We often think that bad habits are insurmountable, but this is not true.

The article is based on a talk given by the author at the University of Queensland in Australia, on March 18, 2016.

We can study the nature of habits using the acronym H-A-B-I-T: Hardness, Affliction, Blitz, Introspection, Transformation.

H: Hardness

We are the products of our habits – and we are their producers too. In this dual power of habits lies the cause of our bondage and the key to our freedom. When we do something repeatedly, such repetition reinforces our inclination for doing that action till it becomes our default course of action. That is, it becomes a habit. Certainly, many habits can be good, and they can help us to bring out the good within us. Still, nowadays far too many people are caught, even trapped, in bad habits. So, I will focus on unhealthy habits – habits that may seem unbreakable – and analyze how we have the power to overcome such habits.

Most people who become addicted to undesirable habits such as smoking or drinking or taking drugs don’t start with the desire to become addicted. They simply want to enjoy, and feel that they can stop their indulgence whenever they choose to. What they don’t realize is that the decision is gradually taken out of their hands by that habit’s hard bindings.

The Bhagavad-gita (16.12) refers to desires as shackles and cautions that we are often bound by hundreds of such desireshackles. Whereas physical ropes make us motionless, the ropes of desires make us restless: these ropes make us run here, there and everywhere in pursuit of the promised pleasure. Because we retain the capacity to move about – and move about by desires that appear to be our own – we don’t realize that we are becoming bound. But each indulgence makes the rope thicker and tighter, thereby making the bondage harder – and harder to break free from.

When some such desireshackles become excessively strong and impel us towards dangerous and destructive actions, then we may try to resist their pull. And then we realize how alarmingly hard their bondage has become. The force of habits can make an insignificant indulgence seem irresistible.

A: Affliction

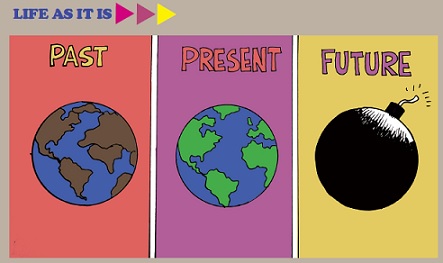

A great tragedy of contemporary life is that much of our misery is self-inflicted. Through the development of science and technology, we have sought to decrease many externally-imposed forms of misery. And yet we find ourselves afflicted by many selfinflicted forms of misery. Millions upon millions of people the world over are suffering from addictions, thereby subjecting themselves to self-destruction.

The phenomenon of selfdestruction is not unique to us humans. Fish charge to their destruction when they are captivated by baits, and mice rush to doom when captivated by cheese in mousetraps. Yet they have excuses – their lures look like food and they don’t know in advance that those lures are traps. Unfortunately, we humans don’t have either of those excuses. Cigarettes don’t look like food to anyone. And today who doesn’t know that cigarette smoking is injurious to health? We humans are supposed to be more intelligent than all other species – why then do we act more unintelligently than them?

B: Blitz

One reason for our alarming self-defeating behavior is external: we are impelled by outer influences, especially by the corporate-controlled media that bombards us with multitudes of advertisements.

Today when ads are so ubiquitous, we may not even realize that for thousands of years till some two hundred years ago, there existed practically no ads.

The insidious effect of ads is dissected insightfully by Oscar Wilde: “Fashion is a form of ugliness so intolerable that we have to change it every six months.” We all naturally desire to look attractive. But what is considered attractive is often determined by prevailing definitions of fashion. So, when a particular dress is deemed fashionable, we buy it, hoping to look good in it. But after a few months the corporate-controlled media deems some other dress fashionable. Then, we feel unattractive, ugly even, if we stick to the out-of-fashion dress.

Consider another example of the distorting power of the ad blitz. Cigarettes, for example, are advertised as cool. But how can something that burns be cool? The promotional slogan, “That’s cool” deserves the rebuttal, “I am not a fool.”

Because ads glamorize some products so aggressively and attractively, they erode our capacity for critical thinking. Thus, they impel us towards indulgence, even if such indulgence is self-destructive.

I: Introspection

When we end up under the force of habits doing things that we don’t want to do, we can either get frustrated with ourselves and beat ourselves up for our lack of intelligence or willpower. Or we can take that action as a spur for introspection: “If I do something that I don’t wish to do, I am either not the doer or not the wisher – there must be something inside me that is other than me, something that makes me do such things.”

