Frustration gives way to illumination during one extraordinary night in the life of a prostitute

While prostitutes are often depicted negatively in traditional literature, some religious texts depict them positively as testimonies to the transformational potency of divine grace. Thus, in the Gospel is found a story of a prostitute (considered by some to be Mary Magdalene) who was redeemed by Jesus. In Gaudiya Vaisnava literature such as the Caitanya-caritamrta comes the story of the saint Haridasa Thakura, who delivered a prostitute who had been commissioned to orchestrate his fall.

Prostitutes as Teachers

While such narratives that depict prostitutes as receivers of wisdom are not uncommon, far less common are narratives that depict them as teachers of wisdom. In the Vaisnava tradition, we find one such tale in the life of the medieval saint Bilvamangala Thakura. In his pre-saintly life, he was attached to a prostitute named Cintamani, who was almost like his mistress. Once he braved a fierce storm, a dark night and a flooding river to get to her place. When she saw how much trouble he had gone through to reach her, she exclaimed, “If you had gone through that much trouble to reach God, you would have become a saint.” Those words struck Bilvamangala harder than could have any of the thunderbolts of that stormy night – they jolted his spiritual intelligence out of slumber. He thanked her, renounced the world and left for Vrindavan, where he went on to become one of the most celebrated saintly poets in the Vaisnava tradition.

Bilvamangala’s narrative features a prostitute speaking one devotional exhortation, but a narrative in the Srimad – Bhagavatam features a prostitute singing a song filled with several philosophical insights. This song occurs in the eighth chapter of the eleventh canto of the Bhagavatam in its section called the Uddhava- Gita (which extends from chapters six to twenty-nine), which is Krishna's instruction to Uddhava. Within the Uddhava Gita comes a section known as the Bhiksu-gita, the song of the renunciate. Though some consider this renunciate to be Dattatreya, an incarnation of the Lord, the Bhagavatam refers to him simply by his social designation as the brahmana or as an avadhuta (one who has transcended normal social conventions). In the Bhiksu-gita, this saint instructs King Yadu about the truths of life by sharing what he has learnt from his twenty-four gurus. One such guru is a prostitute named Pingala.

Gurus who Teach Without Teaching

The Bhiksu-gita offers a conception of guru different from the standard conception of a wise instructing teacher. An instructing guru is essential for a seeker’s spiritual growth and the Bhagavatam is filled with narratives of such gurus instructing seekers about the truths of life. But the Bhagavatam in the Bhiksu-gita shifts the onus of learning from the teacher to the seeker. When the onus for effective knowledge transfer is on the guru, seekers may become passive, thinking that transmitting scriptural knowledge in a way that they can internalize is the guru’s responsibility. To avoid such passivity among seekers, this Bhagavatam section conveys that they need to take the responsibility for internalizing scriptural knowledge. How? If seekers observe the world keenly, they can see the truths of life demonstrated through the happenings in the world. Those things in the world that demonstrate life’s truths can also be considered to be gurus, for they reiterate and reinforce the guru’s teachings. The Bhiksu-gita uses the word guru in this nuanced and expanded sense.

The Bhagavatam doesn’t describe, or even hint at, any interaction between the brahmana and Pingala. In fact, the brahmana doesn’t receive verbal instruction from, or even directly interact with, any of his twenty-gurus, yet they act as sources of spiritual edification for him. All the lessons he learns from them are inferences he draws by observing them. When he describes any event from which he learnt something valuable, he narrates that event in the voice of an omniscient narrator. It could be said that he just happened to be at the right place at the right time, but there’s more to it. He also had the right disposition – a relentless zeal to learn that enabled him to observe the right thing and draw the right lesson. He learns from Pingala the power of detachment: it enables one to attain peace and happiness (11.08.27) acts as a sword that frees one from the tormenting shackles of desires (28).

