recently visible when all of them unanimously chose one of their members and elected him as the sarpanch (village head), avoiding the tedious and often bitter election process.

Ever since these programs have started in Ramanwadi, many villagers have become serious practitioners of Krishna consciousness. Daily chanting sixteen rounds of the Hare Krishna mantra and following the four regulative principles, some have even accepted spiritual initiation. Some village youngsters have moved to the ISKCON center in Kolhapur to undergo more intense training in Vaishnava practices and lifestyle.

Awards, Recognitions, and Acknowledgments

The journey so far has been a long one, fraught with many challenges. But it has been extremely sweet at the same time. Recognizing its extraordinary efforts in environmental preservation and social welfare, Maharashtra Energy Development Agency (MEDA) bestowed Venu- Madhuri with the sixth state-level award for excellence in energy conservation and management. Venu-Madhuri’s members have given presentations at the National Institute of Rural Development (NIRD) and National Workshop at Hyderabad. International acclaim came when it was honored at Permaculture course conducted by Global Eco-village Networking of Australia at Sri Lanka.

Several leading newspapers and magazines have published articles and reports on Venu-Madhuri. Leading yoga guru Baba Ramdev appreciated it for its cow-centered rural development.

Venu-Madhuri is a source of inspiration for many, who consider this project as a model that can be replicated in other villages of India. Srila Prabhupada’s vision of holistic development of Indian villages has come to life at least here in Ramanwadi, and by his grace many more villages are due to follow suit.

Mukundamala Dasa is a member of BTG India editorial team.