What our introspection points to, Gita wisdom illuminates. It explains that our present existence is three-dimensional: we are not just physical creatures; our existence extends over the physical, mental and spiritual levels. Consider a computer system as a metaphor. It comprises hardware, software and user. The hardware is like our body; the software, like our mind; and the user, like the soul.

If the software of a computer gets infected with some malware, then it may open some sites even when we don’t want to open them. Normally, the software and hardware are meant to do what we want them to do, but malware in the software can make it do something else. And if we are not vigilant, we may get tempted by the site and start surfing it. If this happens repeatedly – the site opens repeatedly and we surf it – gradually that site may become one of our default sites, all the more so if the browser adeptly keeps track of our behavior and facilitates its repetition. Thus, we may end up hooked to sites that we initially had no intention of visiting.

If we are alert, however, we will recognize that we are being led towards sites that we don’t want to visit – and we will close those sites, and find some antimalware software to purge that misdirecting malware.

Introspection enables us to become similarly alert in our inner lives. Due to the blitz coming from the outer culture, certain desires pop into our consciousness and start prompting us to act out those desires.

If we naively accept those desires to be our own desires, we indulge in them, thereby getting fleeting titillation and lasting torment. Whenever we act out a desire, it becomes internalized as an impression in our mind. Over time, such impressions, when reinforced by repeated indulgence, become like default sites in our mental computer. Whenever we think of happiness, we immediately start thinking of that indulgence as the gateway to pleasure. Thus, the indulgence becomes a habit and eventually an addiction.

If, however, we are introspective, we can discern which desires are our own inner aspirations and which are external impositions.

Of course, introspection is just the beginning of the solution in the form of transformation just as accurate diagnosis is the beginning of the solution in the form of treatment.

T: Transformation

Transformation is not merely a matter of willpower just as curing a disease is not merely a matter of willpower. Willpower is no doubt required for curing a disease, but that willpower needs to be directed towards following the treatment process that will cure the disease. Similarly, for transforming our habits, we do need willpower, but that willpower needs to be directed towards following a process of inner reconceptualization. The reconceptualization centers on changing our conception or definition of happiness. As long as we, consciously or subconsciously, equate pleasure with indulgence in a particular habit, our efforts to change that habit will be sabotaged – inevitably. Such self-sabotage is inescapable because we are by our very nature pleasure-seeking beings. We can’t live without pleasure. So, if we hold on to the notion that giving up a habit means having to live without pleasure, we won’t be able to give it up, no matter how much we try.

Suppose we have a browser that tracks our private information, and we don’t want such information to be tracked. If that is the only browser on our device, it will open as soon as we click a link, even if we don’t want to use it for browsing. As long as it is the sole browser, we can’t avoid it. But it doesn’t have to be our sole browser; if we put in the little effort to install another browser that is more respectful of our privacy, then we can surf the net without the fear of being tracked. Just as we can find an alternative way to surf the Internet, we can find an alternative way to seek happiness. Such an alternative is provided by spirituality.

The Spiritual is Tangible and Irreducible

Nowadays, the word spiritual is used to refer to anything that makes us feel good. But the yoga tradition from India explains spiritual more precisely – it refers to the concrete higher reality that can make us feel good forever.

There is a core to our being that is non-material. The more neuroscientists probe the brain, the more they recognize that while consciousness correlates with changes in the brain, such correlations don’t explain the origin or nature of consciousness.

To understand how consciousness is irreducible, let’s consider two examples. Now, researchers can know when we are having dreams by putting appropriate sensors on our brain. Yet no matter how sophisticated these probes become and no matter how exhaustively they map the biochemical changes in the brain cells, they can’t tell us what the sleeping person is dreaming. To know the content of the dream, researchers will have to wake up that person and ask, “What were you dreaming?” This first-person experiential reality of consciousness is not reducible to the chemistry of the brain.

Similarly, suppose a reputed brain surgeon comes home from office and finds that his wife is upset with him. Will he say, “Let me do a scan of your brain to find out why you are upset.” If he does, his wife may well say, “You go and scan where you have lost your brain.” Brain scans can describe chemical changes that happen in our brain, including changes that happen when we experience some emotions. But understanding those chemicals and their changes doesn’t explain our first-person experience of the emotions themselves. Noble Laureate neuroscientist Sir John Eccles puts this understanding succinctly: “The brain is the messenger to consciousness.”