The Prostitute’s Frustration

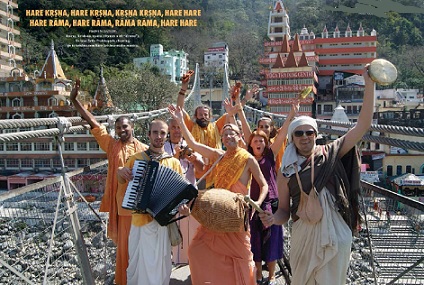

Pingala’s story begins (22) with what would be a prostitute’s typical daily, or more precisely nightly, routine. As the evening sets in, Pingala dresses and decorates herself seductively (23: bibhrati rupam uttamam) and steps out of her house to attract one of the many men who are going along the road. Like any other woman in her profession, she is looking for a wealthy man who will pay her charges (24: sulka-dan vittavataù) and maybe even give something extra if he turns out to be generous (25: bhuri-dau). Yet she is looking for more – she hopes to get not just a customer, but a lover who will give her affection and pleasure. The Bhagavatam states – and she herself mentions repeatedly in her song, which we will duly come to – that she was looking for a lover (kantau). Evening turns to night and night to midnight, yet no one approaches her. Perplexed and disappointed and exhausted, she returns to her room to nap, but wakes up with a start and rushes out, fearing that she might miss a customer. Trying desperately to attract someone, she goes further down the street, but to no avail. As her hopes of earning on that night dry, her face falls and – wonder of wonder – she has a Eureka moment. The Bhagavatam (27) states that a great sense of detachment awakes within her (nirvedau paramo jaje). This detachment not only removes her anxiety, but also replaces it with happiness (cinta-hetuh sukhavahah). She analyzes and verbalizes her epiphany in the form of a celebrated song that is sometimes sung to musical accompaniment, as are other better known songs from the Bhagavatam such as the Gopi-gita.

Pingala’s Song

She begins (30) by observing herself from a perspective outside of herself, lamenting at the extent to which she had fallen into illusion because of her uncontrolled mind. Sometimes we get carried away by our mind and under its spell, we do something undesirable for quite some time till we suddenly come out of the stupor and are shocked to see how far we have gone from where we wanted to go. Coming to a similar sudden self-awareness, Pingala laments her folly in seeking worthless lovers (asatam kamal).

Why she considers her lovers worthless is revealed in the next verse (31), where she contrasts them with the Lord who resides right in her own heart and who grants the supreme wealth and the ultimate pleasure. As compared to the one who is waiting to be her eternal lover, all worldly lovers are insignificant.

In the next verse (32), she laments that, instead of striving to please such a wonderful Lord, she has struggled in vain to please those who are themselves tormented by lust and greed, and are therefore pitiable. Thus she further contrasts them with the Lord whom she has previously referred to as the reservoir and provider of happiness (31: ramanam rati-pradam). She laments that she has futilely tormented herself by taking up the regrettable profession of a prostitute (sanketya-vatti). In his commentary, Bhaktisiddhanta Sarasvati Thakura elaborates that sanketya-vatti refers more specifically to the vocation of using one’s body to make gestures (sanketa) that arouse people sexually. What Pingala recognizes to be a regrettable profession is today a super-lucrative profession with the pornographic industry’s revenues exceeding the combined revenues of all professional football, baseball and basketball franchises.

After thus discerning the worthlessness of her lovers, she then analyzes (33) the worthlessness of the other component in her pursuit of pleasure: her beautiful body. Comparing the body unflatteringly to a house with bones as its beams, she ascribes its beauty to the cover-up job done by layers of skin, hair and nails – things that women beautify in various ways. Yet no cover-up job is perfect; what is covered up comes up in someway or the other. All bodies, including the most beautiful ones, ooze out sweat, urine and stool, forcefully reminding us that the skin-deep beauty doesn’t always stay even that deep – the illusoriness of bodily beauty becomes apparent periodically even at the level of the skin.

Having thus analyzed the futility of seeking pleasure through the body and those who would love the body, she returns (34) to lamenting her folly in pursuing such lovers instead of the supreme lover, the infallible Lord (acyuta) who would have granted her an eternally beautiful spiritual form (atma-dat).

Glorifying the Lord with a flurry of epithets – He is her well-wisher, lover, master and indwelling companion – she then resolves (35) to attain Him by offering herself to him. Adopting as her model the Goddess of Fortune, who offers herself to the Lord and delights with him, Pingala resolves to similarly surrender to the Lord and thus “purchase” (vikriya) Him. Her usage of monetary language harkens back to her earlier hope of purchasing lovers by selling her body. It also points to the inclusiveness of bhakti, which asks us to not renounce worldly things, but to use them in the Lord’s service. We can use our body and our bodily talents, appropriately adjusted, in the service of the Lord.

Lest any attraction still remain in her heart for worldly lovers, she rejects (36) them by asking rhetorically that even the best of them, to the level of gods, are temporary – what pleasure can they offer to their wives?

As she senses her unexpected and unexpectedly strong detachment, she contemplates where it has come from. She infers (37) that the source could be only one – Lord Visnu, who is somehow pleased with her. Exhibiting laudable humility, she doesn’t take the credit for her change of heart, but instead gives credit to the Lord.

She then reflects (38) on that which had earlier seemed to be a misfortune – the absence of any customer to fulfill her desire. Thanks to her spiritual awakening, she now sees that her misery was not due to frustration of desire, but due to domination by desire. Here’s an example to understand this.

