1. Within every adversity is an opportunity – the universe is a university

The Bhagavad-gita begins with the famed warrior Arjuna about to participate in a war that will annihilate his entire clan. Thinking about the upcoming fratricide, he suffers an emotional breakdown. He attempts earnestly to reason his way out, but emotion trumps reason in the inner battle. In despair, he turns to Krishna : “Help!”

Krishna , by His presence and presentation, lifts Arjuna out of both the outer and the inner battlefields. The supreme teacher takes His student to magnificent summits of wisdom that the world has rarely scaled before or after. When they return to the battlefield at the end of the Gita, Arjuna is intellectually illumined, spiritually strengthened and emotionally enlivened.

By thus transforming a battlefield into a classroom, Krishna demonstrates that He can utilize every circumstance as a setting for education. And the wisdom he has provided through the Gita can enable us to similarly redefine the various battle-like situations that confront us in our daily life. If we accept Krishna as our teacher by meditating on the Gita, he will use the unlikeliest of settings to impart the most unforgettable of lessons. And our life-journey will transform into an adventure in ever-increasing wisdom.

In fact, Gita wisdom explains that the world we live in is an arena for our spiritual evolution. The universe is essentially a university. Every moment is an opportunity to grow in wisdom and love.

2. Be concerned, not disturbed, by change – the real you is indestructible

The world around us is subject to constant change, change that is often unstoppable, uncontrollable and unpredictable. Such change makes us stressed and worried; we naturally look for something unchanging for security. The Bhagavad-gita explains that such an unchanging reality lies within us. We ourselves are at our core souls, spiritual beings who are indestructible (2.13). None of the weapons that can destroy our body and other material things can even scratch the spiritual soul (2.22). No external change, however threatening or devastating it may seem, can harm our essence. Understanding this fills us with a profound peace that equips us to respond maturely to external changes.

As we live and act in the world, we do need to be concerned about external changes. Due concern about them helps us to think calmly and respond intelligently. But if we become unduly excited, then our consciousness gets caught up in externals and we get attached to them. Thereafter, when things start going wrong, our attachments don’t let us withdraw our consciousness from external things and so we suffer. To the extent we rejoice when external things go right, to that extent we will be forced to lament when those things go wrong.

That’s why the Gita (2.15) recommends that we avoid becoming disproportionately delighted by pleasure or dejected by pain, and thus keep growing spiritually amidst external changes.

3. Spirituality is the culmination of science – become a spiritual scientist

Science progresses by first assuming on faith that nature has an underlying order and then seeking to discover that order. Newton discovered gravity not merely by observing the falling fruit, but by his faith that a rational order in nature had caused the fruit to fall. Noted physicist Paul Davies acknowledges, “Even the most atheistic scientist accepts as an act of faith the existence of a law-like order in nature.”

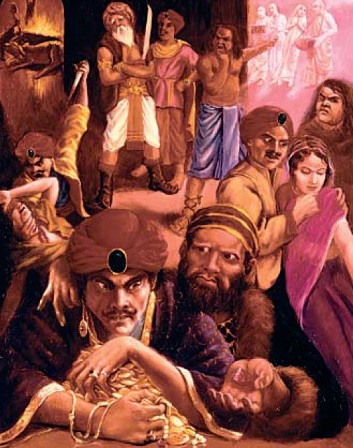

Lust, anger and greed — the three parasites in the mind

Gita wisdom takes this scientific faith to its next level by pointing to the person behind the order. Many eminent scientists hold such an inference to be not just reasonable but essential. Why? Because the more science fathoms the laws of nature, the more their intricacy and inter-relationship insists that they couldn’t have come by chance. Reputed Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan put it well, “An equation for me has no meaning, unless it represents a thought of God.” That God who governs nature, the Bhagavad-gita (9.10) reveals, is Krishna .

Acknowledging the divine brings meaning not just to the natural order, but also to human affairs. The Gita (15.15) indicates that the same God who oversees insentient matter also guides our consciousness towards its ultimate unfolding.

To facilitate our spiritual evolution, the Gita offers a time-honored methodology of yoga that offers enterprising spiritual scientists experiential perception of higher spiritual realities. Just as science confirms its theories through experiments, spirituality confirms its tenets through experiences.

Discovering the order that encompasses all of existence – matter and consciousness – is the culmination of science.

4. Don’t let desires become parasites – be restrained to avoid becoming drained

Our desires can energize us, but if they are not regulated they act like parasites and exhaust us. The Bhagavad-gita (16.21–22) indicates that such desires that impel us to self-defeating actions fall into three broad categories: lust, anger and greed. Lust and greed often fuel our desires for the many worldly objects that enter our vision and imagination, be they glitzy forms or gaudy products. These desires are innumerable and endless, and most of them are unrealistic that cannot be fulfilled. Consequently, a conscious or subconscious irritation builds up within us. When this irritation becomes intolerable, we succumb to anger, which perverts us into becoming sulky (mentally angry) or snappy (verbally angry) or even beastly (physically angry). In this way, lust, greed and anger cumulatively divert our focus away from the main goals of our life, both material and spiritual. The resulting inattentiveness makes us falter and blunder during the course of our life. As our plans misfire and backfire, and nothing seems to be working, we get mentally exhausted and exasperated. Just as parasites drain their host, so do such desires drain us.

That’s why it is prudent to be restrained. Being restrained doesn’t mean sentencing ourselves to a life of dry denial; it simply means choosing our desires judiciously and not letting the world foist desires on us. By introspection we can shortlist those of our desires that grow from our core; that reflect our aspirations and talents; that propel us towards self-actualization.

5. Look at the mind before you look with the mind

When a normally cordial friend snaps at us for no reason, we understand sympathetically, “That’s due to a bad mood.” We then ascribe their irritability to their moody mind, thereby separating their mind from them.

Differentiating between the mind with its moods and the person is something that we do not just with others but also with ourselves. However, with ourselves we usually do it after the event to rationalize it: “I spoke like that because I was in a foul mood.” If instead we could catch our bad moods beforehand, we could avoid much trouble.

Pertinently, the Bhagavad-gita (14.22) urges us to first observe our emotions and then decide whether to act on them. This essentially involves looking at the mind instead of looking with the mind. Looking with the mind means identifying ourselves with the mood of the mind and acting on it. It means using the mind as our spectacles and letting its color tinge our vision.

Looking at the mind means looking first at the specs – it means becoming aware of our feelings and evaluating: “Are these my authentic emotions coming from my core values and central concerns? Or are these just passing fancies, kneejerk reactions to extraneous events, hormonal rushes that have little to do with the essential me?”

By becoming introspective, we can become selective about which emotions we act on and thus become much more constructively productive.

Caitanya Carana Dasa is the associate-editor of Back to Godhead (US and Indian editions). To subscribe for his daily Bhagavad-gita reflections, please subscribe for Gitadaily on his website, thespiritualscientist.com.