The Gita explains that this consciousness comes from an irreducible, immeasurable, infinitesimal spiritual particle known as the atma or the soul.

The soul is by nature sac-cidananda – it is eternal, conscious and joyful. As the soul is by nature joyful, it naturally seeks joy. When the soul’s consciousness is caught at the material level – as ours is at present – the soul seeks pleasure at the material level.

We Want more than what our Bodies Offer

Wherever we see consciousness, we can infer that the soul is present there. As animals too have consciousness, we can infer that they too have souls. The Bhagavad-gita explains that all living beings have souls that are essentially similar to our souls. The primary difference between humans and animals is that the soul has more developed consciousness in human forms than in animal forms.

Because of this developed consciousness, we crave for pleasure far more than animals do. Put another way, we want more pleasure than what our bodies offer us. That’s why we improve our eating by, say, preparing so many cuisines – we want more pleasure than what is available from the food provided in nature.

And that – our wanting more happiness than what is naturally available – is why we fall prey to bad habits. As long as we equate happiness with material happiness, we set ourselves up for frustration, be it in the form of general dissatisfaction or of a specific addiction.

So, we need to redefine happiness. Changing our definition of happiness means raising our consciousness to the spiritual level and finding happiness at that higher level of reality. Meditation has enabled millions all over the world and billions throughout history to find peace and joy. Meditation essentially means taking our consciousness from the changing material level of reality to the unchanging spiritual level of reality. Meditation becomes much easier when we center it on spiritual sound, using that sound as the concentration-point for our meditation. Such meditation on sound can be called sonic meditation. The yoga tradition explains that sonic meditation can be done most effectively by using special combinations of empowered spiritual sound vibrations. Such potent spiritual sound vibrations are known as mantras. The tradition gives us a wide array of mantras, but especially recommends one particular mantra as the most effective for our present times. This mantra is known as the Hare Krishna maha-mantra: Hare Krishna Hare Krishna Krishna Krishna Hare Hare // Hare Rama Hare Rama Rama Rama Hare Hare.

Spiritual sound acts as the elevator for our consciousness. If we place ourselves in an elevator, it automatically takes us up. Similarly, if we place our consciousness in spiritual sound – that is, we absorb ourselves in spiritual sound – we will find our consciousness rise to the spiritual level, and we will relish higher happiness that will decrease the pull of desires.

Such elevation of consciousness rejuvenates us and makes us better equipped to deal with all our life’s issues, including habits. By the inner peace and power coming from mantra meditation, we can make healthy choices in terms of curbing undesirable habits and cultivating desirable habits.

Our Spirituality Makes us Bigger than our Habits

As long as we think of ourselves as materialistic creatures, we reduce ourselves to becoming the puppets of our habits – whatever our hormones urge us to do, we have to do, because materialism would have us believe that we are nothing but our hormones, our chemicals. Albert Einstein was profoundly conflicted by the implications of the materialistic worldview. He had seen firsthand the atrocities committed by Nazis in Germany. Being a Jew, he had to flee from it by relocating to America. While he intuitively found the Nazi atrocities repugnant, he also recognized that a materialistic worldview implied that the Nazis couldn’t be blamed for their brutality – they were simply wired to act that way. Materialism, when taken to its logical end-point, deprives us of our free will and makes meaningless all notions of moral responsibility or legal culpability. More pertinently for our topic, if we swallow the notion that we have no free will, then it implies that we have no power to choose or change our habits.

Of course, we all know that we do have free will. Even atheists who write books saying that we don’t have free will want us to use our free will to read those books and thereby accept their belief system that we have no free will. Thus, in denying the reality of free will, they unwittingly acknowledge its reality.

Thus, while materialism makes us swallow the unbelievable and irresponsible that we have no free will, spirituality helps us understand our free will and maximize our freedom. Spirituality helps us realize that we are bigger than our habits. It explains that we are not programmed machines made of bio-chemicals – we are the operators of bodily machines. And these bodily machines are not just programmed, but also programmable. And we can reprogram our body-mind machine best by reconnecting with our spiritual essence. The more we redefine our conception of happiness, the more we can reprogram our psychophysical machine, thereby making it into an instrument for our growth and freedom.

So, the best means for transformation of our habits is the spiritualization of our consciousness, and the best means for spiritualizing our consciousness is meditation on spiritual sound.