Suppose a desire for alcohol drives a recovering alcoholic out of bed in the middle of the night. He drives to a nearby bar, but finds that its alcohol stock is over. He feels miserable and attributes his misery to the frustration of his desire for alcohol. But suppose he suddenly gets an epiphany: “While others are sleeping peacefully in their beds, I am wandering around at night, dragged out of bed and halfway across the town at an unearthly hour. Why? Because the desire for alcohol is dominating me.” As he understands how desire has enslaved him, a deep detachment develops within him – the craving for a drink suddenly disappears from his mind. The end of that torturous craving makes him peaceful, just as, say, the end of a nagging back-pain makes a patient peaceful.

With this example, we can understand when Pingala says that misery is not misfortune if it awakens detachment, because that detachment brings great peace (samam acchati).

Feeling convinced that her sense of detachment is indeed a favor bestowed by the Lord, she resolves (39) to gratefully treasure this detachment firstly by avoiding materialistic situations and desires, and secondly by seeking the shelter of the Lord. Her resolve to stay away from materialistic stimuli is a necessary precaution, similar to the resolve of recovering alcoholics to stay away from bars – they know that they are always just “one drink away from relapse.”

Her next verse (40) conveys how she plans to take the Lord’s shelter: she will stay satisfied materially with whatever she gets by honorable means (yatha-labhena jivati) and she will seek pleasure nowhere else except at the spiritual level in the Lord who is the reservoir of pleasure (atmana ramanena vai).

In the next verse (41), she metaphorically conveys the predicament that bedevils all of us – we have fallen in a dark well (samsara-kupe patitam), which represents material existence wherein we fall to ignorant material consciousness from the ground level of spiritual consciousness that is normal to us as souls. Worse still, we have been blinded by sense objects (visayair musiteksanam), which rivet our consciousness to the material level of reality and make us oblivious to the spiritual level. Worst of all, we have been caught by the serpent of time that is pulling us into its belly with each passing moment. She concludes this grim depiction by asking rhetorically: “Who other than the Lord can rescue us?” The bhakti tradition often expands the well metaphor by depicting the Lord as the rescuer outside the well who throws a rope for us. And the rope is the process of bhakti-yoga that elevates our consciousness from the material level to the spiritual level.

In the last verse of her song (42), she again uses the time-as-serpent metaphor, expanding its ambit from the individual to the whole world, which being perishable is on the verge of being devoured by the serpent. She declares that only when we see the temporariness of the whole material existence and become detached from it can we become our own protectors. That is, only by such a vision will we place ourselves firmly under the Lord’s protection. Going back to the well metaphor, only when we are convinced that the well is a dreadful place will we hold the rope firmly, that is, practice bhakti determinedly. To the extent we stay in the Lord’s protection, to that extent we become our own protectors.

From Life-negating Desire to Life-affirming Desire

Pingala’s narrative ends on a note that might seem anticlimactic – she peacefully sits down on her bed and happily goes to sleep. This is such an ordinary activity that we might miss its significance here. For a prostitute to not get a single customer throughout the night is as bad as for a shopkeeper to not get a single customer throughout the day. The shopkeeper would be irritated, worried, frustrated — and may well lose night sleep over it. The fact that Pingala after a night of zero business could sleep happily indicates that her detachment was for real.

Her story ends here; we are given no post-script. That is understandable, for the brahmana narrator is not sketching life-stories, but is drawing life lessons. Accordingly, he concludes this narration (44) by reiterating the lesson he learnt from it, a lesson that will resonate with anyone who has been addicted to anything: “Desire is the cause of misery; freedom from desire is the cause of happiness.”

Lest this concluding message of abandoning desire sound lifenegating, we need to remember that the Bhagavatam’s central message is not eradication of desire, but its redirection from matter to Bhagavan, who is the eponym and central purpose of the whole book. Reflecting this spirit of positive redirection, Pingala herself desires (36) to lovingly serve the Lord and delight eternally therein. And desiring to love and serve Krishna is eminently life-affirming. Such spiritual desires grant us access to devotional happiness in this very life. And they also fulfill our longing for a life uninterrupted by distress and death by propelling us to the Lord’s eternal abode that is free from anxiety (Vaikuntha).

Worldly desire or desire divorced from Krishna is life-negating because it drags us away from he who is the pivot of eternal ecstatic life. Pingala’s narrative, by concluding with a call to reject such desires, sets the scene for a life animated by fulfilling spiritual desires.

Caitanya Carana Dasa is the associate-editor of Back to Godhead (US and Indian editions). To subscribe for his daily Bhagavad-gita reflections, please subscribe for Gitadaily on his website, thespiritualscientist.com.